Chartbook #171 Finance and the polycrisis (2) The global housing downturn.

In this precarious moment - in the fourth quarter of 2022, two years into the recovery from COVID - of all the forces driving towards an abrupt and disruptive global slowdown, by far the largest is the threat of a global housing shock.

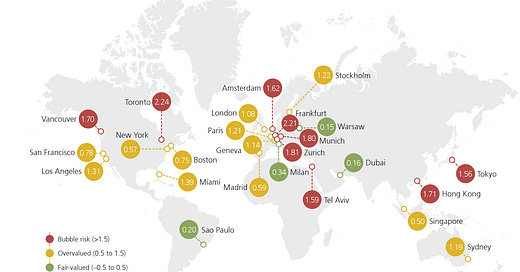

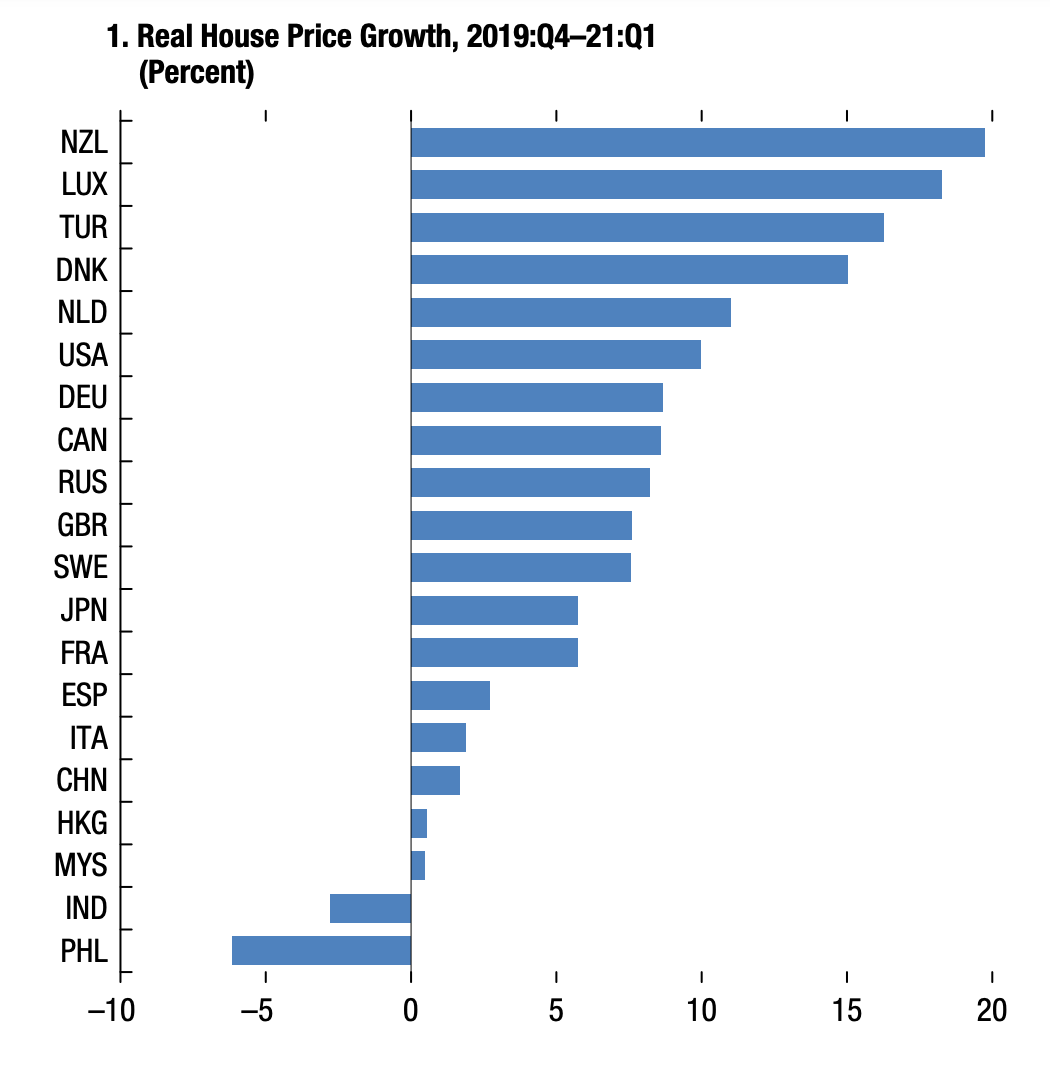

There was some anxiety even before 2020 about escalating house prices in hot spots around the world, but the pandemic delivered an unprecedented jolt to housing markets. In 2020 and 2021 house prices surged, causing the IMF to sound the alarm in its October 2021 Financial Stability Report.

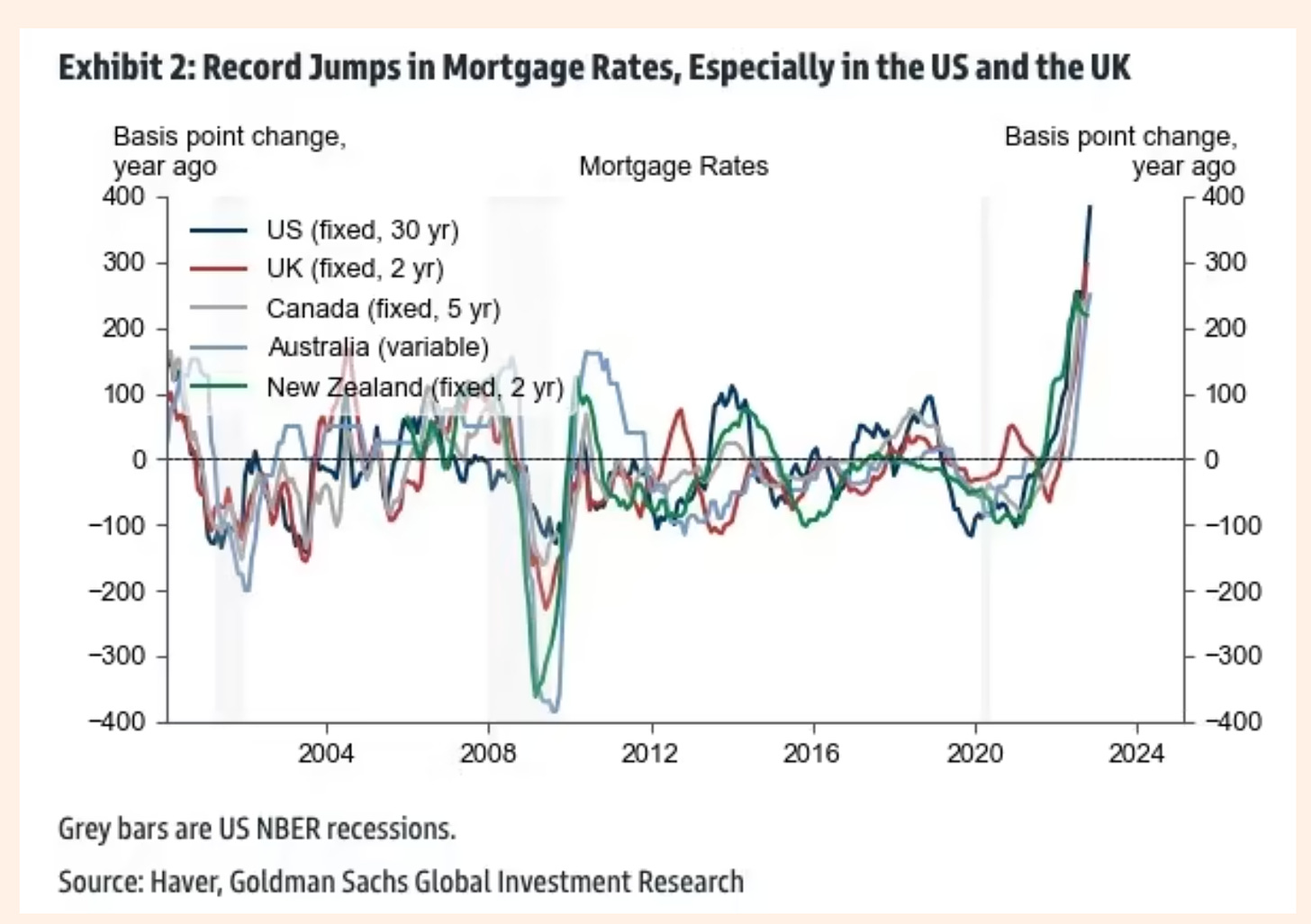

In the second half of 2021 inflation accelerated due to supply shocks and in 2022 that surge broadened. With interest rates being pushed up with unprecedented speed, the question now is whether after the unprecedented shutdowns of 2020 and the rapid rebound of 2021, the winter of 2022-3 will see the beginning of a global housing crash. If this were to occur, the impact would be huge.

In the global economy there are three really large asset classes: the equities issued by corporations ($109 trillion); the debt securities issued by corporations and governments ($123 trillion); and real estate, which is dominated by residential real estate, valued worldwide at $258 trillion. Commercial real estate ($32.6 trillion) and agricultural land add another $68 trillion. If economic news were reported more sensibly, indices of global real estate would figure every day alongside the S&P500 and the Nasdaq. The surge in global house prices in 2019-2021 added tens of trillions to measured global wealth. If that unwinds it will deliver a huge recessionary shock.

In regional terms, as a first approximation, think of global real estate assets as split four ways, with the US, China and the EU each accounting for c. 20-22 percent and 35 percent or so belonging to the rest of the world.

The housing complex is at the heart of the capitalist economy. Construction is a major industry worldwide. It is one of the classic drivers of the business-cycle. But beyond the constructive industry itself, the influence of housing as an asset class is pervasive. Compared to equities or debt securities, residential real estate is owned in a relatively decentralized way. Homeownership defines the middle class. And for the majority of households in that class, those with any measurable net worth, the home is the main marketable asset.

Middle-class households are for the most part undiversified and unhedged speculators in one asset, their home. Furthermore, since homes are the only asset that most households can use as collateral, they pile on leverage. For households, as for firms, leverage promises outsized gains, but also brings with it serious risks in the event of a downturn. Mortgage and rental payments are generally the largest single item in household budgets. And household spending, which accounts for 60 percent of GDP in a typical OECD member, is also responsive to perceived household wealth and thus to home equity - the balance between home prices and the mortgages secured on it. For all of these reasons, a surge in mortgage rates and/or a slump in house prices is a very big deal for the world economy and for society more generally.

To cushion these risks, many rich societies have a middle-class welfare state that subsidies and supports homeownership, through tax breaks, subsidized housing credit, protections for mortgage debtors and incentives for the private construction of rental accommodation. Homeownership and rental accommodation are at the heart of political economy. These systems are regularly tested by the cyclicality of the real estate market itself, where boom and bust cycles have alternated back to the 19th century and by macroeconomic shocks like the one we are currently experiencing. The kind of policy-driven interest rate hike we are seeing in 2022 sends a shockwave through the system.

Source: Goldman Sachs via FT Alphaville

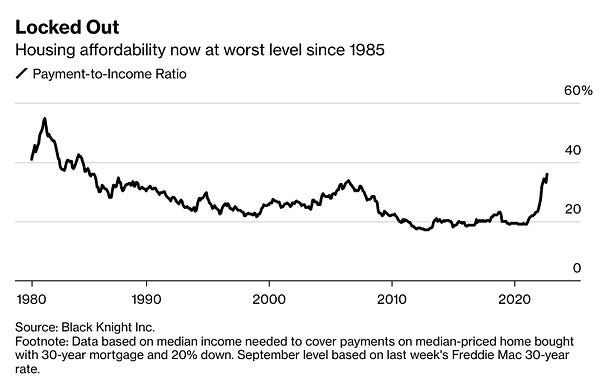

The current surge in mortgage costs across much of the english-speaking world, is the most dramatic seen in decades. In the US in the course of barely more than half a year mortgage rates have more than doubled, crossing 7 percent for a 30-year fixed in September.

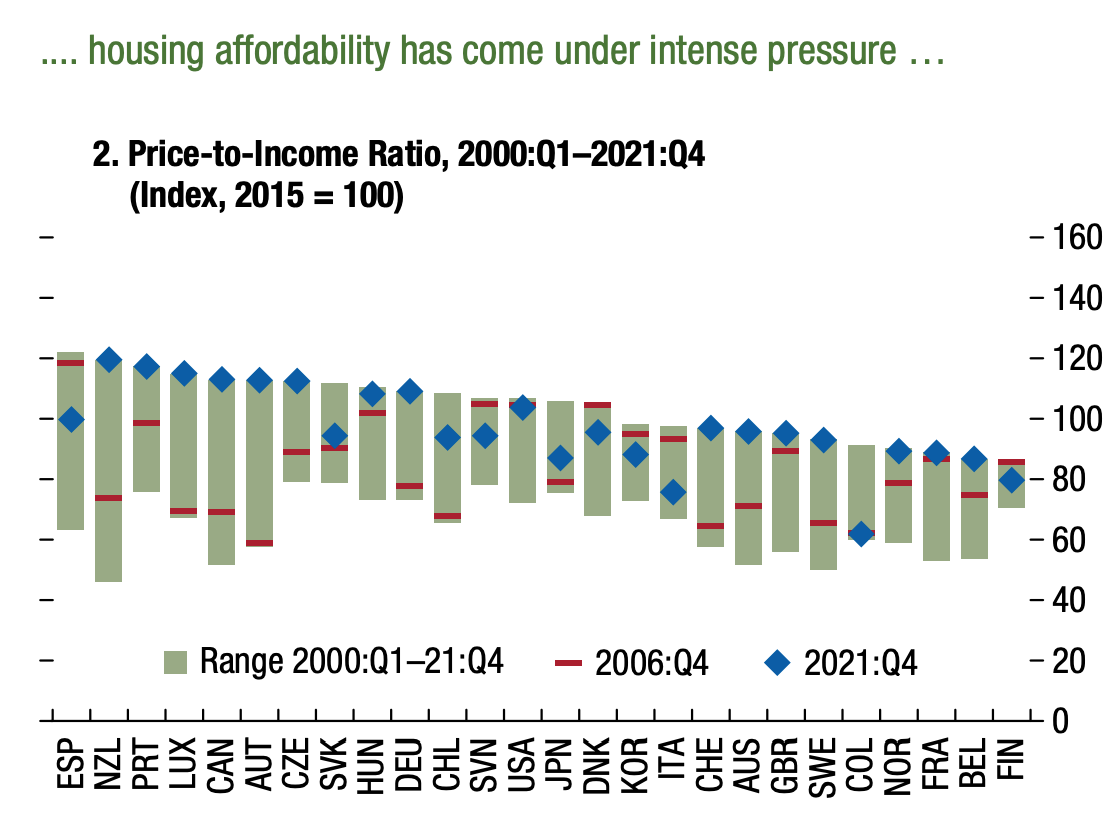

The impact of rising prices and rising interest rates is to crush affordability. An index of US housing costs in relation to income is at highs not seen since the era of Paul Volcker.

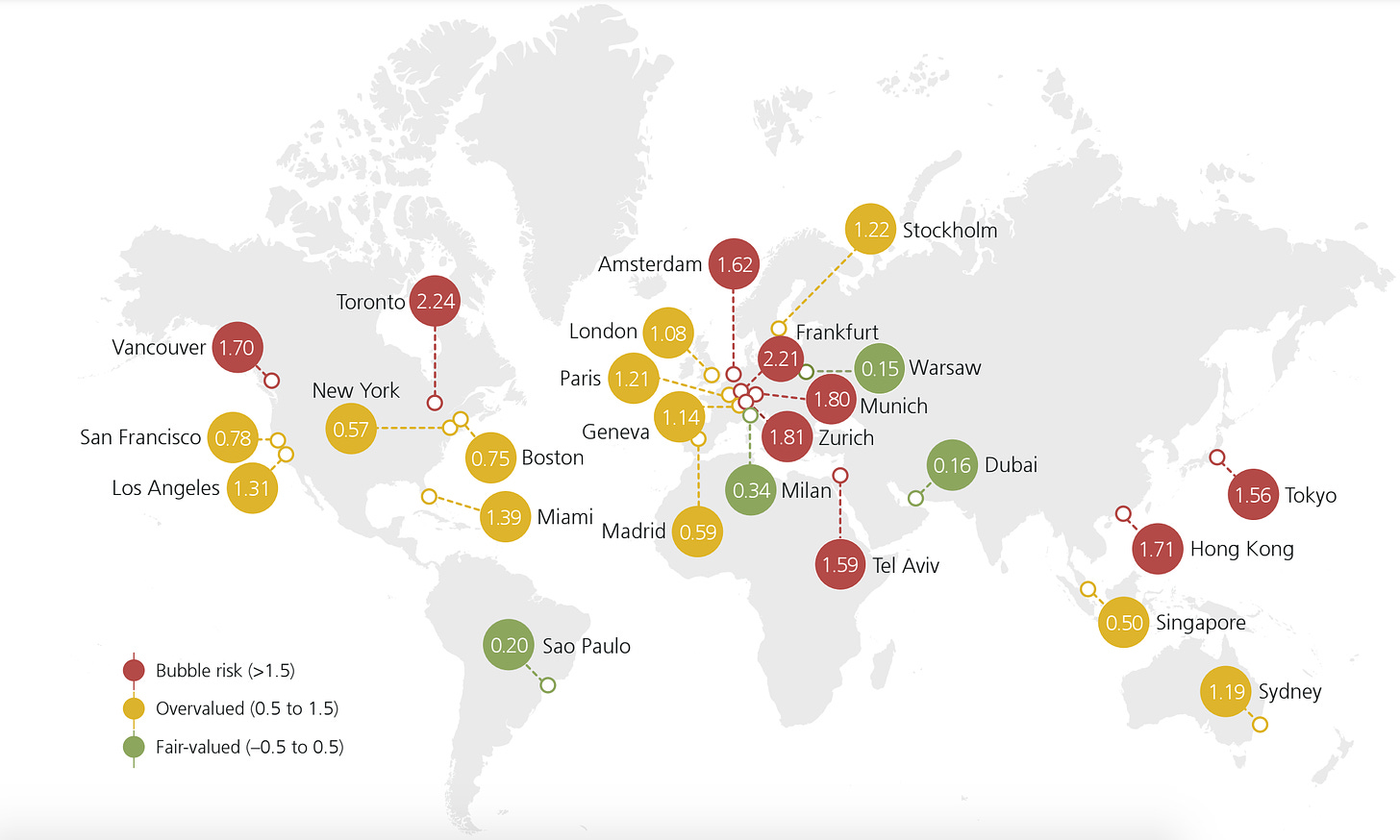

Around the world in 2022 house prices relative to incomes hit historic highs.

Source: IMF GFSR Oct 2022

Unsurprisingly, given these pressures, demand for mortgages is collapsing. As the Economist magazine describes it, the math is simple:

Someone who a year ago could afford to put $1,800 a month towards a 30-year mortgage. Back then they could have borrowed $420,000. Today the payment is enough for a loan of $280,000: 33% less. From Stockholm to Sydney the buying power of borrowers is collapsing. That makes it harder for new buyers to afford homes, depressing demand, and can squeeze the finances of existing owners who, if they are unlucky, may be forced to sell.

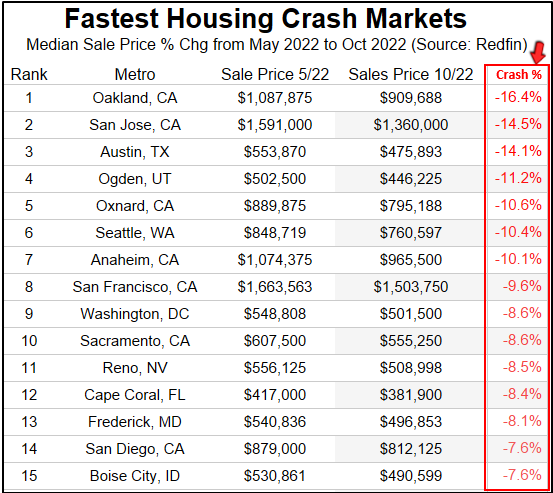

By October 2022 reports were coming in from across the United States of rapidly falling housing prices.

The very fact that house prices are falling reverses the psychology of the market. As one housing market expert told the FT:

“The fact of prices declining rather than rising is a watershed moment … We really haven’t seen anything like this since 2010 or 2011. [ . . . ] This summer marked the end of that long bull run for home value appreciation in the US.”

But the US is far from being the most overpriced in the world. Nor is London the greatest hotspot. Canada is probably the most overheated market and it is seeing a savage downturn. According to the FT, Toronto has seen a 96 per cent nosedive in single family home sales and an 89 per cent fall for condos. Across the country as a whole condo prices are down by 9% since the start of the year. In Europe, Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Munich and Zurich, all look set for a selloff, as do Hong Kong and Tokyo in Asia.

Source: UBS

It used to be said that in the United States, housing was the business-cycle. This worked through construction investment. In China this is still to a considerable extent true. But in the West, since the early 2000s, as housing construction has declined as a share of gdp, the link has attenuated. What matters more, as Mian, Rao and Sufi argue, is the impact on household balance sheets and thus on consumption. Most dangerous of all, as Jorda, Schularick and Taylor have argued in various papers, is the potential for a housing setback to trigger a comprehensive financial crisis.

That was the horror scenario that played out in 2008. In 2021 the Chinese regime deliberately pricked its housing bubble and is now struggling to catch the pieces as they fall. How large the impact will be both at home and abroad remains to be seen. That will be the subject of a subsequent post. For the rest of the world a full-scale mortgage-driven banking crisis does not seem like a likely scenario.

First and foremost, mortgage lender seem more robust. Banks in Europe are more tightly regulated. And in the US the entire mortgage finance system has shifted from universal banks like Citi or Bank of America, to non-bank mortgage providers backstopped by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored mortgage banks. Weaker non-bank mortgage lenders in the US are already beginning to fail, but the risks of systemic contagion seem limited, at least so far. Fully two-thirds of US mortgage are today securitized by way of the GSEs, allowing the vast majority of US home buyers to borrow on favorable and fixed terms over a 30 year term.

Furthermore, though the real estate market has boomed in recent years, the deleveraging that occurred after 2008 significantly reduced the overall burden of household debt in the US. Since 2008 mortgage lending in the US has again been concentrated on those with the top creditor scores. In 2019 60% of mortgages went to borrowers with scores above 760. And in the first quarter of 2021 73% of mortgages went to borrowers with very good credit scores. Only 1.4% were granted to subprime borrowers. Even if home prices were to fall significantly, home equity remains strong, so that the percentage of households that would find themselves underwater with negative equity is small. Even a 15 percent price decline is predicted to leave only 3.7 percent of households underwater compared to 28 percent in 2011.

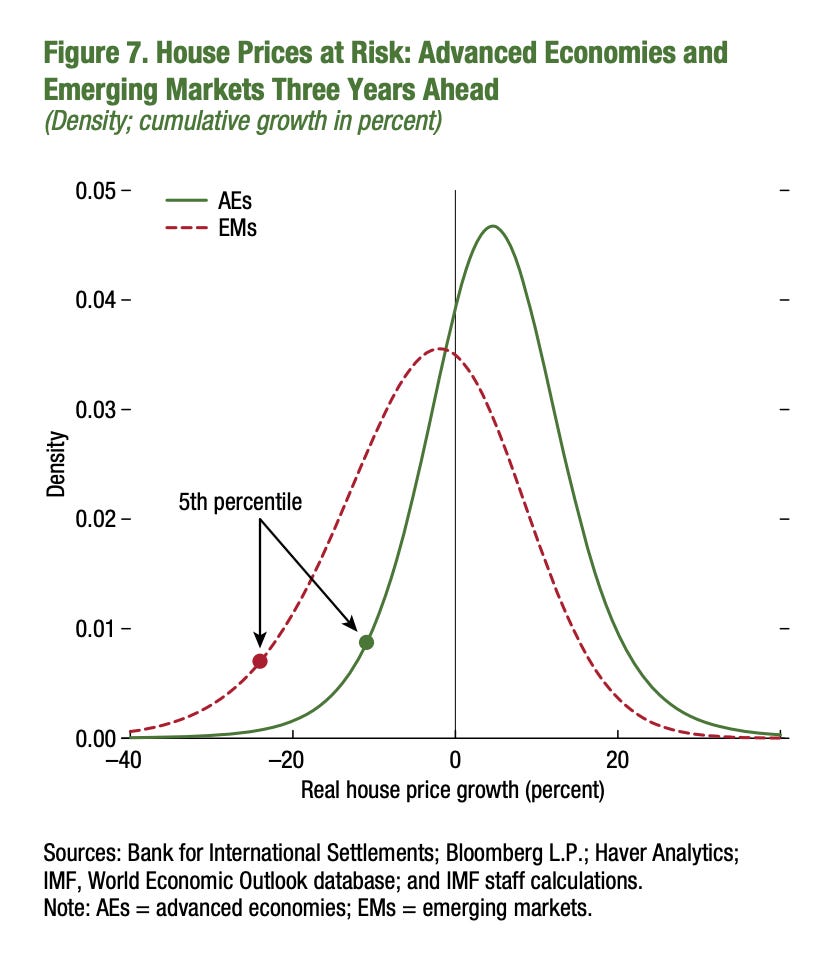

Source: Economist

The risk of an acute housing driven crisis is greater in Canada, which is already experiencing dramatic falls in house prices, and in South Korea and the Nordic countries where household debt ratios are very elevated. Sweden’s central-bank boss has likened his situation to “sitting on top of a volcano”. 80 percent of Swedish loans have rates fixed for two years or less. Half of all New Zealands mortgages are due for refinancing in 2022. Millions of British homeowners could find themselves under severe pressure from rising mortgage bills. The IMF, meanwhile, is most concerned about emerging markets, i.e. first and foremost China. The IMF’s outlook has darkened considerably in the last 12 months and in its worst case scenarios, housing prices in emerging markets crash by as much as 25 percent. That would be a devastating blow to the emerging global middle class.

Source: IMF

The economic shock delivered by a global housing downturn will be severe. Nothing would more rapidly extinguish the flames of inflation. But the shock will not be confined to the economic sphere. If the polycrisis is also a legitimacy crisis, then amongst the various shocks threatening elite claims to authority, the housing situation is far more serious than, for instance, the debacle in crypto, or even the transitory problem of inflation.

As Robin Wigglesworth at FT Alphaville notes

Mortgage holders tend to be wealthier, and tend to vote. Mortgage rates are therefore uniquely politically sensitive, in a way that other forms of debt are not. Normies don’t actually care what 10-year government bond yields do; they do care about the cost of their mortgage.

This raises the question: Will the threat of an impending housing crisis reveal a self-correcting political economy? Will central banks be able to continue raising rates despite the pain that this causes, or will central bankers flinch?

Wigglesworth asks whether we are about to enter, not the age of fiscal or even financial dominance, but what he dubs “mortgage dominance”, in which the sensitivity of over-borrowed middle-classes to higher rates puts a constraint on monetary policy. Wigglesworth cites several example from Scandinavia and Canada, where central bankers are already expressing concern about the impact of their tightening on policy.

But it is not Canada or Norway that sets interest rates globally, it is the Fed. And when it comes to mortgage finance the US is the exception. The state-subsidized 30-year fixed mortgage system in the US, backstopped by the so-called Government-Sponsored Enterprises, insulates the majority of US homeowners against any immediate hike in interest costs. This reduces the effectiveness of interest rates as a policy tool but also frees the Fed from “mortgage dominance”. Indeed, the Fed itself, thanks to years of asset purchases, owns a quarter of the mortgage-backed securities issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. All in all, the US mortgage system is something of a closed loop incorporating the finance of middle class home ownership onto the public balance sheet. In that system any losses from defaulting mortgages are ultimately covered by the public balance sheet and thus by taxpayers. But those costs are largely hidden from public sight and have far lower political salience than mortgage rates themselves. So unless the US housing market tips disastrously over the coming months, don’t expect political uproar to force the Fed’s hands. It will be the less-well protected homeowners in the rest of the world who will feel the brunt of the pressure.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I love sending out the newsletter for free to readers around the world. I’m glad you follow it. It is rewarding to write, but it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

There are three subscription models:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

To get the full Top Links and become a supporter of Chartbook, click here