There is a chronic and yawning gap between our collective awareness of major social, environmental, political and economic problems, the capacious way in which we address those problems in policy discourse and the resources that are actually mobilized to meet the challenges we can clearly see ahead of us.

Think of the unmet call to turn billions into trillions in pursuit of sustainable development. Or the failure over more than a decade to raise a $100 billion for poor-country climate spending.

One way of interpreting this gap between recognized problems and effective action, is to say that it is not real. Talk is cheap. Our professions of commitment are false. When say we care about problem x, however precisely we may define it, it is not in fact true. We are hypocritical and it is the job of critical analysis to debunk that.

I find that convincing, but only up to a point. Beyond mere hypocrisy there are actual and persistent difficulties in matching means to ends. There is the problem of historical agency, constituting ourselves as an effective collectivity, a “we” that can think and act together. Furthermore, there are obstacles, cognitive and political difficulties, to grasping both the scale of the challenges facing us and means that might be at our disposal if we were willing to act with determination, imagination and disregard for conventions, if we were willing to adopt the attitude of doing “whatever it takes”. I invoke Mario Draghi, former President of the ECB, and his famous speech in the summer of 2012 deliberately, because central banks in 2008, 2015 and 2020 have shown the kind of action that is possible in the face of modern emergencies. There other areas of modern government in recent decades, where we have seen such open disregard for conventional limits.

My hunch, in short, is that we have not only a cynicism problem (bad faith) and a problem of means and ends (a policy problem), but something deeper: A reality problem. Another way of putting this point is that actually situating ourselves in medias res is harder than it might seem. We inhabit historical reality in a weird way. We are, willy-nilly present in the world, we are thrown into it, but we flee cognitively and politically from the stark reality surrounding us.

A case in point is the self-congratulation that surrounds European and American aid for Ukraine which is the subject of my column in the FT this weekend.

The mood at the Munich Security Conference on the topic of aid for Ukraine was, by all accounts, self-congratulatory. And yet Ukraine is at risk of running out of ammunition and its economy teeters on the brink of economic disaster. As the FT piece spells out, this discrepancy is likely explained by all three problems - hypocrisy, policy problems and a problem of perception, a “reality gap”.

This is brought home when you read the report by the team at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy headed by Christoph Trebesch and including Arianna Antezza, Katelyn Bushnell, André Frank, Pascal Frank, Lukas Franz, Ivan Kharitonov, Bharath Kumar, Ekaterina Rebinskaya and Stefan Schramm, on the scale of Western aid for Ukraine.

The Kiel Institute has been tracking Western aid since the start of the war but in their latest report they add a historical section which provides comparative context. Even if you are aware of the basic numbers about previous military-economic efforts, the Kiel report is head-turning.

***

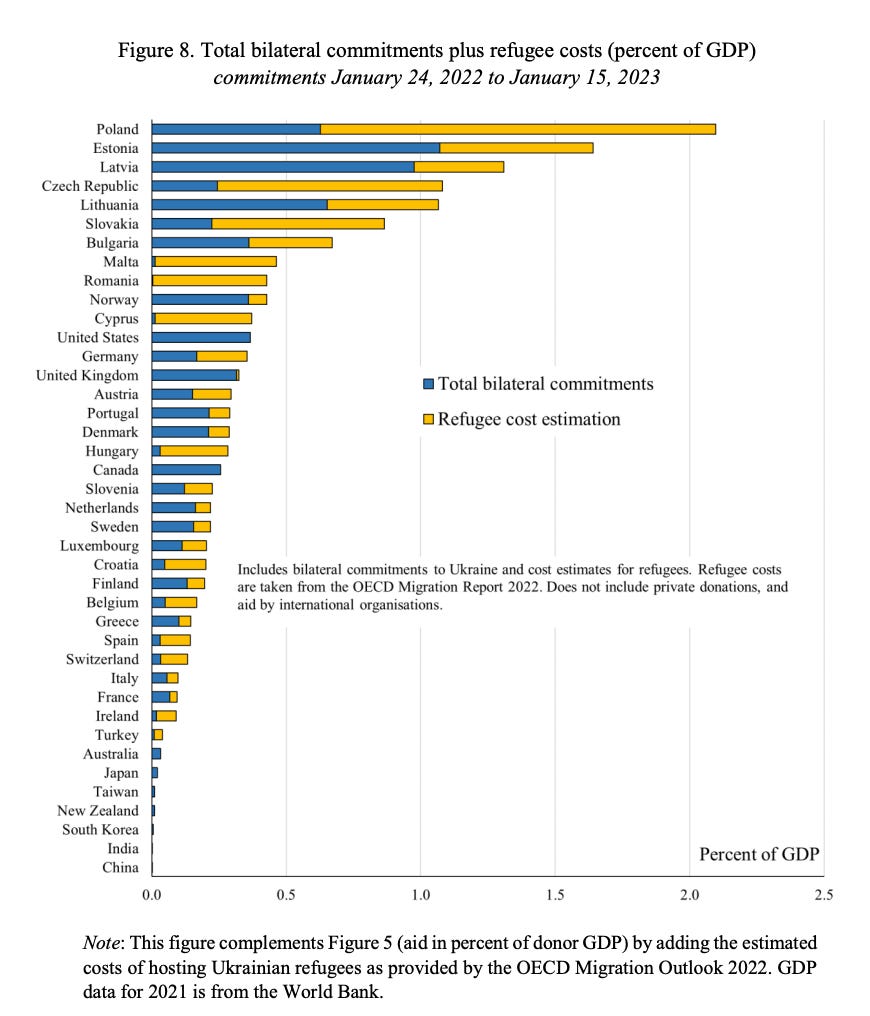

All told, the Kiel Institute dataset tracks €143.6 billion of financial, humanitarian, and military aid committed to Ukraine between January 24, 2022 and January 15, 2023. Keeping track of such a big pile of money is a fiddly business. There are many different channels: collective and bilateral, civilian and military, direct aid and aid in the form of support for refugees. If you add them all up and benchmark against GDP, you end up with this striking compilation.

If you allow for the costs of supporting refugees, as well as military and other bilateral aid, Germany and the United States at 0.375 percent are both contributing similar shares of GDP. The leader, by far, is Poland, which at 2.1 percent of GDP is spending more than 5 times as much in proportional terms as either the US or Germany.

Of course, both the United States and Germany have many calls on their resources. So, the best way to gauge the priority being accorded to Ukraine, is by comparison with other emergencies.

For all the talk from administration officials of America being on a “war-footing”, spending on Ukraine, in fact, falls well short of all America’s military commitments since 1945.

Likewise, Germany contributed far more to the liberation of Kuwait’s oil wells from Saddam Hussein’s in 1991 than it is contributing to Ukraine’s defense against Putin’s aggression.

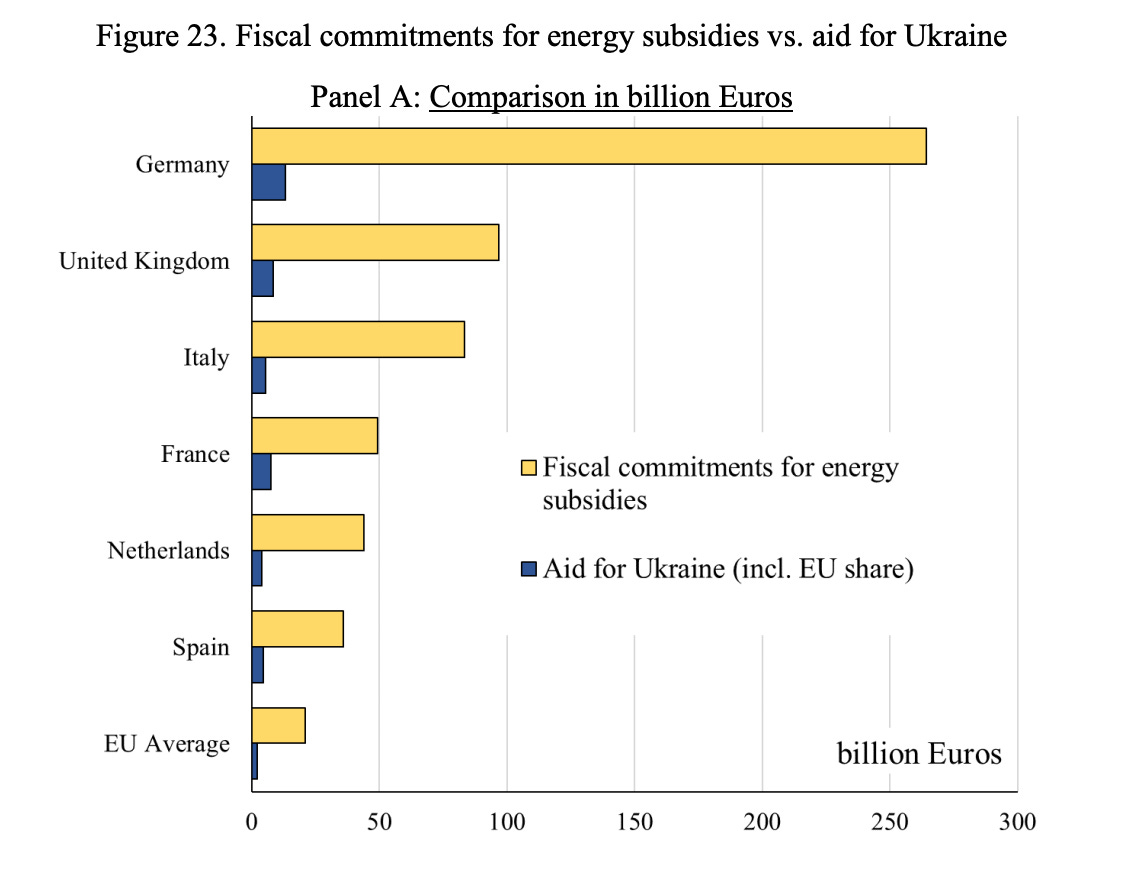

The comparison with civilian emergencies is even more stark. In 2022 all the countries of Europe, at least in Western Europe, committed vastly greater sums to cushioning their population against the energy shock unleashed by Putin’s war, than they did to supporting Ukraine in defeating the aggressor.

With regard to military spending it is not easy to set an upper limit to what is needed on the battlefield. Ukraine’s economic situation is desperate too. But it is somewhat easier to assess in quantitative terms. The figure proposed by Kyiv for its financial needs is in the order of $3.5 billion per month. The United States and Europe have committed to providing enough to cover that. But as the monthly data show, those payments do not arrive in a steady or reliable fashion.

***

The point of my op-ed is not that Europe and the United States should deliver vastly greater aid to Ukraine. One may want to make the case for that, but that is a separate issue. The point of my op-ed is that the Kiel data reveal a vast gap between the declared intentions of the United States and Europe in backing Ukraine and what they are actually delivering.

So what explains this shortfall? This raises the questions with which we began this newsletter. Are the Western powers cynical in promising to stand by Ukraine? Are they implicitly steering towards a stalemate? Do they actually favor a Ukrainian victory, but incompetence and “friction” causes them to fall short in matching the necessary means to the desired ends? Or are they struggling with a “reality gap” - failing to grasp the scale of what might be needed and what on other occasions and for other purposes they have been able to deliver? Personally, I think it is a mixture of all three.

One thing is for certain: The modesty of the support provided by its Western allies, leaves Ukraine’s war effort precariously balanced and the course of the war in 2023 highly uncertain. Ukraine may pull through. Its military are fighting remarkably well. Perhaps Russia will crumble. But if it does not, we should likely expect the “reality gap” to close in the direction of greater financial and military aid. There is evidence for this in the Kiel data.

December 2022 - the 11th month of the war - saw the largest commitments of military aid to date. As Ukraine’s own reserves are progressively worn down, we should surely expect that trend to continue.

Of course, there are also risks to escalating support for Ukraine. Most notably the West still needs to be concerned about the Russian reaction. Managing the crisis requires balancing. What is striking about the current moment is how opaque the terms are under which that balancing is being performed. It leaves the impression of decision-making stumbling from one crisis and one problem to the next. It is certainly a pattern that we should fear to see generalized: The reality gap closing under the pressure of crisis, rather than as a result of strategic foresight and leadership.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

Once you understand that the principal beneficiaries are western contractors, everything makes sense.

I'm not interested in the gap... I'm interested in my country ceasing to overthrow governments and caused civil wars that require their neighbors to react by installing governments that are openly hostile to them on their borders and that abuse, murder and discriminate against 50% of their own population. America is on the wrong side of the civil war in Ukraine. Point blank. Nothing else to be said.

And what's more tragic is America caused the escalation of these tensions to war by funding and arming the right wing extremist and Nazis within that country since World War II because they wanted to destroy the Soviet Union. Which, by the way, meant they were funding them INSIDE of the Soviet Union until 1991. Only the most disgusting human beings in the world would fund the war criminals who committed mass genocide against the Soviets because they think their ability to profit might be affected. Our CIA has a lot to answer for. They should be disbanded and tried in international courts for their crimes against humanity.