Chartbook #162 In Memoriam: Bruno Latour

I fell under the sway of Bruno Latour in the early 1990s when I was a grad student at the LSE and I have remained under the influence of his thought ever since.

As much as I describe myself as a Keynesian or “left liberal”, I should probably add that I am a Latourian left liberal.

To be asked to write in Bruno Latour’s memory came as a shock. Not as a surprise - he had been gravely ill for a while - but as a shock.

First I needed arms around me.

Then I needed an idea. And that came with a tweet thread from Pierre Charbonnier, which ended with the appeal that after Latour’s passing our ambition should be to continue his project by continuing to press his questions on truth, modernity and ecology.

Thinking on Pierre’s appeal, what I realized I wanted to do was not so much to think forward from Latour’s death, but to linger with this event of his death and Latour’s own thought about life and death.

What did Latour write about death and life? The more I thought about it, the more redundant I realized the question to be. In a sense Latour’s entire body of work was about life. It was a Lebensphilosophie. But amidst the abundance of his writing I found the prompt I needed in a 2004 essay on “How to Talk About the Body? The Normative Dimension of Science Studies”.

You can read the resulting essay in the New Statesman.

By way of apology and with no false modesty I should add that this is not a piece of Latour scholarship. It is rather a personal response, by way of his work, to the crisis of his death.

Thinking about the piece took me back to a dinner with Latour in Paris in 2019 only weeks after Notre-Dame burned.

It took me back to our extended conversation about Carl Schmitt.

That conversation began in New Haven 2014 when I had the honor of introducing Latour as the Tanner lecturer.

In preparation for Latour’s visit, the philosophy of history reading group that I helped to organize at Yale had spent a term devoted to Latour’s magnum opus, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence.

In edited form, my introductory remarks for Latour’s lectures were these:

****

Words of Welcome for Bruno Latour

Tanner Lectures, Yale 26 March 2014

Adam Tooze

Stumbling into the second half of term last week, an announcement flashed up on my computer screen: “Award-winning sociologist to give Tanner lectures.” I must admit that it took me a few beats to realize that the email was advertising this wonderful occasion tonight.

It is not that our guest this evening is not award-winning. Of course he is. He has won many prizes. The Bernal prize in 1992, the Legion d’honneur, the Holberg memorial prize, to name just a few.

Nor is it that Bruno Latour could not claim to be a sociologist. In the breakthrough phase of his career he headed the lab at the École des Mines for the sociology of innovation.

But there was, nevertheless, in reading this email advertisement a moment of thought-provoking incomprehension, one of those category mistakes that are the driving motor of Bruno Latour’s most recent book An Inquiry into Modes of Existence (2012 French, 2013 English translation). The incomprehension arises from the yawning gap between what Bruno Latour’s writing has meant to us these last decades and that cookie cutter category of “award-winning sociologist”.

This evening, however, it is not the poor souls in Yale’s public affairs department who face the challenge of finding the right words with which to introduce our speaker, but me. It is not an easy thing to do. It is not easy because Bruno Latour’s influence has been so ramified. Because he is so generously prolific. There are so many “Latours”. But, above all, because if anyone has challenged us to think through the consequences of “fixing” or labelling language, it is Latour. Let me just take a recent quote :

“As I discovered many years ago in this very same laboratory at Salk, what makes scientific accounts so well suited for a semiotic study is that there is no other way to define the characters of the agents they mobilize but via the ACTIONS through which they have to be SLOWLY captured. Contrary to generals like Kutuzov (a references to Latour’s beloved Tolstoy, AT) and rivers like the Mississippi (as understood and fixed by the hydrological engineers), the competences of those agents discerned in laboratory experiments —that is, what they ARE—those competences come to be defined only long after by their performances—that is, by what they DO. … the dumbest of reader is able to imagine, no matter how vaguely, a Russian marshal or the Mississippi River by using his or her prior knowledge. But that’s not the case for as yet ill-defined hormone release factors. Since there is no prior knowledge, every trait has to be generated from some experiment.”

If you substitute for Russian Marshal “award winning sociologist” and for “ill-defined hormone release factors” the intellectual life force that is Bruno Latour , then you have a neat illustration of my problem in introducing our speaker tonight. Fix him and you lose him. Not that Bruno Latour is an enemy of all fixing. He is no luddite breaker of black boxes. No one has helped us more to understand the liberating power of such devices. As he will show in the lectures to come, there are two routes - one through semiotic analysis the other ontological – by which one might unpack the ways in which we institute the bifurcation between “what is animated and what is deanimated.” But let us not kid ourselves, when Bruno Latour gets translated into an “award-winning sociologist” something happens, a closing, a fixing, the rendering of something from a live force, an agent into a mere means.

So let us ask instead, what are the specific forces that keep him in motion? What does this agent, Bruno Latour, do? What effect does he generate? What drives his performance? Specifically in the last few decades? Because with a thinker as dynamic as Bruno Latour you have to run to keep up!

(1)

The most dramatic vector of this as yet unfixable agency is certainly the “great reveal”. Bruno Latour has gradually revealed to us and clearly laid out in his latest book that the “science studies Bruno Latour” of the 1970s and 1980s was always actually located within a vastly more capacious philosophical project that can be traced back to that protean moment in French thought in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the moment of Deleuze’s Difference and Repetition, the moment when the mid-career Foucault set out his differences with Derrida on the battlefield between Socrates and the sophists, in the first of the College de France lectures. From this moment Latour like some of his contemporaries, notably Bourdieu, unfolded a truly capacious project that was animated in Latour’s case by the most fundamental questions in ontology and drew above all on the inspiration of Charles Peguy’s early-twentieth-century thought. There were flashes of this in Irreductions the second part of the Pasteurization of France, but it now bursts fully into the sunlight in An Inquiry into Modes of Existence.

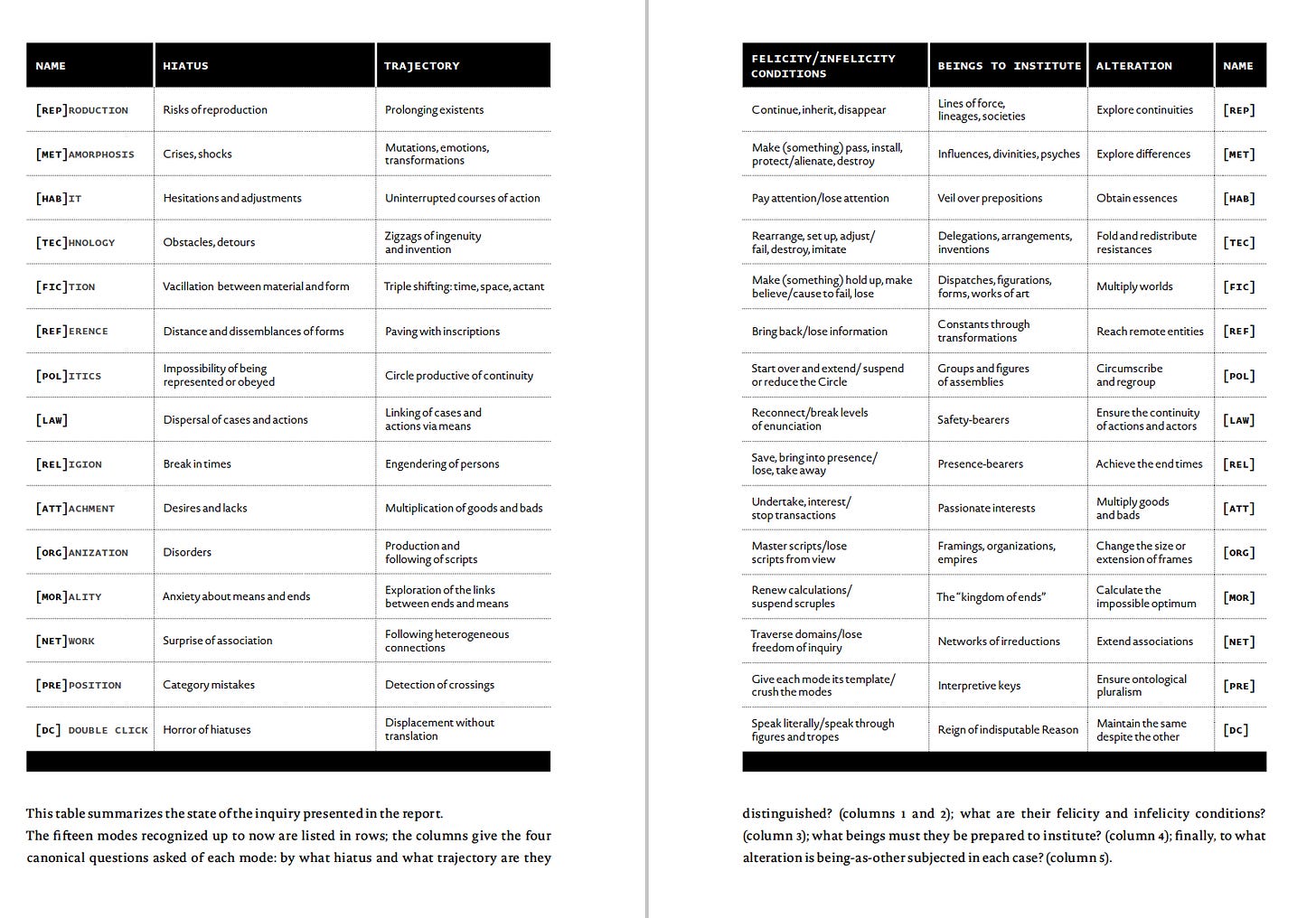

Latour’s enquiry into regimes of truth began with his Phd on biblical exegesis, by way of his experiences as a peace corps conscript in Africa and apprentice anthropologist to laboratory studies. Hermeneutics, anthropology and the lab formed a triangle. But Latour has now revealed to us that he always intended to move even further afield, beyond the laboratory to religion and further afield. The luxuriant proliferation of modes of existence, embracing, jostling in AIME is the working through of that original ambition. The number of these modes currently stands at 15, though Latour has suggested that this is a number contingent on the history of modernity and further to be elaborated in the collective project attached to the book.

The floor is open for more suggestions, to add further modes of existence to the list. The making of the list is in itself an irresistible impulse to creativity.

(2)

With this widening of scope has come not just a proliferation of fields, but also a new sense of emphasis. What has moved to the center is economics. Already hinted at in those passages on centers of calculation in Science in Action, but now identified as a central dynamic of the modern, threatening to overshadow all others. To which Latour characteristically responds not with defeatism or rejection, but with a dissection of the compacted incoherence of the field that we call the economic, into three separate realms of passionate interest, organization and accounting and equivalence-making.

(3)

And this focus on the economy gives us a third dynamic. Compounding the move to depth, to ontology, and the move to proliferation to modes of existence, we have a new burst of critical energy, how else to call it? I hesitate only because Bruno Latour is well known as a critic of facile critique. People have long struggled to place him. Is he a radical, a conservative? Perhaps what we realize now is that he is amongst our most articulate, most sophisticated defenders of liberalism. The re-appropriation of that old language, a characteristic move for Latour, is itself part of a constructive reconstruction. Liberal pluralism, he has announced, must be defended against its true antithesis, neoliberalism.

(4)

And Latour as critic is neither measured nor leisurely because in his recent work there is a fourth impulse at work: historical urgency. The advent of the Anthropocene has given a spectacular new urgency both to the philosophical project initiated in the 1970s and the day to day clinch with neoliberalism. The speed with which the environmental condition, the new sovereign, Gaia, has swept up on us, is one of its most awesome features. We are faced with a truly grim prospect: “No time for commerce. No time for solemn oaths.” Latour remarks, “Contrary to Hobbes’s scheme, the “state of nature” seems to have a dangerous tendency to follow, and not to precede or to accompany, the time of the civil compact. to talk of constitutions may come to seem like a strange form of nostalgia”.

What is Latour’s answer? A revival of the agora, a re-appreciation of politics and the political. Latour advocates a turn to Carl Schmitt, but shorn of the ruinous Wagnerian dramaturgy. Latour calls for a reexamination of the processes through which equivalences are made, not by some Smithian “invisible hand”, but through interested energized relations between actors of all kinds. And above all he demands a willingness to follow this through to its logical conclusion, a willingness to pose the question of the optimum, the question of the good, a moral question, understood not in Kantian terms as divorced from the world and its impulses, but on the contrary as inextricably bound up with it. This culminates in the extraordinary claim that the moral is a property of the world, or it is not at all. And a new definition also of the bad. Because it also in the world that the malign inversions manifest themselves that threaten any prospect of agency.

How then to respond? Characteristically, Bruno Latour is not afraid of heading back to the future. If the grandeur of constitutions eludes us at this moment of crisis, what option do we have? Latour’s answer is to take a stand on the institutions that give us some grip on reality. “Rebuild the institutions. To institute the values which we think it’s important to have.” And amongst those institutions, our own, the University is strategic. It is on the fault line within the University between the humanities and the sciences, facing as we now do common enemies in the perverse demands for financial and output accountability, that Bruno Latour will begin his talks this evening. I can’t wait. To have him with us at such a spectacularly fertile moment in his long career is a stroke of good fortune almost too sweet to believe.

****