Chartbook #202 What went wrong at Credit Suisse? The Swiss roots of the debacle.

The crisis at Credit Suisse this week was triggered by the global anxiety about banking stocks unleashed by the mini-wave of US bank failures. The panic is reflected in the surging price of credit default swaps on Credit Suisse debt.

Source: FT

The problems at CS go back further than that, of course.

The bank had come through the 2008 crisis relatively better than its great Swiss rival, UBS. Whereas UBS needed full-scale state intervention, Credit Suisse managed to rely on capital injections from the Gulf and dollar liquidity from the Fed, both directly in New York and via the swap lines and the Swiss National Bank. Arguably, according to Tobias Straumann the preeminent historian of Swiss banking, this led Credit Suisse to get sloppy.

Following a series of scandals in 2021 CS stock market valuation parted company from that of the rest of European banking and UBS.

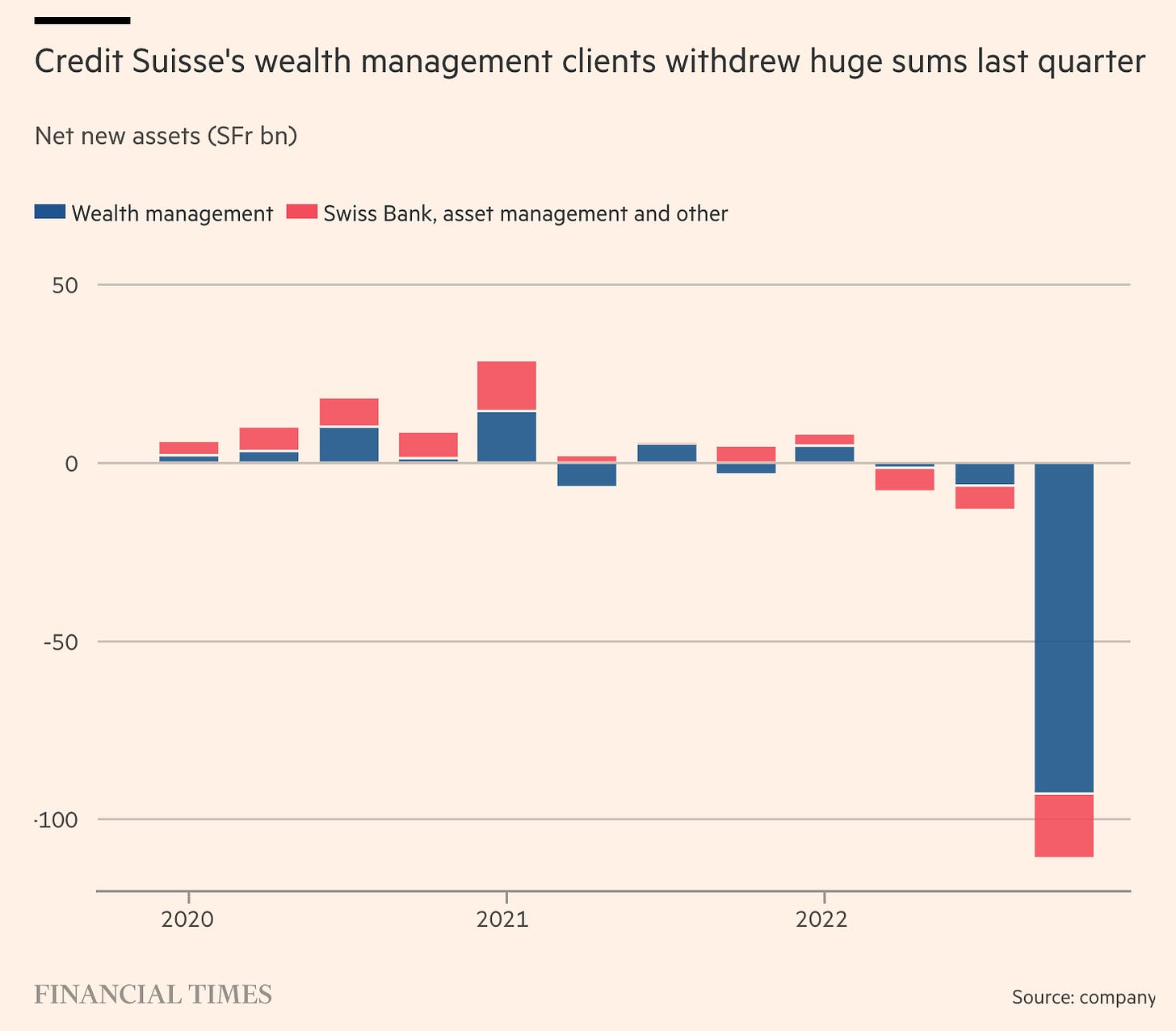

Tidjane Thiam as CEO wanted to spin off the domestic universal bank as a separate Swiss operation. But he was ousted under scandalous circumstances. In 2022 wealth management clients began losing patience with the bank and by the end of the year a steady trickle of withdrawals suddenly became a flood.

It was this precarious situation which made the tremors coming from across the Atlantic so dangerous for Credit Suisse.

Seen in this light the crisis is the result of the intersection of US turmoil with corporate mismanagement. But what led CS into such trouble? As Straumann points out in his NZZ interview, the Credit Suisse debacle is best seen as the latest phase in the crisis-ridden effort by Zurich’s liberal Protestant elite (Freisinn) to build corporate champions of global scale on the basis of the incestuous networked politics of Switzerland.

The world got to know Swiss chocolate giants, pharmaceutical, insurance and banking giants but behind them stood tight local networks. At home this elites political wing was the FDP party, one of the perpetual parties of power in Switzerland’s conservative democracy.

Freisinn’s business networks centered around figures like Rainer Gut who launched Credit Suisse on its globalization drive in the 1980s, helped to create the ill-fated Swissair conglomerate and also sat on the supervisory board of Nestlé (not itself Zurich-based).

Swissair failed in the aftermath of the 2001 grounding. And Credit Suisse too was in serious trouble in the early 2000s. Gut’s role was later taken by Walter Kielholz who linked Credit Suisse to Swiss Re the reinsurance giant and functioned as one of the great patrons of the arts in Zurich.

It is the hubris of this network of influence, seeking to combine a domestic Swiss universal bank, a global wealth management operation and a US-style investment banking arm, which ultimately led Credit Suisse into its current dire straits. It is also those connections however that ensured that it would never be allowed to fail.

Corporate leadership and the Swiss state nows faces tough choices. Hitherto the Swiss state has cleaved to a two bank model, maintaining both UBS and Credit Suisse as rivals. Whether that is tenable remains to be seen. The most obvious candidate to take over Credit Suisse is UBS, but as Owen Walker reports

Last month a person involved in UBS’s war-gaming told the FT that the bank remained on alert for a “999” emergency rescue call from the Swiss government. “The country is committed to a two-bank model, but we would be naive not to prepare for it,” they said. Under the scenario presented by Abouhossein, if UBS did take on the business, it would IPO Credit Suisse’s Swiss business, wind down the investment bank and retain the wealth and asset management arms. But for executives at UBS, who are focusing on growing the group’s US wealth business and catching up with Wall Street bank valuations, a Credit Suisse acquisition would be too distracting. “Regulators would not want to see UBS take it on either, as it would create too much risk in one entity,” said the person involved in UBS strategy. “They would be creating something that could never be killed.”

What are stake here are not simply matters of global financial stability, or general principles of competition policy, but the 21st century rearrangement, under the sign of globalization, of elite networks in a small and confined society that traces their roots back to the 19th century. Alfred Escher the liberal politician and business leader who founded the predecessor of Credit Suisse as the first bank in Zurich, 167 years ago, and was a great driver of railway industrialization in Switzerland, will be turning in his grave.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters and receive the full Top Links emails several times per week, click here: