In the last ten years, the familiar boundaries of the political debate on the US have been challenged by a convergence of arguments about racial justice, economics and inequality.

This conjunction in its contemporary form dates back to the early 2010s when the ferment in economic debates in the aftermath of 2008 and the differential impact of that crisis on black and latino households, coincided with the election of Barack Obama, the Occupy movement, which spawned the 1 percent v. 99 percent discourse, the upsurge in interest in inequality supercharged by the success of Thomas Piketty’s book and the eruption of Black Lives Matter in July 2013.

A second phase of coalescence arrived with the mobilization against the Trump Presidency, the Green New Deal of 2018, the sudden salience of MMT, the differential impact of COVID and then, in 2020, the killing of George Floyd and the protests that followed.

It is a striking, for instance, how central concerns of racial justice are to the environmental justice and Green New Deal movement in the US. Environmental justice emerged in the US in the 1980 as a movement of communities of color that was separate from and at times opposed to predominantly white environmentalism and the organized lobby of “Big Green”.

Opposition to carbon pricing on the part of the environmental justice movement in the United States reflected the experience with such systems in California where they were seen as enhancing inequalities between majority and minority communities. This gives climate politics in the US a very different coloration to Europe.

One of the effects of this intersection of movements was also a reappraisal of history and specifically the social and economic justice components of the civil rights movement and the thinking and politics of Martin Luther King.

I tried to do justice to this in the Ones and Tooze episode that aired in time for MLK day on 16 January.

My guide on these issues has long been David Stein’s fascinating work on the economic policy thinking of the civil rights movement, the Freedom Budget, the full employment guarantee and Coretta Scott King.

The Freedom Budget was a radical Keynesian proposal to pursue a conjoined program of racial and social justice combined with full employment. In its thinking it was a remarkably cogent statement of left Keynesianism.

I attach the reader that I assembled from materials freely available on the web here:

Teaching the topic I added readings from William Darity Jr, Darrick Hamilton and Mark Paul.

For the deeper background of the development of Black American economics and its approach to the intertwined questions of social and economic disadvantage and racism, check also this fascinating lecture by Nina Banks on the remarkable Sadie T.M. Alexander. In 1921 Alexander was the first Black American to receive a PhD in economics in America.

For this year’s Podcast on MLK day, I added to my reading Michael K. Honey’s To The Promised Land. Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice.

Honey does a wonderful job of unpicking the threads that make up King’s thought on social and economic matters and intertwining the evolution of King’s thinking about economic and social justice with his activism in support of organized labour.

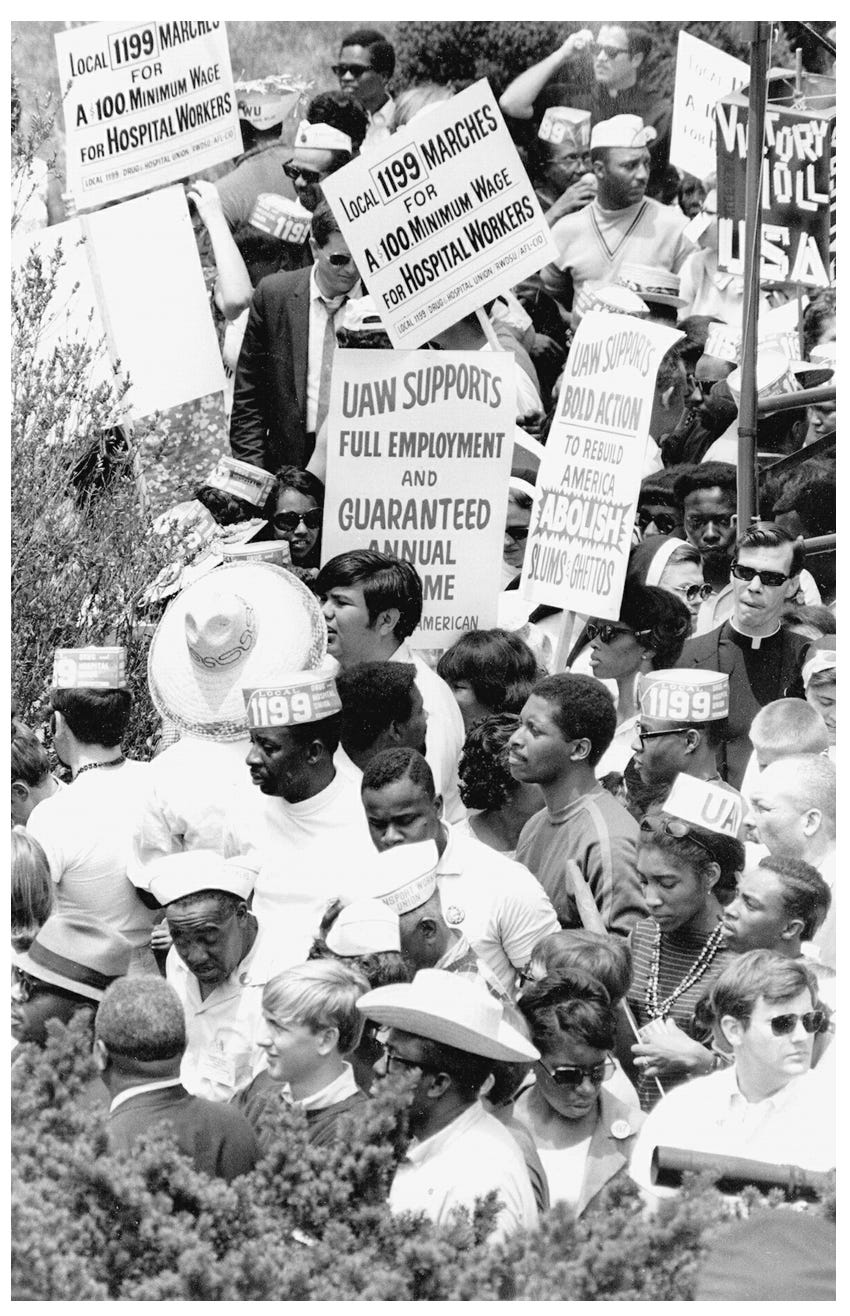

As he shows, in the months that followed King’s assassination the United States saw not just rioting but a remarkable convergence of anti-war, social justice organizing in the Poor People’s Movement. Note the UAW banners demanding full employment and a guaranteed annual income.

Demonstrators from across the country converge on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., during the Poor People’s Campaign on June 19, 1968.

By twisted and circuitous routes ably traced by Stein and Patrick Andelic what emerged from this radical mobilization was, eventually, the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act, which was signed into Law by Jimmy Carter in 1978. This, in turn, is conventionally seen as providing one of the pillars of the Fed’s “dual mandate” for both price stability and maximum employment. As Lev Menand has recently argued that too may be an ex post construction. In the 1970s Congress actually prioritized credit expansion with a view to ensuring full capacity utilization from which maximum employment and stable prices (proof against deflation) would emerge as consequences. It was the currents dominant in global economics in the 1980s, not the mandate of Congress that made the Fed into the overarching macroeconomic regulator.

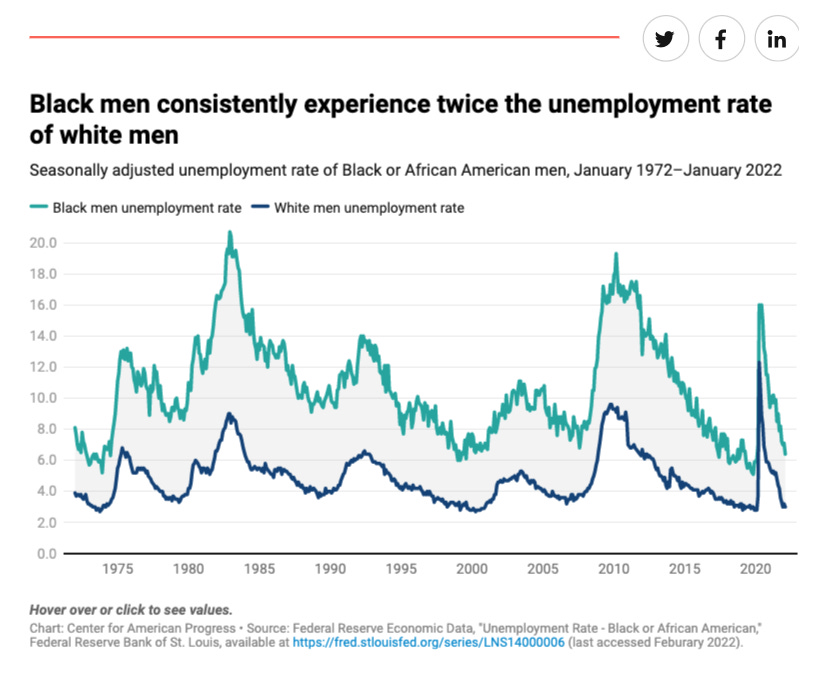

It was a twisted completion of that arc which meant that in 2021, in the aftermath of the COVID crisis and the upsurge of BLM, the Federal Reserve began to recognize the macroeconomic balance between inflation and unemployment as one that engaged issues of racial justice.

Source: Lorena Roque Rose Khatta, Arohi Pathak 2022

It seems that the arc of history bends towards the technocratic incorporation of once radical currents of political economy. It thus behooves us on an occasion like MLK day to push against this tendency.

As Honey drives home, it is convenient for mainstream American life to remember and honor “King and his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)” for their brave struggle to “redeem the soul of America” by seeking equality before the law, integration, and voting rights for all. But we do not do King or his movement justice if we leave it at that limited agenda. They were radical and explicit in demanding that those liberal freedoms would mean little if they were not accompanied by a profound change in American society and the structure of its economy. That went well beyond the Fed incorporating black male unemployment into its macroeconomic dashboard.

****

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

One of the other things that they won't tell you is that, at the time of his death, MLK was in bad odor among liberals because of his opposition to American imperialism in general and the Vietnam War in particular.

Is there analysis on the specific drivers of unemployment rate differentials by race? For example how does adjusting for educational attainment change the above graph? Would be helpful to understand more discretely the impacts of systemic racism factors, idiosyncratic racism, and other explanatory factors that could more clearly inform policy.