It is the weekend of the eagerly anticipated Jackson Hole monetary policy conference. You can see the agenda, the papers and notes on the discussion here. Since the conference became a focal point of global monetary policy discussion, in 1982, it has not met under conditions as complex as they are today.

To mark the occasion Cameron Abadi and I did a podcast segment about the Jackson Hole conference for Ones and Tooze.

The Jackson Hole conference is different. It isn’t a jamboree like Davos, or a giant global gathering like the IMF/World Bank meetings in DC. Jackson Hole is an exclusive wonkfest attended by barely more than 100 central bankers, regulators, economists and handpicked journalists. The conversation is dominated by central bankers and the über-elite of academic economists who engage in friendly sparring over academic papers.

To get an idea of the crowd check out the roster of folks who attended the last in-person event prior to COVID in 2019.

How a conference of the world’s leading monetary policy thinkers and policy-makers ended up meeting in a mountainous resort in Wyoming, is an entertaining story nicely recounted in a short history put out by the Kansas City Reserve Board.

The fact that this world famous conference emerged in the late 1970s from a regional meeting on global agriculture, reinforces the point that the Kansas City Reserve Board is an idiosyncratic but fascinating vantage point from which to view world economic history. This was a point ably made by Leonard’s biographical study of Tom Hoenig, an obscure local economist who rose to be President of the Kansas City Reserve Bank and a major sparring partner of Ben Bernanke after 2008. I discussed Leonard’s book in Chartbook #85 earlier in the year.

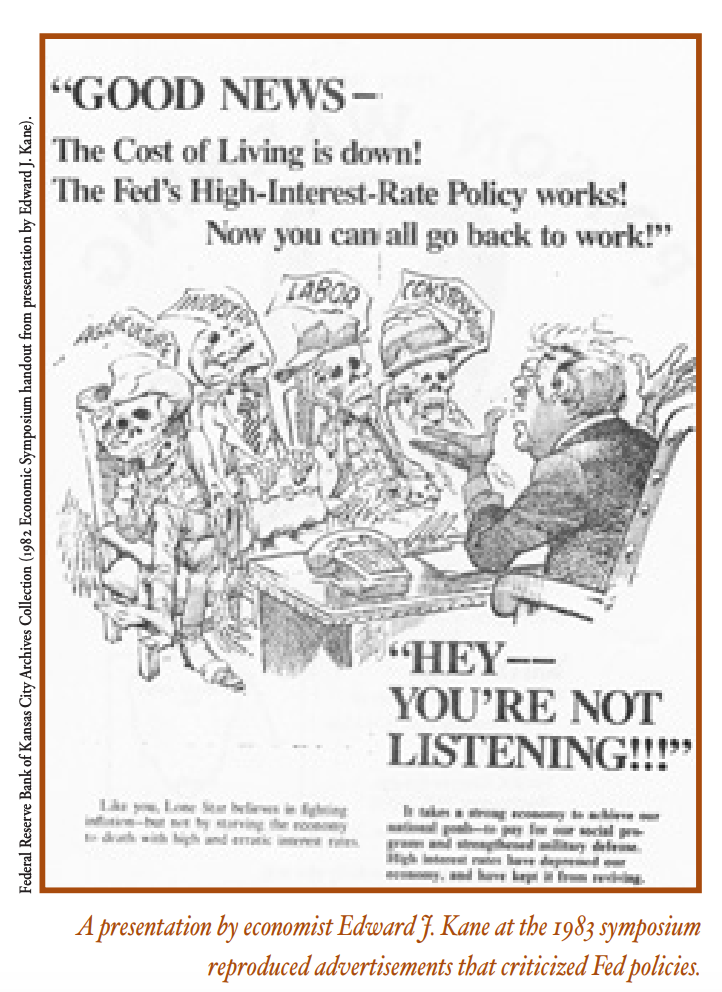

The first meeting attended by a Fed chair was in 1982, when Paul Volcker, lured to Jackson Hole by the fly-fishing, clashed with his Keynesian critics. Economist Edward Kane delivered a blistering critique of Fed policy backed up by amusing adverts being run at the time by America’s banks.

As the conference history goes on to note:

Although attendees would later note Kane’s presentation as being especially brutal and unfair towards both Volcker and the Fed, he was certainly not the only Fed critic in the room. James Tobin, a Nobel Prize-winning economist from Yale University, said during one of the symposium’s discussions that the Fed should have less autonomy. Monetary policy goals, he said, should be set in coordination with the government’s fiscal policy decisions. “After all, monetary policy decisions are the most momentous economic decisions the federal government makes,” Tobin said.4 “It seems anomalous to me that when the budget is planned and eventually voted, the process is completely detached from the gentle and amateurish surveillance the Congress exercises over monetary policy.” In case there was any question about Tobin’s views, the following Sunday, The Washington Post published a lengthy article by Tobin titled “Stop Volcker from Killing the Economy.”5

By the mid 1980s the Jackson Hole conference had firmly established itself on the circuit and journalists armed with the first generation of “laptop” computers were in eager attendance.

In doing research for the podcast perhaps the most remarkable piece I came across was an article by Brian Cheung on the community of Jackson Wyoming itself.

‘The weirdest place in the world’: What the Fed missed in Jackson Hole

Brian Cheung·Anchor/Reporter

August 28, 2019

As Cheung reported:

The Jackson Hole valley is home to the most unequal metropolitan area in the United States. As measured by the Economic Policy Institute in 2015, the top 1% of residents earned an average of $16.2 million, more than 132 times the average income of the bottom 99% of families.

It is a community divided between, on the one hand, the multi-million mansions of America’s elite, drawn to Wyoming by the scenery, the seclusion, and the great tax incentives, and, on the other, the service class of working people that struggles to find accommodation in the overpriced resort town. According to one resident, Jackson Wyoming is the “weirdest town” in America because you can always find work. You always earn well. But you always struggle to make ends meet.

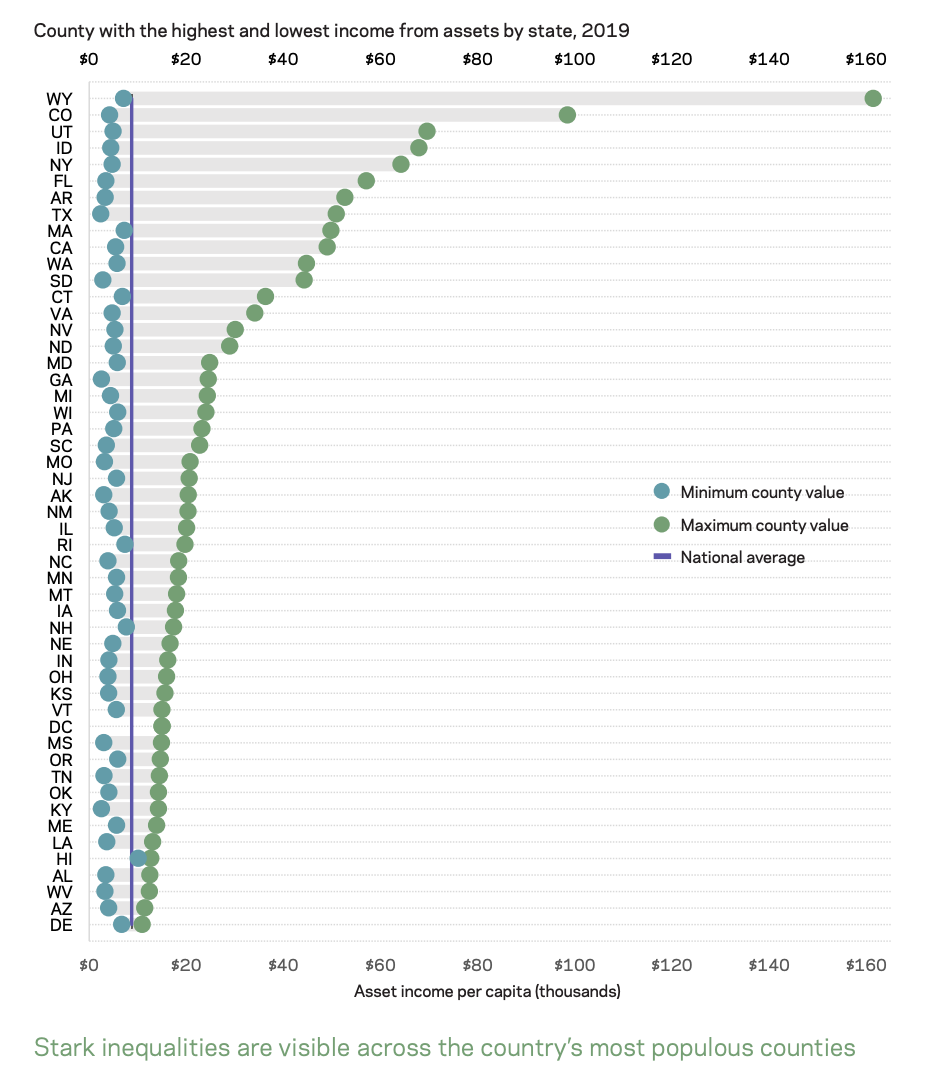

And these impressions were confirmed in 2021 by a study from the Economic Innovation Group which found that within Wyoming,

Teton County (Jackson Hole) is a preferred domicile of the super-rich and has the highest income from assets per capita in the country at $161,400, while Uinta County has just $7,100 per capita. As substantial as this gap is, Uinta is not far from the national average.

In 2022 all eyes were on Fed chair Jerome Powell as he struggled to define a new agenda for the Fed in the face of surging inflation. I did a piece for Foreign Policy in which I discuss Powell’s rather fascinating use of history in his speech to the Jackson Hole conference.

In my rather jaundiced take, Powell’s performance has about it an “18th Brumaire” feel - as in Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte - in which we go through the motions of reenacting Volcker’s 1979 interest rate shock, whilst being actually aware that conditions are radically different.

In his speech Powell’s use of history seems to have been quite self-conscious. In a piece by Colby Smith and Eric Platt one portfolio manager remarks:

“The theory of a dovish pivot has been squashed,” said Brian Kennedy, a portfolio manager with Loomis Sayles. “Powell is a creature of history and to me this is further confirmation that the Fed does not believe inflation is rolling over and going back to 2 per cent.”

As the FT spotted, Powell’s speech was studded with knowing references to the past.

Fed watchers noted that “Keeping At It” — a phrase Powell used twice in his speech — is the title of Volcker’s 2018 memoir, which was published just over a year before he died.

Meanwhile, as if to make my point, Bloomberg regales its readers with an entire battery of sensationalizing historical analogies.

The reality of 2022 is rather less dramatic than photos of the 1930s suggest. The Fed may be risking a recession as it tightens policy, but what kind of recession is it?

Economists also expect the US unemployment rate to rise beyond the 4.1 per cent broadly anticipated by Federal Open Market Committee members and regional bank presidents in June. The unemployment rate, a bright spot as the economic picture darkens, hovers at a multi-decade low of 3.5 per cent.

As is often the case, the smartest critical take on Powell’s dilemmas came from Mohamed El-Erian. Strikingly, El-Erian too framed his analysis in terms of temporality, in his case in terms of the past, present and the future. El-Erian was pleased with Powell’s message that rates will continue to rise and will do so for some time to come. But he regretted Powell’s failure to come to terms with the past and to more clearly map the future.

In El-Erian’s view, Powell has a fivefold problem.

(1) Powell’s 2021 speech premised on low inflation gave hostages to fortune and, with hindsight, was in El-Erian’s view a refletion of a fourfold failure of “bad forecasts, poor communication and belated policy responses”.

(2) In 2021, the Fed missed the chance for a soft-landing (by acting earlier) and now needs to show a determination to act since otherwise it will become a “mistake that builds on itself, aggravating problems of low growth, high inflation, worsening inequality and future financial instability”.

(3) The Fed’s forecasts and guidance have lost credibility. “Its quarterly (inflation) forecasts have been repeatedly dismissed as fantasy and its communication is seen as lacking the consistency needed for effective policy guidance.” This matters, according to El-Erian because it means the Fed will have a harder time persuading markets to believe its tougher stance.

(4) The Fed needs to address the fact that the “new policy framework” it first began developing in 2020 to deal with a world of low inflation, looks out of step with reality.

(5) Powell needs to “take responsibility for the last 18 months of Fed errors, including the mis-characterisation of economic and policy issues in last year’s speech”.

In El-Erian’s judgement, Powell’s unusually short 2022 speech: “dealt well with the present, but left out important past and future issues. I suspect that we will look back on this year’s Jackson Hole speech as a missed opportunity for the Fed to regain control over its policy narrative, as well as to outline what is needed to overcome the considerable policy challenge facing the world’s most powerful and systemically important central bank.”

This is perhaps the most substantive and extensive articulation of the critical position. It will be interesting to see how the Fed moves forward from this moment.

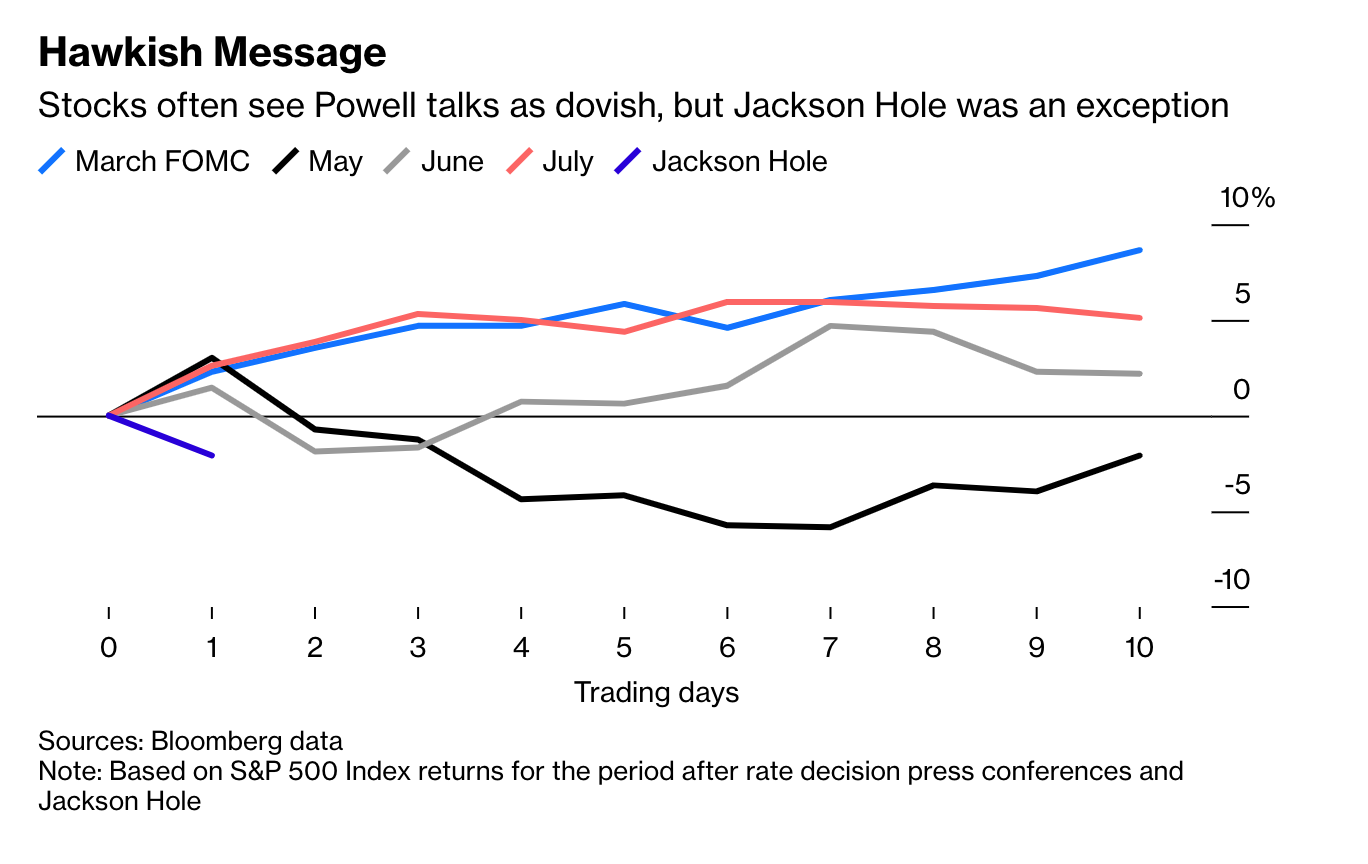

Not everyone agrees with El-Erian’s scathing critique. As Karl W. Smith notes at Bloomberg, the Fed has in fact pivoted to a far tougher line since March. Part of the problem is that after an initial selloff, markets have been slow to get the message. Over the summer the rebound helped to ease credit conditions at least somewhat.

On this occasion the markets seem to have taken the point.. Rather than rallying as they have done after Powell’s more upbeat press conferences, the reaction to his toughly worded speech at Jackson Hole was a significant sell off.

Meanwhile, Raghuram Rajan, formerly the governor of India’s central bank, is kinder to Powell.

Clearly the Fed’s shift in August 2021 to a more accommodating framework of average inflation targeting was ill-timed.

This was the right framework for an era of structurally low demand and weak inflation, but exactly the wrong one to espouse just as inflation was about to take off and every price increase fuelled another. But who knew the times were a-changing? Even with perfect foresight — and in reality they are no better informed than capable market players — central bankers may still have been behind the curve. This is understandable. A central bank cools inflation by slowing economic growth. No matter how independent it is, its policies have to be seen as reasonable, or else it loses its independence. With governments having spent trillions to support their economies, employment just recovered from terrible lows and inflation barely noticeable for over a decade, only a foolhardy central banker would have raised rates to disrupt growth if the public did not yet see inflation as a danger. Put differently, pre-emptive rate rises that slowed growth would have lacked public legitimacy — especially if they were successful and inflation did not rise subsequently. Central banks needed the public to see higher inflation to be able to take strong measures against it.

The real question is what happens next.

This is not a time for postmortems to assess central bank functioning.

Instead central banks in Rajan’s view should concentrate on inflation fighting and they should do so without fear of deflation.

Of course, when central banks succeed in bringing inflation down, we will probably return to a low-growth world. It is hard to see what would offset the headwinds of ageing populations, a slowing China and a suspicious, militarising, deglobalising world. … What if inflation is too low? Perhaps like the virus, we should learn to live with it.

Rajan’s worry is that if they go beyond this limited but cruciual mandate, they risk a larger cycle of exaggerated expectations, disillusionment and delegitimization.

As central bankers meet in Jackson Hole, they must wonder how far they have fallen in the public’s eyes. A short while ago, they were heroes, supporting feeble growth with unconventional monetary policies, promoting the hiring of minorities by allowing the labour market to run a little hot, and even trying to hold back climate change, all the while berating paralysed legislatures to do more. Now they stand accused of flubbing their most important task, keeping inflation low and stable. Politicians, sniffing blood and mistrustful of the power of unelected officials, want to re-examine central bank mandates.

It is a dramatic scenario, of which Rajan has some experience in the Indian context. And no one should underestimate the threats to the institutional fabric in America today. But here too one must surely ask, when the talk turns to “sniffing blood”, are we talking about reality, or are we enacting a pantomime political economy?

****

I love putting out the newseletter for free to thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

There are three subscription models:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

The thing to keep in mind is that Jay Powell was trained as a lawyer, and raised as a banker. The Fed--much like the medical profession--seeks legitimacy from science. But central banking is not economics, especially when embedded in a democratic polity. Expect the usual dose of miracle, mystery, and authority. This is not to blame the Fed--they're smart people who are trying to do their best solving problems that nobody really understands with a very limited set of intellectual and policy tools. I only worry about them when they start to believe their own bullshit.

Thank you for this summary and broader context! I had wondered why it was that they converged on Jackson Hole of all places, and who else attended.