“What is history for?” … “It makes us brave!”

I’ll never forget this response by my distinguished colleague Professor Jonathan Riley-Smith to one of the “theory and practice” questions with which we used to torture Cambridge undergraduates back in the 1990s and early 2000s. Riley-Smith’s answer resonated with me, precisely for its profound, almost archaic quality:

History as consolation and spur, as inspiring legend. History as conducive to a life lived in the spirit of of bold action. History as one of the places where we preserve tales of valor and the memory of heroes. History as a form of resistance against the oblivion to which power may wish to consign those who oppose it.

Riley-Smith’s exclamation came to my mind this morning in light of the conspicuous show of courage by Russian opposition politician Vladimir Kara-Murza in the face of the Moscow City Court. Since the early 2000s Kara-Murza has been a thorn in the side of Putin’s regime. Having survived two poison attacks in 2015 and 2017, in 2022 he spoke out against the war, was arrested, charged and has been put on trial in the Moscow City Court. On trumped-up charges the prosecutors are demanding a 25-year sentence in a brutal, “strict regime” prison colony.

In the procedures of the Russian judiciary, before judgement and sentencing the accused are afforded the chance to make a final statement. I reproduce below Kara-Murza’s speech from the Washington Post, for which he has been a regular writer. The speech is a monument to the articulation of courage and the historical imagination:

MOSCOW CITY COURT — Members of the court: I was sure, after two decades spent in Russian politics, after all that I have seen and experienced, that nothing can surprise me anymore. I must admit that I was wrong. I’ve been surprised by the extent to which my trial, in its secrecy and its contempt for legal norms, has surpassed even the “trials” of Soviet dissidents in the 1960s and ’70s. And that’s not even to mention the harshness of the sentence requested by the prosecution or the talk of “enemies of the state.” In this respect, we’ve gone beyond the 1970s — all the way back to the 1930s. For me, as a historian, this is an occasion for reflection.

At one point during my testimony, the presiding judge reminded me that one of the extenuating circumstances was “remorse for what [the accused] has done.” And although there is little that’s amusing about my present situation, I could not help smiling: The criminal, of course, must repent of his deeds. I’m in jail for my political views. For speaking out against the war in Ukraine. For many years of struggle against Vladimir Putin’s dictatorship. For facilitating the adoption of personal international sanctions under the Magnitsky Act against human rights violators.

Not only do I not repent of any of this, I am proud of it. I am proud that Boris Nemtsov brought me into politics. And I hope that he is not ashamed of me. I subscribe to every word that I have spoken and every word of which I have been accused by this court. I blame myself for only one thing: that over the years of my political activity I have not managed to convince enough of my compatriots and enough politicians in the democratic countries of the danger that the current regime in the Kremlin poses for Russia and for the world. Today this is obvious to everyone, but at a terrible price — the price of war.

In their last statements to the court, defendants usually ask for an acquittal. For a person who has not committed any crimes, acquittal would be the only fair verdict. But I do not ask this court for anything. I know the verdict. I knew it a year ago when I saw people in black uniforms and black masks running after my car in the rearview mirror. Such is the price for speaking up in Russia today.

But I also know that the day will come when the darkness over our country will dissipate. When black will be called black and white will be called white; when at the official level it will be recognized that two times two is still four; when a war will be called a war, and a usurper a usurper; and when those who kindled and unleashed this war, rather than those who tried to stop it, will be recognized as criminals.

This day will come as inevitably as spring follows even the coldest winter. And then our society will open its eyes and be horrified by what terrible crimes were committed on its behalf. From this realization, from this reflection, the long, difficult but vital path toward the recovery and restoration of Russia, its return to the community of civilized countries, will begin.

Even today, even in the darkness surrounding us, even sitting in this cage, I love my country and believe in our people. I believe that we can walk this path.

Given the terrible ordeal that Kara-Murza faces, the resources of courage, conviction and determination that he must have summoned to make this statement, defy comprehension. He knows that Putin’s regime will bury him alive and yet he refuses to flinch.

But what stopped me dead in my tracks was that phrase in the final line of the opening paragraph.

“For me, as a historian, this is an occasion for reflection.”

Drawing himself up to face his terrible fate, he draws strength from his self-description “as a historian”, strength to withstand the immediate pressure of the situation and to carry on thinking. Rather than sinking into an abyss, it is as if, assuming the historian’s mantle, he can soar out of the cage in which he is being held. He can look back through time and weigh the scale of the abuse to which he is being subjected and the shame it brings on Russia, but also to look to the future, to a moment of day-break, towards a spring that will inevitably come. Historical consciousness is a source of courage.

As a historian myself, who often asks the question - why? and what for? - Kara-Murza’s speech moved me deeply. All the more so, because I was one of the people - one of a team at Cambridge - who helped to give him the identity that at this terrible moment he chose to adopt, that of a historian.

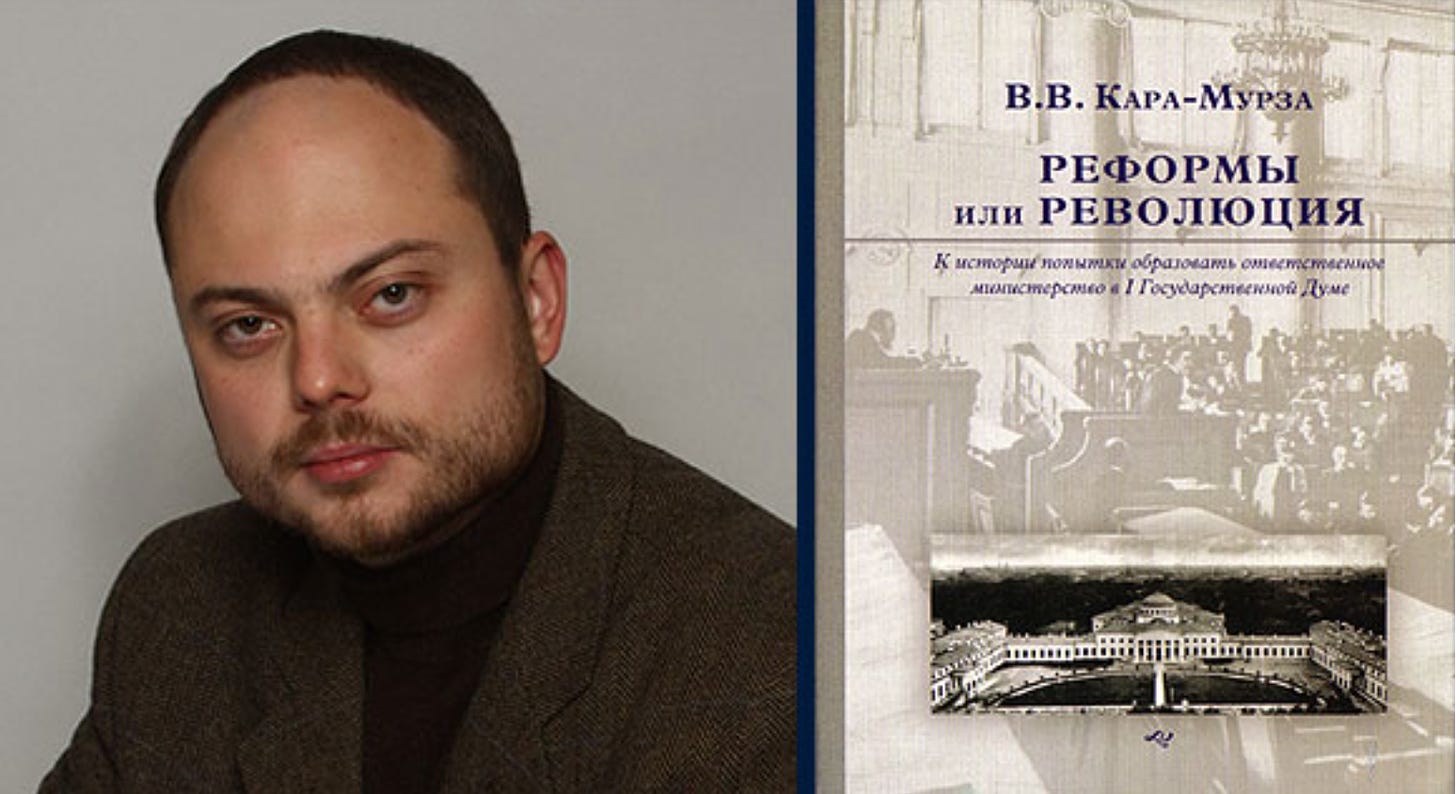

At Cambridge, early on in his undergraduate career, perhaps in 1998 or 1999, I was Kara-Murza’s teacher. In the Cambridge system this means that over a period of two months we met for many hours, one-on-one, to discuss history, including, if memory serves, Russian history. I do not follow Russian oppositional politics, so it is striking to me that amongst the hundreds of students I taught in that period I remember him so vividly, his energy, the force of his personality, the depth of his historical knowledge that in 2011 would lead to the publication of his historical study of the Cadet party and their failed effort to build constitutional government in Russia in 1906. Alongside his journalism and activism. Kara-Murza truly is a historian.

All of this came rushing back to me when I first heard news of his arrest in early 2022. A series of vivid images of the two of us sitting, quite close together, debating one of his essays. It was a memory, I should say, accompanied by a feeling of guilt. The sense that perhaps in the years afterwards I had neglected this remarkable person. I fear there were emails, many years ago, perhaps to do with his book, unanswered by me. But that is for me and my conscience. I mention it only to ward off even the suggestion of reflected glory. I deserve none. When we started talking, when he was a student in his late teens, he already carried within him a sense of historical motivation which, I now realize, was more intense, more demanding, more self-sacrificing than I will ever bear.

Today I want simply to bring Kara-Murza’s case to your attention, to express the humility I feel in the face of his magnificent sense of historical purpose and to ask you to join me in paying our respects to his extraordinary courage.