Chartbook 226 Membership & Money: the Vilnius NATO summit & the looming impasse over Ukrainian membership in the Western alliances.

How do you manage the costs of security? Hard enough at any time to put a figure on it. The implications are even more daunting when a country like Ukraine is fighting for its survival.

This week at the summit in Vilnius, the question of Ukraine’s eventual membership in NATO comes to a head. The question is whether the possibility of Ukraine’s membership, first announced in 2008 in one of the last disruptive acts of the Bush administration, can be realized any time soon.

The US and Germany prefer a wait-and-see approach, conditional on the outcome of the war and Ukraine’s progress in meet membership criteria. They remain concerned about the possible reaction of Putin’s fragile regime to hasty moves to incorporate Ukraine. A roadmap for Ukrainian NATO membership would, after all, be the ultimate strategic defeat for the Kremlin. Washington and Berlin presumably believe that we should be sure that Russia is well and truly defeated before taking that step.

Ukraine and its most vociferous supporters argue that the West should not flinch before Russia’s nuclear blackmail. At the very least they want a statement that goes well beyond the 2008 language. Kyiv, through its extraordinarily successful public diplomacy, has acquired so much legitimacy that it has the power to considerably embarrass both Washington and Berlin over the issue.

The moral pressure being applied by its spokespeople in public and closed-door events in Europe this summer has been remarkable both in its vociferousness and lack of inhibition. Kyiv is all in. If it does not get some of what it wants from the Vilnius summit, one has to ask how it plans to manage the disappointment. If it is true that the West has repeatedly and irresponsibly led Ukraine down the primrose path, it is also true that influential segments of Ukrainian opinion tend to run down it.

The alternative to immediate membership or a precise roadmap to membership, seemingly preferred by both Berlin and Washington, are security assurances carefully distinguished from NATO and any Article 5 guarantee, but backed by specific commitments of military aid.

Shout out to the FT team of Henry Foy in Brussels, John Paul Rathbone in London and Felicia Schwartz who put together an excellent pre-summit report.

This choice sharpens to a point a basic and long-standing economic dilemma inherent in Western security strategy that already haunted NATO in the 1950s and 1960s in the debates over burden-sharing.

If Ukraine is granted membership in NATO, its costs of self-defense go down, as is true for all the other NATO members with the exception of the USA. You could say that Ukraine would get to join the other nations in free-riding on America’s awesome nuclear deterrent. You might also say that Ukraine’s membership would extend the benefit of the economies of scale provided by America’s nuclear umbrella. As we have seen in the case of Finland and Sweden (prospectively), the USA has more than enough deterrent capacity to extend a security guarantee to new countries, if it judges it prudent to do so.

The Biden administration is signaling that it is unwilling to bear the additional risks and costs to the US that an extension of Article 5 security guarantees to Ukraine would currently entail, or is likely to entail in the immediate future.

But the US is not indifferent to the fate of Ukraine. It is committed to ensuring that Ukraine does not lose the war and Washington wants to ensure Ukraine’s security in future. So, it is supporting Ukraine’s struggle for survival outside NATO. So far to the tune of $70 billon dollars. It goes without saying that that is a great deal more than the US has provided to any NATO member any time recently. And that is true even if we allow for America’s spending on European defense in general. It is certainly more than the US will hope to provide to Ukraine in future.

This sets up the dilemma. Whereas extending the NATO umbrella would provide Ukraine with existential security from the pooled resources of America’s existing arsenal, ensuring Ukraine’s future through military support outside NATO - the so-called Israel option - will entail an itemized bill for Ukraine military-support stretching into the indefinite future. A large part of that bill will have to be footed by the United States. And it is likely to be a lot larger than the bill it currently pays for Israel.

You might say that the choice is false. The NATO option would not really be cheaper, because if and when Ukraine joins NATO, the resulting impairment of relations with Russia will entail large extra expenses on conventional forces, to avoid having ever to trigger the nuclear deterrent. But Washington will no doubt push for those costs to be born by the Europeans themselves.

You might say that the choice is false because the “cost” of supporting Ukraine, as of supporting Israel and America’s other partners, is actually not a cost but a steady flow of lucrative contracts for America’s revived military-industrial complex. The money does not disappear in Ukraine but flows back to the US in weapons contracts. But even if this is the case, it still requires a reallocation of resources within the US that entails political choices. And Ukraine’s base of political support in the US is, one suspects, less deeply and less solid than that for Israel.

Looking beyond the immediate situation, there is thus a real dilemma here, both for the US and for its major European allies.

As they weigh the costs and risks of incorporating Ukraine into NATO and the available alternatives, they have to weigh escalation risk, but also long-run financial cost and the political sustainability of either security arrangement. Furthermore, this calculation is linked to, but contrasts with the question of Ukraine’s future EU membership.

EU and NATO memberships have historically been linked. The prevailing ideology in Brussels for a long-time denied this. But eforts by the EU to distance itself from this implied geopolitics have never rung less true than they do today, when the connection is as obvious as it was in 1950 at the time of the Korean war and the launching of the Coal and Steel Community.

Right now the connection it spoken out loud. The two memberships go together, the more urgent question is which order they come in. At the London Conference on Ukraine’s reconstruction this summer, amongst senior Ukrainian and Western figures, there was unanimity that security whether by NATO or other means came first and reconstruction and prospective EU membership came second. Whether one can really imagine Ukraine as a full EU member but not a NATO member is a conundrum.

And this is significant because the financial logic of EU and NATO membership is different.

The ultimate guarantee of security provided by NATO lies in benefiting from the US nuclear deterrent, which offers economies of scale, meaning that supporting Ukraine outside NATO is less risky but more expensive. The same is not true for EU membership. There are shared benefits - “economies of scale” in the broadest sense - from expanding the EU. But, in financial terms EU-spending on new members surges after their accession. It was that pattern that marked the arduous path traversed by the new East European members in the 1990s before they began benefiting following accession in the 2000s from large-scale transfers. No country has benefited more than Poland, to which Ukraine is frequently compared.

Right now the EU’s support for Ukraine is already substantial. But all available estimates suggest that it will be dwarfed by the commitments necessary after an eventual Ukraine accession. Those are expected to run into the hundreds of billions whether in direct grants or de-risking of private lending.

Optimists declare that Ukraine’s incorporation should not be seen as a cost. It will be a boon for the EU, bringing new talent and new resources, unleashing a giant investment boom and stimulating green growth. This is the equivalent of the “Keynesian”, military-industrial complex argument for military assistance to Ukraine. In devoting money to structural adjustment and convergence in Ukraine, the EU is spending money “on itself”. The funds will flow back to contractors in the rest of the EU.

This makes sense as a macroeconomic analysis, but like the military-industrial-complex argument, it downplays the distributional issues, which are far more dramatic in the case of Ukraine’s eventual EU membership. By most calculations, an eventual Ukrainian membership will fundamentally reshuffle the EU’s budget. And no country will more seriously affected by this than Poland, which is decisive for Europe’s relations to Ukraine and also for NATO’s strategy in Eastern Europe. In its boycott of Ukraine’s wheat exports Poland has given notice of how aggressively it will defend its sectional economic interests in any commercial dealings with Ukraine. That is Poland’s current government at least.

If we assemble the pieces of this jigsaw puzzle, it suggests not so much a roadmap for Ukraine’s future and its relations with the West, but an impasse.

NATO membership or at least security must come before EU membership and large-scale reconstruction. On financial and political grounds, the EU has every reason to defer Ukrainian membership for as long as possible. On security grounds the US (and Berlin) prefers to defer NATO membership until a (much) later date, until the war is decided in Ukraine’s favor. Instead of NATO membership, they will offer security commitments. But these will entail large amounts of military support, which requires regular and explicit approval by an unstable American Congress. Europe can provide financial assistance, but lacks the means to meet Ukraine’s security needs. This jigsaw is missing some pieces before it assembles into a satisfactory picture.

Expect the NATO summit to be awash with promises of weapons for Ukraine. The German government is already today trailing possible new packages.

But when you read the numbers that emerge from the summit, place them against the structural impasse sketched above. They are part of a double calculation - by the key players in NATO and the EU - which is not designed to give Ukraine what it wants any time soon.

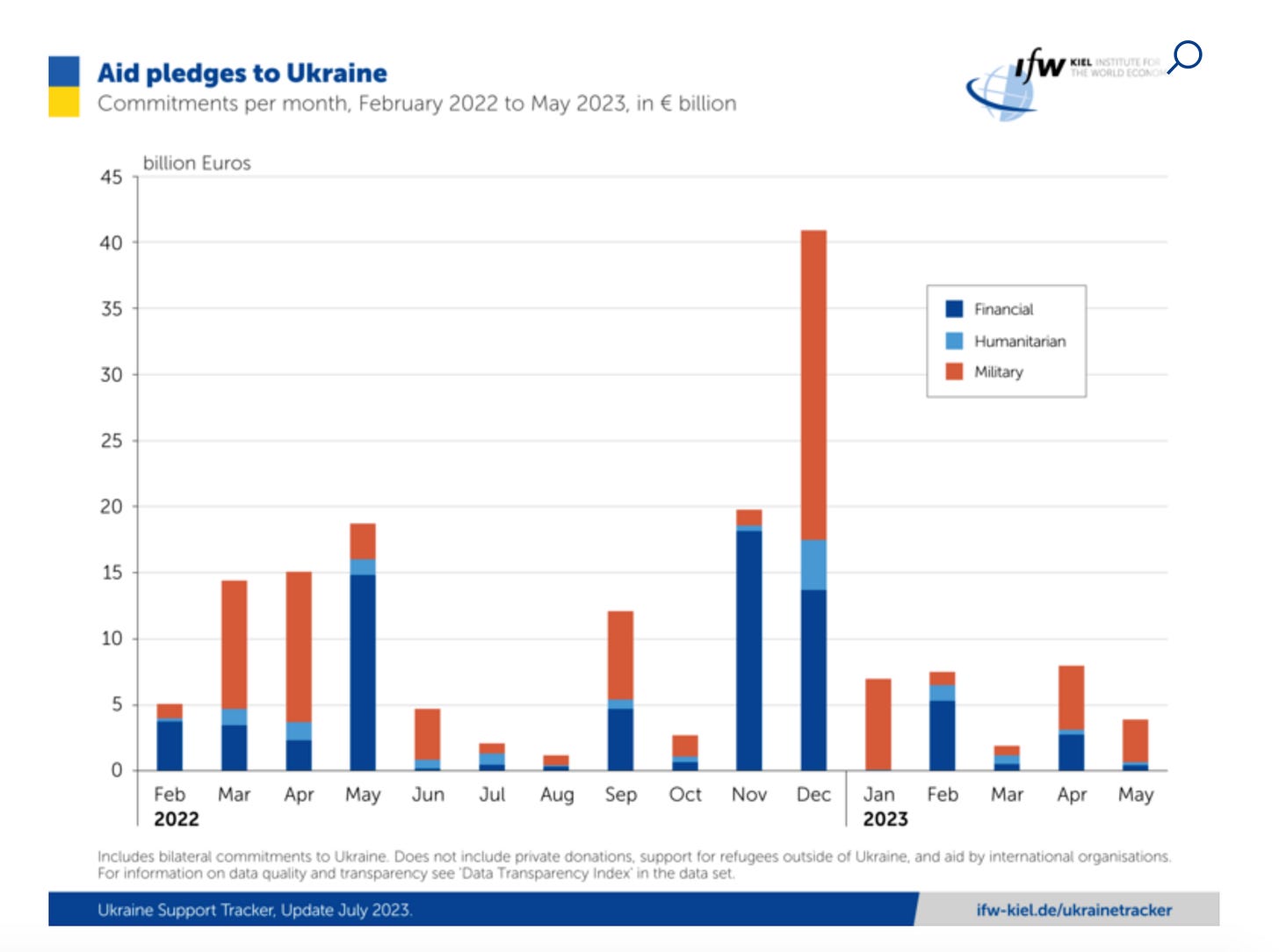

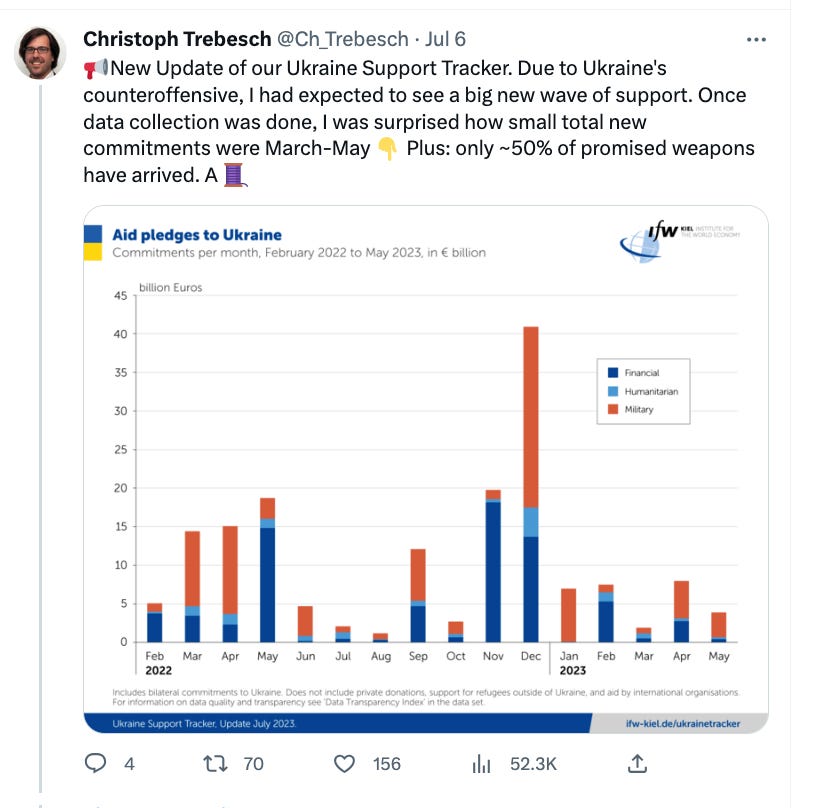

And place the numbers that emerge from the summit, also against the stuttering flow of new aid commitments to Ukraine since the start of the year. The figures compiled in the latest issue of the Kiel-tracker show how little new commitments there have been to Ukraine in 2023 so far.

As Christoph Trebsch the lead researcher on the project notes - he is and one of the most consistently productive empirical economists out there right now - the numbers run counter to prevailing narratives.

Furthermore, what Ukraine needs is not just immediate help but a stable outlook for the immediate future.

Tellingly, whereas the EU on June 20 proposed a 50 billion euro framework to cover recovery, reconstruction and modernisation for the period 2024-27, which can presumably be used to help finance the survival of Ukraine’s war economy, the US has hitherto been silent on the issue. Biden’s budget published in March included only $6 billion in itemized assistance for Ukraine and Kyiv has noticed:

Serhiy Marchenko, Ukrainian finance minister, told the Financial Times it was a “good signal for all other G7 nations that the EU has already stepped in”. “What is your position? Where is your support?” he asked of other allies.

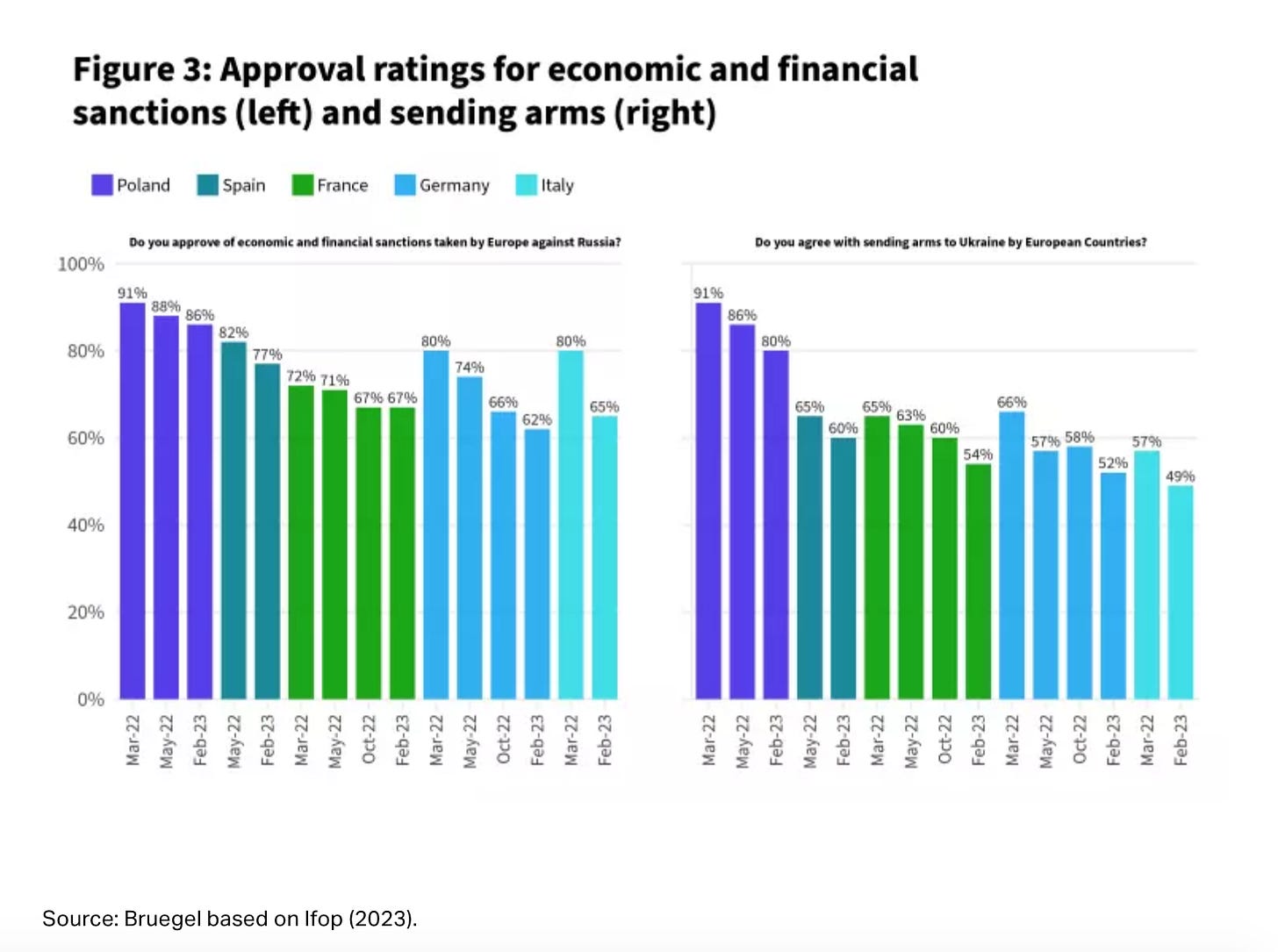

If that is a matter of political calculation the answer may be found in the polling. In the Europe there is a marked difference between Northern and North-East Europe (hawkish), Western Europe (wait and see) and Southern and South-East Europe (neutralist), but the levels of support remain relatively steady.

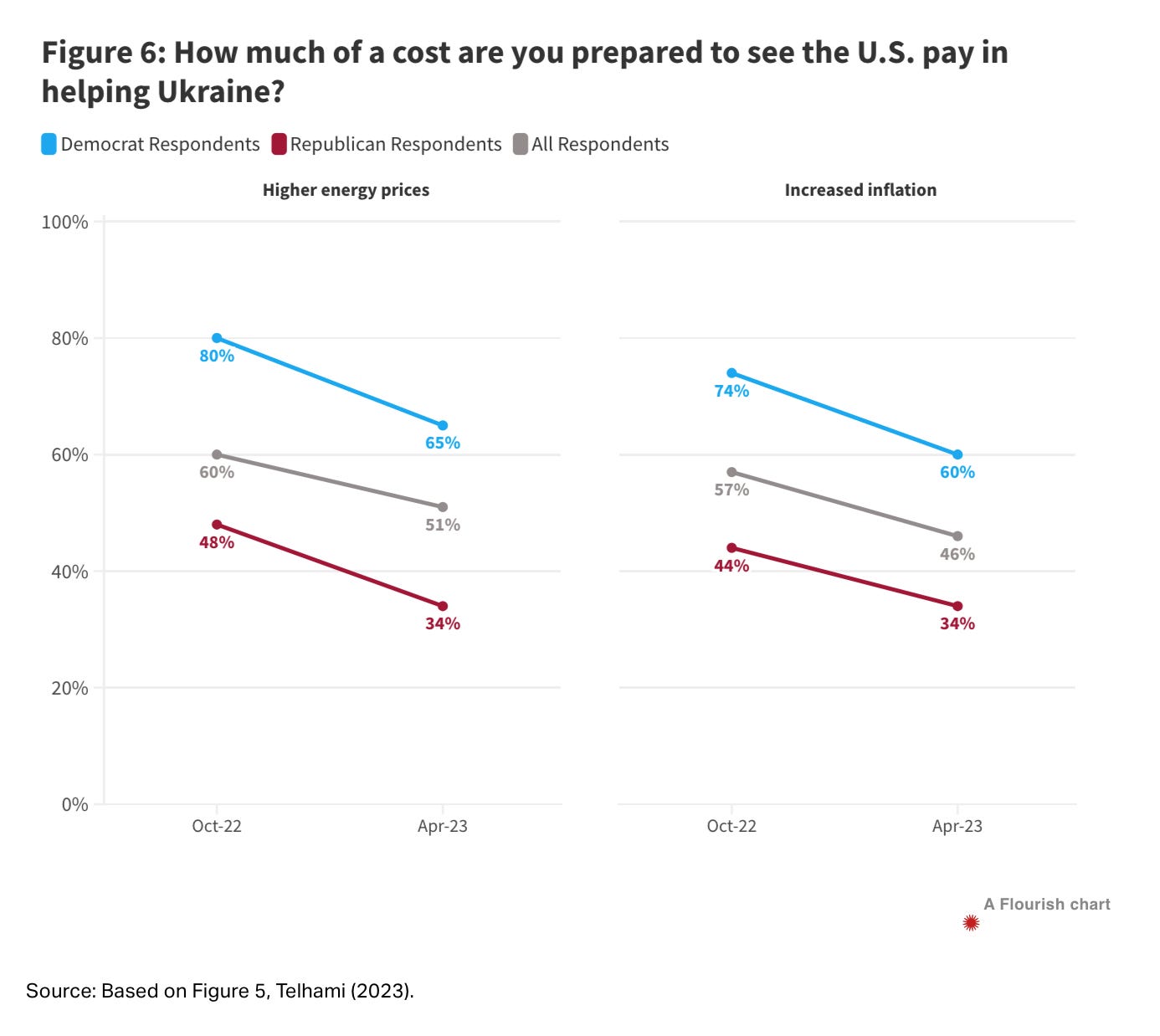

As this excellent Bruegel report by Maria Demertzis Camille Grand Luca Léry Moffat notes, the situation in the United States and, from Ukraine’s point of view, headed in the wrong direction.

As Shibley Telhami of Brookings notes, only a minority of Americans (38 percent) back their government in supporting Ukraine for as long as it takes to secure victory. And yet it is precisely that which the Biden team will likely offer Ukraine as compensation for blocking any move towards NATO membership. It is probably the best that can be done under the circumstances from the point of view of Berlin and Washington. But it is a recipe for crises to come, a risk to which Europe and Berlin should be particularly attentive.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

"Furthermore, what Ukraine needs is not just immediate help but a stable outlook for the immediate future."

What Ukraine needs is negotiations, and the United States to stop sabotaging peace efforts.

Some points:

1. No evidence of fragile Putin "regime". Mr. Tooze, do you think Russians have not accumulated from 2000 onwards enough evidence to support Mr. Putin as their president? If anything, Russians want a ramp up effort to deal and finish Ukraine.

2. No evidence of Ukraine diplomatic success outside EU, US, and US protectorates like Australia, Japan, S. Korea. CELAC countries have even refused to include the mention of Ukraine in their joint statement with EU, claiming that Ukraine is a European problem.

3. What do you think is the price for security the Russians are willing to pay, given the scenario in the books prepared by the Americans immediately after the dissolution of USSR?

https://www.thepostil.com/1993-the-barry-r-posen-plan-for-war-on-russia-via-zombie-state-ukraine/