President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is no friend of Sweden. But a Swedish economist may hold the key to understanding the inflation that Erdogan has unleashed.

What is next for Turkey?

Do Erdogan’s ideas make sense on their own terms?

Has Turkey emerged as a Middle Eastern power?

How can Turkey's current economic dilemmas ever get resolved?

Those are a few of the questions that came up in my conversation with Cameron Abadi on our FP podcast Ones and Tooze. You can listen and read more here.

***

It is tempting, when you look at Erdogan’s track record to talk about a pattern of resilience. He has pulled a lot of “rabbits out of the hat”. But the more closely you look at Turkey’s macroeconomic data today, the more you realize the singularity of the current situation. To escape his current predicament Erdogan needs to perform no ordinary conjuring trick.

Though there is a lot of focus on the external value of the lira, Turkey fx reserves etc, the dominating factor in Turkey’s political economy right now is the inflation rate.

In recent years Turkey has not been what you would call a low-inflation country, but the acceleration of inflation since the autumn of 2021 has been spectacular. Since September 2021 the price level has more than doubled.

Source: Trading Economics

In the financial crisis of 2018 as well, there was an acceleration of inflation, but as one can see from the price level graph that proved short-lived. This time, extremely elevated inflation has persisted for more than 18 months and has changed every aspect of socio-economic life.

Though the rate of increase has come down somewhat since November 2022, prices continue to rise at an annualized rate of between 40 and 50 percent. There is no guarantee that the deceleration will persist. Inflation expectations are unmoored. And there is widespread suspicion that the official numbers understate an inflation rate that according to independent experts is actually closer to 100 than to 50 percent.

Inflation has been a common experience around the world since 2021, but there isn’t much doubt about what has caused Turkey’s dramatic inflationary surge: The singular economic policies of Erdogan’s regime.

Erdogan is notorious for advocating low interest rates. But what is commented on less frequently is the strangely lop-sided quality of his monetary radicalism. Erdogan’s advocacy of cheap credit is not complemented, as one might expect in a true populism, with an equally open-handed approach to fiscal policy. The result is that Turkey, at least as far as one can judge from macroeconomic variables, is suffering a rather peculiar inflation shock driven by a huge surge in private credit, enabled by low interest rates, rather than fiscal incontinence.

I must admit that I feel somewhat tentative venturing this reading. I haven’t seen the “private credit” dimension highlighted elsewhere in precisely these terms. After all the ultimate source is clearly a political decision. But this seems to be what the data show: Turkey is in the grips of an extreme case of Wicksellian inflation.

Johan Gustaf Knut Wicksell (December 20, 1851 – May 3, 1926) was a leading Swedish economist of the Stockholm school. He is known for his analysis of inflationary processes as driven by the endogenous creation of credit in reaction to interest rates that are below what he termed the natural or equilibrium rate. Many regard Wicksell as the grand-daddy of modern-day inflation targeting.

***

Focusing on the monetary expansion is not to deny that in Turkey’s inflation, as elsewhere in the rest of the world, cost-push and “real” factors are at work.

Turkey suffered from the dislocation of COVID and supply chains as much as any Emerging Market. It is particularly sensitive to the impact of rising global energy prices as it is highly dependent on imported energy. The combination of a strong dollar and high energy prices hits Turkey hard.

But Turkey’s predicament is not generic. The problem is that the lira has depreciated more strongly than any other currency in the world. This is explained by the interaction between fx markets and domestic monetary conditions.

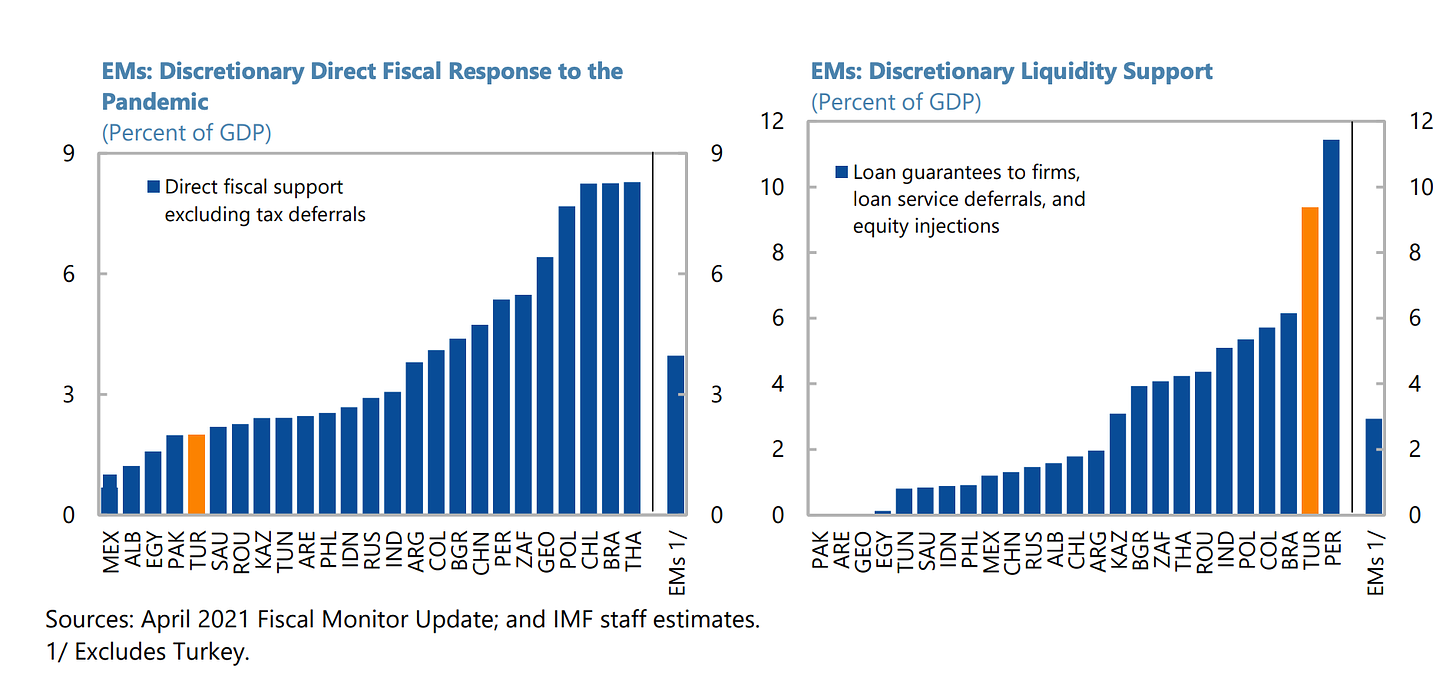

The dramatic loosening of credit conditions in Turkey began during the COVID crisis. Already in 2020 Turkey was exceptional for a combination of exceptionally generous credit and loan support and relatively tight-fisted fiscal policy.

Source: IMF

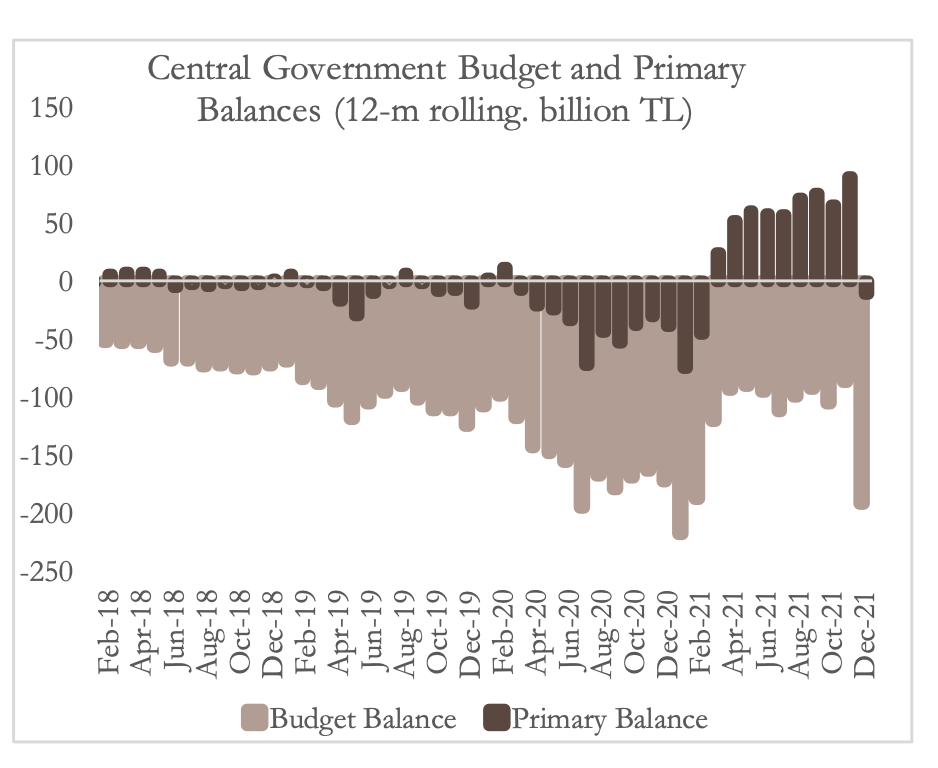

This contrast between policies continued in the aftermath of the pandemic. In 2021, as Turkey approached the tipping point to a sudden acceleration of inflation in the autumn, fiscal policy was on a tightening path. The primary deficit was closing.

Source: World Bank

Maintaining a tough fiscal stance in the face of an inflation is not easy, especially since Erdogan’s government has used tax relief as a way to cushion the impact of inflation on the population. Furthermore, Ankara’s fiscal situation is put under further pressure by the fact that a large share of its relatively small public debt is denominated in foreign currency meaning that the lira debt burden rises as the currency depreciates.

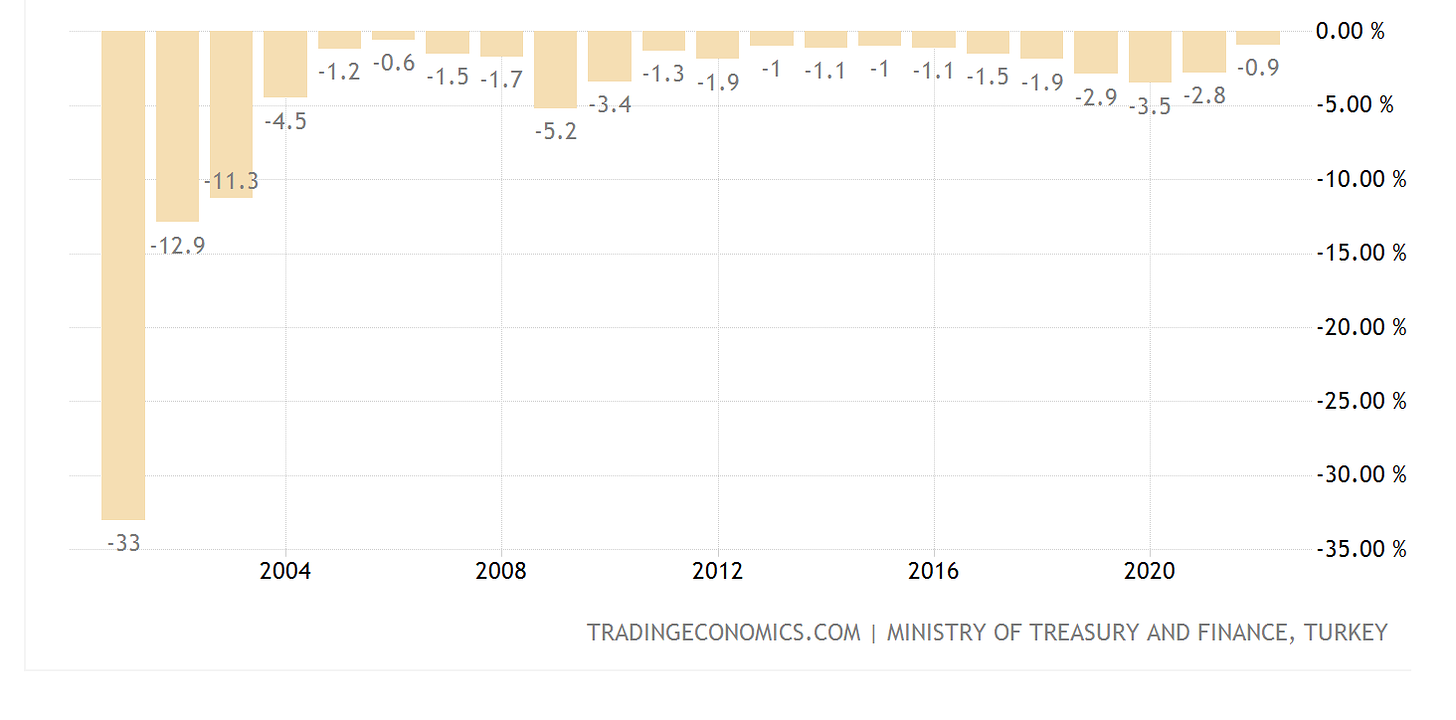

Nevertheless, after a brief deviation from the tightening course over the winter of 2021-22, Turkey’s deficit continued to tighten in 2022.

Turkey’s fiscal deficit as share of GDP.

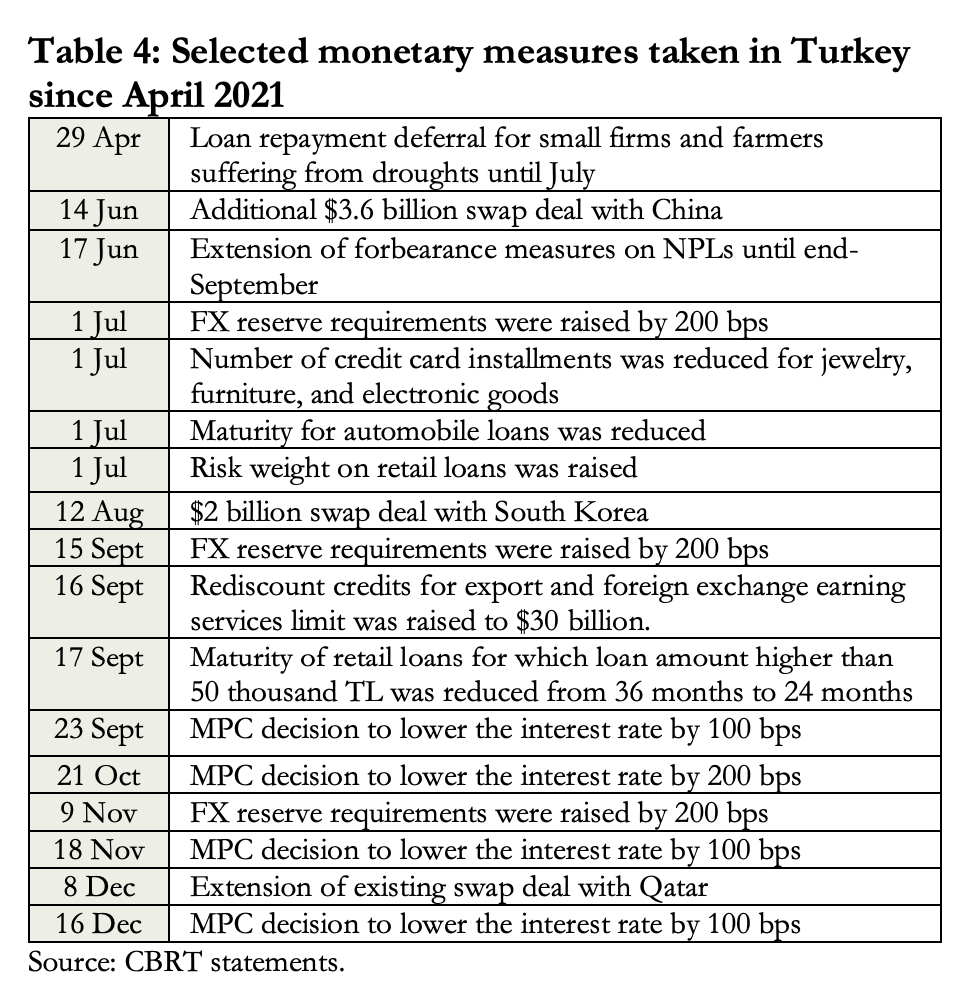

In light of the tight fiscal stance, there can be little doubt that what triggered the inflationary surge in the autumn of 2021, were a series of decisions on monetary policy. In the face of a global interest rate surge, the central bank of Turkey under the thumb of President Erdogan, slashed rates.

Source: World Bank

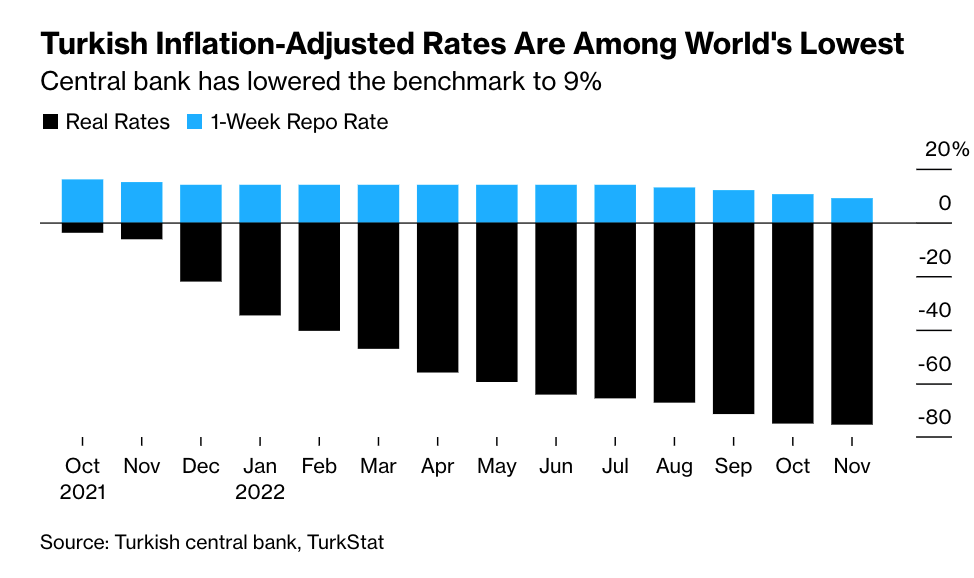

By December 2021 Turkey’s inflation-adjusted real interest rates were falling deep into negative territory.

Source: Bloomberg

You do not have to be a true-blue Wicksellian and a devout believer in the idea of an equilibrium, “natural” rate of interest - I am certainly not - to agree that real interest as low as those in Turkey must be a source of powerful, dynamic disturbance.

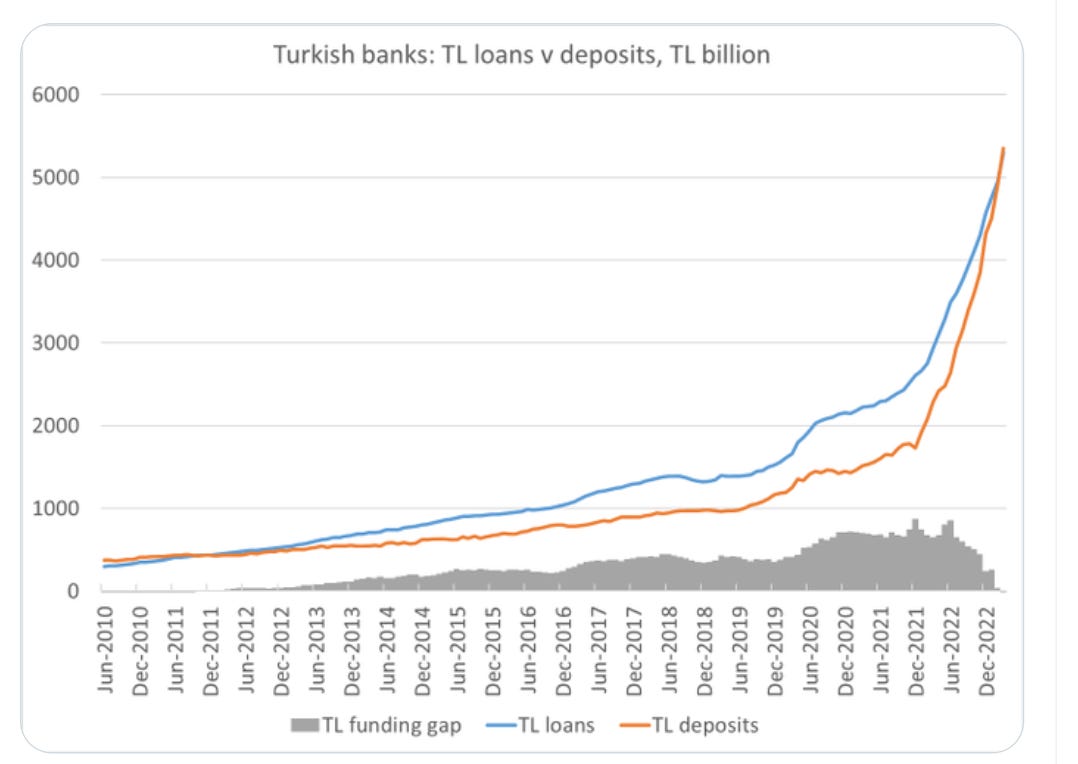

In response to this huge incentive to borrow, as this graph by Brad Setser shows, bank lending and borrowing took off and with them aggregate demand.

One set of prices that immediately surged in response to the credit boom was real estate. Housing became extremely attractive as an inflation hedge, driving a surge in prices in real as well as nominal terms.

Source: World Bank

In an inflationary boom of this kind, the struggle for advantage is over the allocation of credit and this became a central arena of policy in Turkey in 2022.

Regulators are forcing commercial lenders to prioritize exporters and smaller businesses that count for nearly three-quarters of the job market. …New lira loans for smaller firms -- a key group targeted for credit growth -- rose nearly 10-fold on an annual basis during the first 10 months of this year, compared to a seven-fold increase for large corporates … “Erdogan learned from the experiences of 2018 and 2020,” when explosion in loans boosted imports, inflation and eventually resulted in a weaker currency, said Nick Stadtmiller, emerging markets director at Medley Global Advisors in New York. …. Businesses that don’t fit the government’s image of worthy borrowers, including those rich in foreign currency, are struggling to secure cheap credit, even as rates were slashed to 9% on Thursday despite inflation at 85%. …. Banks can either offer cheap loans to high-priority clients or lend at higher costs to others. The latter, though, requires them to buy a large amount of government debt to be parked at the central bank. That leaves little incentive to lend to second-tier clients. …. “Only exporters with little import needs can get loans, which is only a handful of people,” said Eren Gonul, a sales manager at an Ankara-based furniture maker.

Credit expansions are monetary events, but they are rarely, if ever, purely monetary events. They generally reallocate the balance of credit between sectors and thus also the access to real resources. In favoring small and medium-sized firms Erdogan is, as ever, attentive to his popular base. In political and economic terms, the effects of the current inflationary surge will outlast the eventual stabilization.

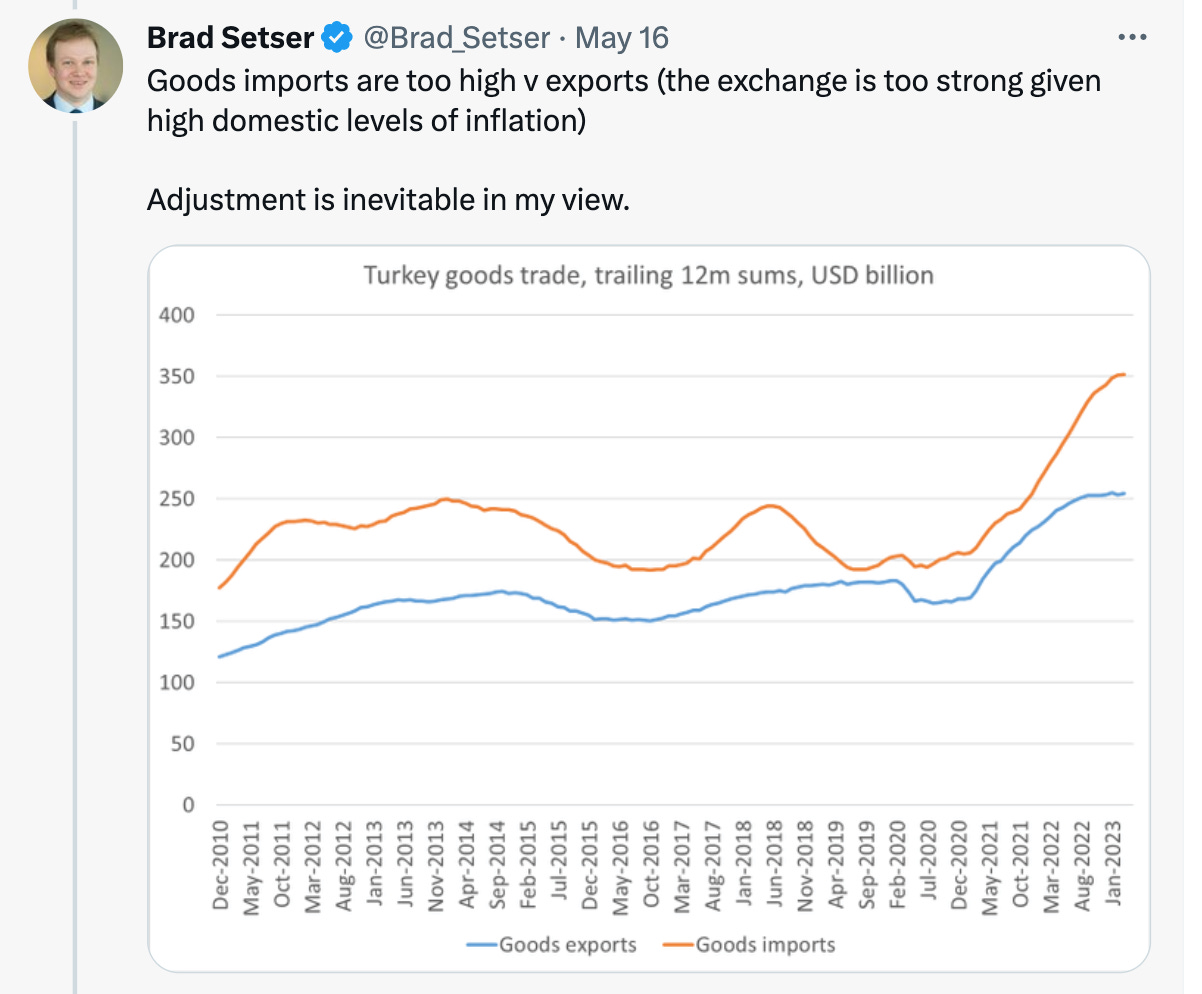

One such effect comes through the foreign account. As inflation accelerated, the external value of the lira depreciated, but not enough to match the domestic price surge. So the net effect is that the lira is overvalued. Exporters have struggled whereas imported goods became relatively cheaper in lira-terms.

***

In 2023, the central question is how long this unbalanced policy-mix and the inflationary reallocation of real resources can continue.

The devastating earthquakes that hit South Eastern Turkey and Syria in February 2023 demand a reconstruction drive that is costed at more than 100 billion euros. This will require more than private credit to fix.

And the impact of elevated inflation on society at large is painful. Turkey is not Argentina, which is well-habituated to rapid inflation. Those who gain access to credit and can adjust their prices and wages do well. But large segments of Turkish society are suffering.

Lower-income Turks have experienced huge falls in real income. Poverty rates are rising fast. And workers as a whole have been impacted severely.

As of the third quarter, unit labor cost decreased to -23.2 percent which is the lowest of the last 12 years. The sharp decline in this indicator reflects the erosion in the purchasing power of workers and the contraction in the share of labor payments in national income with the rapidly increasing inflation

Source: TEPAV

The minimum wage set at the end of 2022, with Erdogan’s personal imprimature, was increased by only 54.7 percent to 8,506 Turkish liras (US$455). As the WSWS reports, this is “barely above the hunger limit of 7,786 liras for a family of four calculated by the Türk-İş confederation at the end of November and well below the poverty line of 25,364 liras.”

***

Pre-election coverage of Turkey suggested that Erdogan’s inflation would be his downfall. He had ruptured the authoritarian bargain that has sustained him in power. He would be ousted at the ballot box and it would up to the opposition to face the challenge of stabilization. They duly prepared a economic program. As if to confirm Erdogan’s accusations against the “interest rate lobby”, Western money managers like Citi group and Vanguard promised that tens of billions would flow into Turkish bonds if only Erdogan lost.

That now seems moot. Erdogan and his hand-picked team will likely rule on. If this is the case, how long will they continue the current unbalanced policy?

The most immediate constraint may turn out to be financial rather than socio-political.

The central bank, which Erdogan has reduced to his willing tool, has resorted to all sorts of makeshift to finance the deficits. But by the spring of 2023 central bank reserves are generally reckoned to have reached critically low levels. In the foreign exchange markets the lira was plunging and demand for gold surging.

At some point Turkey will no longer be able to roll over its foreign debts and will face a sudden financing stop. At that point, if the monetary diagnosis of Turkey’s imbalances is correct, Erdogan’s regime has one advantage.

An inflation driven by a private credit boom unleashed by willfully low interest rates is presumably much easier for the state to stop than one which is driven first and foremost by the unbalanced political economy of the state itself i.e. by a public budget in giant deficit. In the Turkish case, the discrepancy between monetary and fiscal policy is so stark that there is scope for off-setting a tightening of monetary policy and a further devaluation of the lira with a more open-handed fiscal policy, focused on the needs of millions of low-income households and reconstruction in the earthquake zone.

What new iteration of Erdoganism will emerge, we do not yet know. But both the international and domestic limits of the current inflationary process leave little doubt that it is not a matter of if, but when.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you wil receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Fascinating stuff. One question: The 2022 minimum wage is equivalent to $455 per ... what? year? month? week?

I spent some of my morning reading today’s Chartbook 215. I have absolutely no background in economics but thanks to Duck Duck Go was able to look up so many terms and learn so damn much. Old dogs can’t learn new tricks but I’m happy at least to now have a fingernail’s grasp on a subject that has always seemed beyond my comprehension and thus have not been not interested. And all for the price of a subscription. Money well-spent.