As 2023 begins, policy-makers around the world are still trying to figure out how to respond to the lurching acceleration of inflation that began in the second half of 2021 and that now seems to have crested.

In 2022 it was all hands on deck. In Europe, where the energy price shock was most intense, a wide range of policies were debated and deployed including price controls and large fiscal subsidies. Now, as the sectoral price shock begins to ebb, the focus is less on price controls or large fiscal transfers and once again on the central banks. The balance the central bankers have to strike is delicate and their main instruments - interest rates and quantitative tightening - are blunt. How quickly will they move from QE and QT? Will they continue to raise rates in large or small increments? Where will they stop? What is the terminal rate? And when they might contemplate bringing rates back down again?

The Fed has signaled that though inflation may be slowing it remains far above the 2 percent target and it will remain in contractionary mode. It will continue to raise rates, but at a slower pace than in recent months. The surge in global interest rates driven by the Fed in 2022 was dramatic. It was the most sweeping tightening ever seen. This put pressure on every central bank, even the Bank of Japan, where inflation is only just rising to the target band. The BoJ now faces huge pressure in the bond market to modify its policy of zero interest rates (yield curve control).

The European Central Bank is in a particularly difficult position, not just because the inflationary wave has taken time to unfold in Europe, or because of the idiosyncratic nature of the war shock, and ongoing concerns about energy markets. What is at stake in the ECB’s decision is the problem of how to balance inflation-control with the underlying fragility of the European economy, the divergence between its parts and, for much of Europe, the miserable track record of stunted growth that stretches back to the Eurozone crisis of 2010-12 and the financial crisis of 2008. The ECB’s excessively conservative monetary policy stance, the failure to thoroughly restructure Europe’s banks and the fact that it took until 2012 to stabilize sovereign bond markets and until 2015 to launch active QE, is widely seen as co-responsible for this malaise. The risk is, that adopting a hawkish anti-inflation stance, as many voices on the ECB Council have recently been advocating, the ECB will further jeopardize Europe’s growth prospects. Given the inflation rate in many parts of Europe and the limited tools at the ECB’s disposal, there may be no alternative. But we should be aware of how high the stakes are.

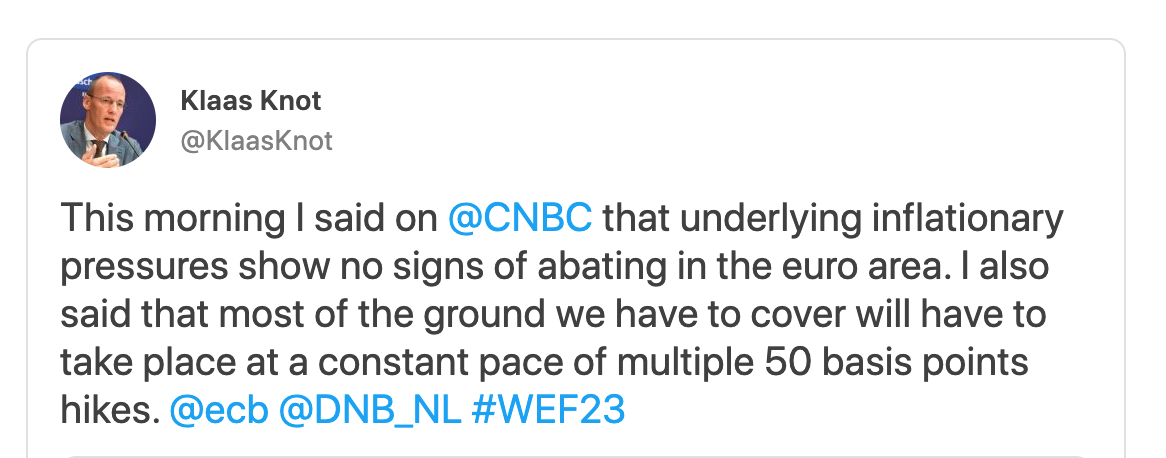

When a key figure like Klaas Knot of the Dutch central bank demands a determined course of large, 50 basis point hikes, the question that lurks in the background is: how much tough monetary policy can Europe actually stand?

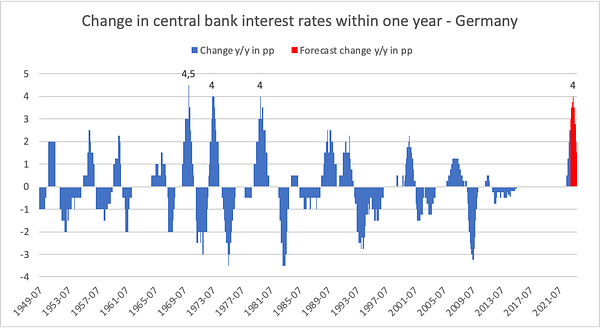

Of course, inflation also generates social and political risks and those are to the fore in Europe right now. But the interest rate hike being advocated by the ECB hawks is extremely severe. The Fed may have normalized the 50 basis point hike, but for much of Europe it would the be most severe monetary tightening ever attempted.

The Italian debt problem lurks in the background. Rising rates put pressure on the weakest borrowers and at some point that can become a doom-loop. But let us assume that the risk of exploding spreads can be managed between Rome, Brussels and Frankfurt. Let us grant that the unity of the Euro is not in question and focus, instead, on macroeconomics. How much growth retardation, how much more divergence between weaker and stronger regions can Europe take? How toxic and dysfunctional will the social and political consequences of conservative monetary management and very low growth turn out to be?

A tightening on the scale being advocated by Euro-hawks implies taking risks with growth, employment and investment. It will constrain choices in both the public and private sectors. It puts in play every borrowing and spending decision, including priorities like the energy transition, security policy etc. Of course, those are the dilemmas that central bankers professionally weigh up. But in weighing those options in Europe in 2023 it is important to be clear about the historical backdrop.

If you want to slow inflation by applying the cosh of interest rate increases to aggregate demand, you have to start by asking whether aggregate demand is the main cause of European inflation. Otherwise, the amount of pain you may have to inflict will be disproportionate. The overwhelming majority of evidence suggests that aggregate demand is far from being the main driver of European inflation. n these figures from the German expert commission which show the surge in inflation in energy prices and consumer prices, the component that is domestic aggregate demand is colored yellow.

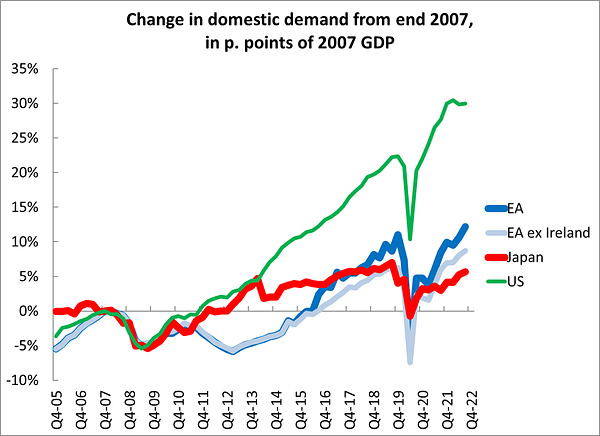

But beyond the immediate causes of inflation, in weighing the macroeconomic policy options for 2023 we also need to consider the track record of demand management in Europe over the last 15 years. The benchmark here is not a 2 percent inflation target, but the development of the other major economic hub in the West, i.e. the United States. The conclusion is stark.

Data from Brad Setser starkly illustrates just how far the trajectory of growth in European domestic demand - consumption, investment, government spending (everything except exports) - has lagged behind that of the United States.

It is important to focus on domestic demand - consumption, investment, government spending - because, following the German example, Europe has relied heavily on exports (foreign demand) to drive growth. This means that Europe’s GDP numbers make Europe’s policy stance look more expansive than it actually has been. Excluding Ireland’s GDP numbers is important because they are spectacularly distorted by its role as an offshore tax haven.

The message of the graph is that over the period since 2007 the trajectory of Europe’s domestic demand has been profoundly depressed. The index here is not annual growth, but total domestic demand relative to the 2007 level. America’s green line shows what a growing economy looks like, adding increments every year. By contrast Europe’s domestic demand took eight years to recover back to its 2007 level. For most of the period between 2007 and 2022 Europe’s domestic demand level has been considerably more depressed than that of Japan.

The COVID shock took Europe to a new low - lower even than in 2012 at the trough of the eurozone crisis. The rebound since 2020 has been relatively vigorous. But, in 2022, Europe’s growth trajectory remained below the modest recovery trend from 2012 to 2020. Indeed, the contrast with the US is even more sharp if we turn up the resolution and look at the rebound from COVID in 2020 and 2021.

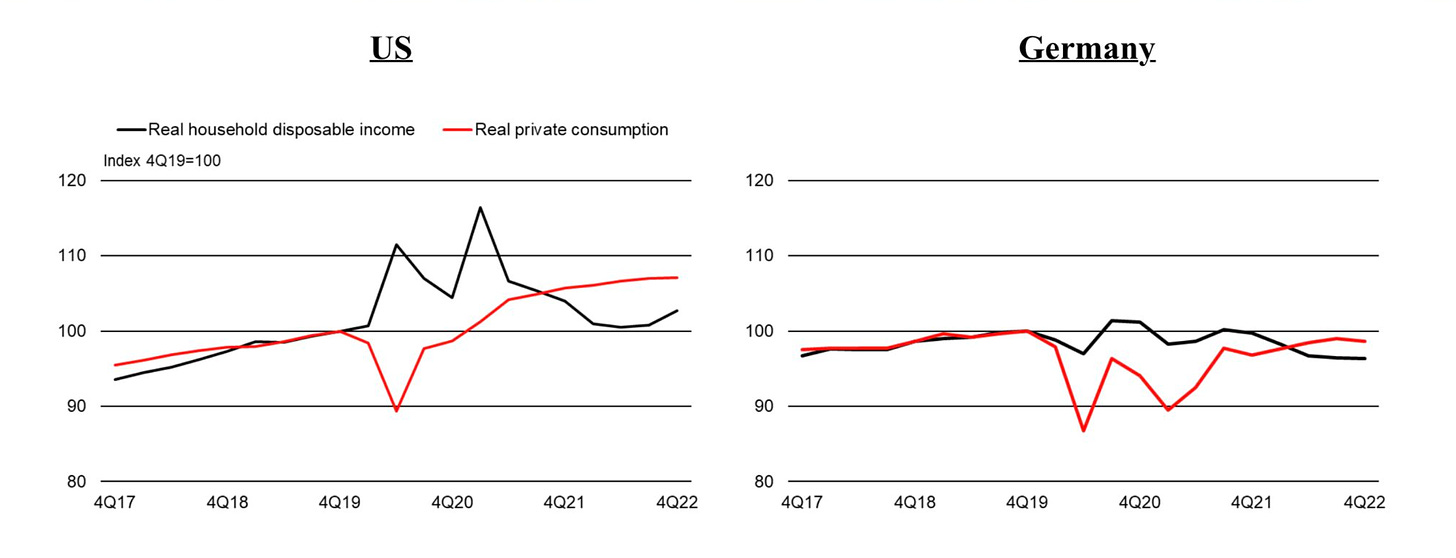

The divergence in European and American policy responses to the Covid-shock is brought out by this stark graph from Erik Fossing Nielsen, chief economists at Unicredit. America’s COVID-stimulus was so gigantic that disposable income actually surged during the pandemic. By 2021 US consumption spending had recovered to its pre-pandemic trend. In Germany, by contrast, the stimulus was more modest and consumption has plateaued and now dipped below its 2019 levels.

So, Europe inflation hawks are advocating for a historic interest rate hike to counteract a temporary inflationary surge, which is not principally driven by aggregate demand, in an economy which for 15 years has been suffering from a chronic lack of domestic demand and which is falling far behind the United States. It is a blunt force, high risk policy which may have historic ramifications for Europe.

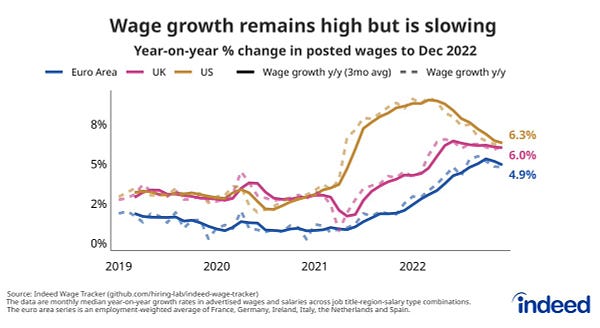

Inflation hawks argue that it is crucial to ensure that inflationary expectations do not become entrenched, in the form of persistent wage increases. But, of this there is remarkably little evidence. The “second round effect” of wage increases has been far less pronounced in Europe than in the US or the UK and the rate of wage increases began to slow at the end of 2022.

One of the more likely candidates for a wage-price spiral is France. On France’s idiosyncrasies this expert take from the chief economist of the French Treasury is fascinating.

So if the empirical evidence for a serious inflation problem that would warrant a draconian response is relatively weak, what then motivates the inflation hawks?

Ideology and politics are no doubt one component of the answer. Inflation hawks are uncomfortable with inflation. They regret the fact that the ECB acted too slowly. They want to see more determined action to prove a point. Another answer to the question of who is an inflation hawk in the precincts of the ECB and why, may be which national economies they represent.

Source: ITCMarkets

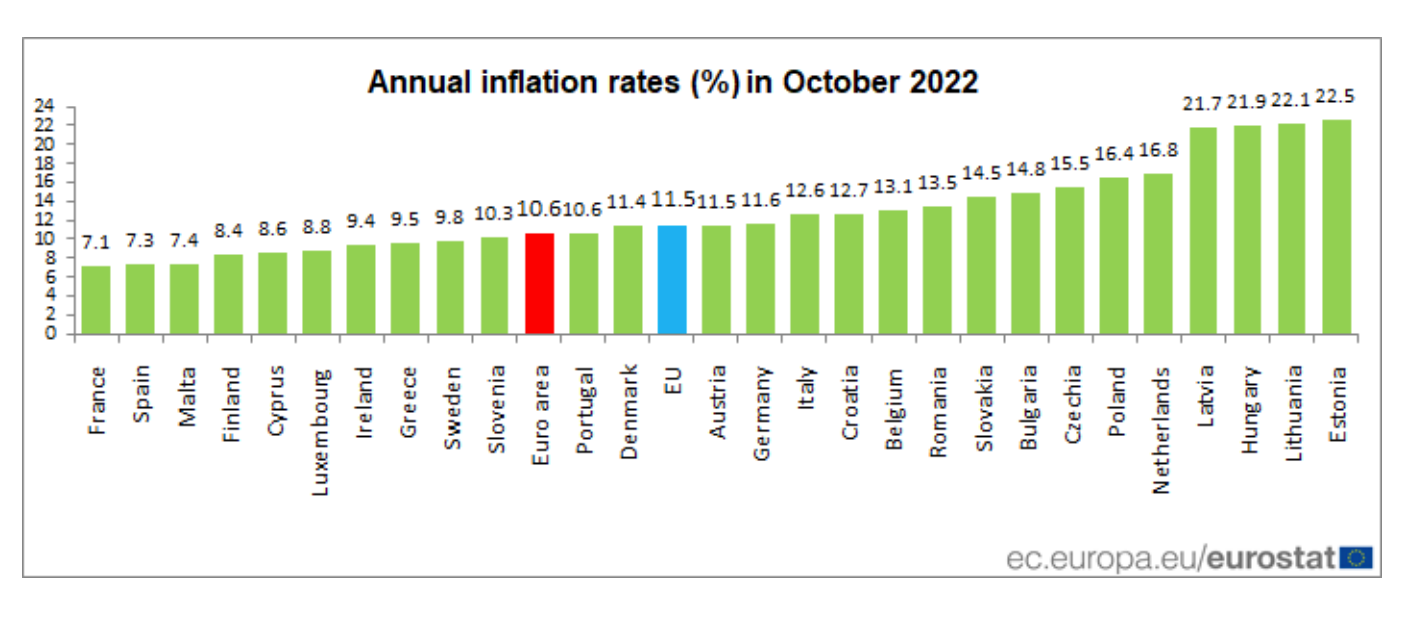

Nationality matters, because the divergences within the Eurozone in terms of macroeconomic balance are so dramatic. Right now, inflation rates in Eastern Europe are dramatically higher than in the West. They are also far higher in the Netherlands (16.8%) than in France and Spain (7%). In light of those numbers it is hardly surprising that the representative of the Dutch central banks feels a responsibility to give absolute priority to fighting current inflation by means of sustained interest rate increases. When inflation exceeds 16 percent your interest in complex rationalizations shrinks.

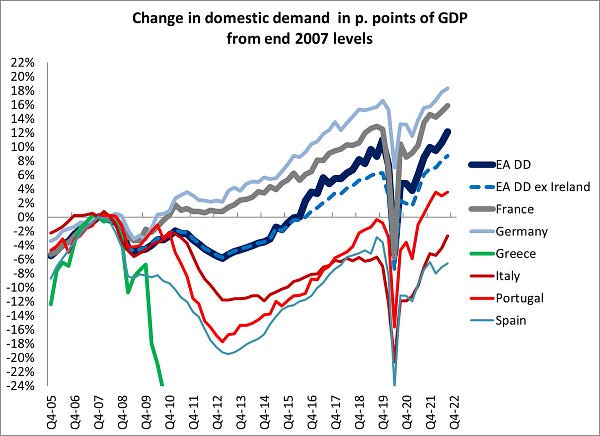

But history also matters. The failure of aggregate demand management in the Eurozone becomes truly apparent only when we break it down by country.

Whilst Germany falls well short of America’s domestic demand growth, it has at least experienced real growth. By contrast, in Q4 2022 domestic aggregate demand in Italy and Spain was still at levels lower than in 2007. Portugal is barely above. Greece has dropped off the chart altogether. So, whereas for Germany or the Netherlands or the Baltics a temporary interruption to growth, or even a mild recession may be a reasonable scenario, for Italy or Spain it would be a far more alarming prospect.

How then should the ECB proceed?

As Erik F. Nielsen argues in a recent note the ECB needs, urgently, to clean up its communications and step back from a policy-making process guided by “present inflation, political pressure via the tabloids and “gut feelings””. It needs to reassert the role of forward-looking models and clarify its expectations with regard to broader “financing conditions”. It also needs to be clear that if Europe enters a real recession then the terminal rate of 3.5 percent may be too high.

Meanwhile, in light of the difficulty of interpreting the current macroeconomic situation, differences in ideology, political positioning and the real differences between the member states of the EU both currently and over the last 15 years, it is hardly surprising that there are differences of opinion and vigorous debates on the ECB. It would be frankly alarming if this were not the case. Whereas the Fed has embraced this diversity of views, the ECB has tried to obscure these differences. It carefully edits its minutes and dispatches centerists spokespeople like the excellent Philip Lane to spread sweetness and light. Disputes within the bank filter through to the public by way of more or less openly sources journalism and coverage in news outlets like Bloomberg or the FT. Given the tensions within the Eurozone construction it is easy to see why a premium has been put on closing ranks and presenting a unified view. But under the present circumstances that seems increasingly unrealistic. As Shahin Vallée and Sander Tordoir have recently argued in an op-ed for the DGAP the time may have come for the ECB to embrace its differences and to find procedures for allowing the big differences on the Council to be ventilated in public. Under present circumstances however one should expect any new era of openness to begin with a bang not a whisper.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

The emphasis by KNOTT et al on raising rates is because Lagarde is so fearful of fragmentation of sovereign debt spreads if QT begins in earnest.The German debt is the HQLA putting a bid to Bunds as it is used for collateral purposes.Until the EU has genuine fiscal harmonization the fear rests on Lagarde to take the least disruptive route----raing rates but even Knott noted in the FT three weeks ago that over a 1/3 of the voters desired 75 basis point increase

The hawk/dove analysis chart seems to be a Protestant/Catholic chart, except for Austria.