Chartbook #128: Mission command - NATO's Strangelove vision of freedom enacted on the Ukraine battlefield

Russian forces attempted to cross the Siverskyi Donets river in eastern Ukraine this month using a pontoon bridge, but their tanks and armoured vehicles were picked off by Ukrainian artillery. So they tried it again. And again. And again. The Russian army made nine attempts to cross the river in the second week of May, according to Ukrainian defence chiefs. Russia lost about 80 tanks or other vehicles and more than 400 men in the ill-fated operation … It is part of a pattern of Russian behaviour since the invasion began three months ago. By contrast, Ukraine’s forces have proved to be agile, using the leeway afforded to company and even platoon commanders to shape their tactics according to the conditions on the ground.

Why have Ukrainian forces been able so far to withstand Russia’s assault on their country? It is a historic surprise a shock which offers a Rorschach blot onto which to project more or less ideological interpretation. In Washington in the spring of 2022 they have been summoning the Marshall Plan, Lend Lease and 1941. Classic Atlanticism in the form of NATO has made a come back. Weapons like the Javelin resonate with what Rayner Banham dubbed the “gizmo theory” of American power.

But it is reductive to explain Ukraine’s success through foreign aid, money and equipment alone. Against the odds Ukraine’s fighting forces are displaying remarkable resilience and skill. Ukraine’s soldiers appear to have absorbed experience from years of fighting in Donbas. But their success is also attributed, in much commentary, to military reforms introduced since 2014 under the influence of NATO. Western observers have seized on the contrast between the initiative shown by the Ukrainians and the dysfunctional repetitive behavior shown by the Russians on the banks of the Siverskyi Donets. For many observers it appears to confirm on the battlefield the cultural stereotypes of freedom versus disciplines that now associate Ukraine with the West against Russian “autocracy”.

This crude ethno-cultural distinction has a counterpart in technical military discourse. Whereas the Russians are laboring under rigid, top-down discipline, what Ukraine’s military have apparently learned from NATO is “mission command”.

In recent weeks, the FT, Economist and Atlantic magazines have all run stories attributing the Ukrainian military’s success to the adoption of the NATO practice of mission command. The Economist’s piece was written by no lesser figure than a former Ukrainian defense Minister, Andriy Zagorodnyuk". As he puts it:

Reforms in the Ukrainian army in recent years are now proving their worth, too. Many were inspired by the organisational structure of Western forces. One of the most important changes Ukraine made was to elevate the role of non-commissioned officers—senior enlisted men, like sergeants, who supervise troops—in the manner of NATO armies. This allows knowledge and skills to be passed on to soldiers. The Western principle of “mission command” has also been adopted by Ukraine’s forces. It allows the officers in charge of small units greater power over decisions, rendering those units more agile. The Russians have stuck with a top-heavy Soviet organisational structure instead.

Ben Hall, who wrote the description of the failed Siverskyi Donets river-crossing I cited above for the FT, lays out the argument in archetypal form:

Decentralised mission command — following strategic objectives set by military chiefs while giving lower ranks tactical autonomy — is standard Nato doctrine. Ukraine’s forces began to study it after independence in 1991, but only embraced it after Russia started its separatist war in the eastern Donbas region in 2014. Kyiv adopted far-reaching defence reforms in 2016 and US, UK and Canadian forces provided extensive training. “We have a different style and Ukraine’s is pretty similar to western doctrine — the freedom to adapt and achieve the goals according to their understanding of the situation,” said Mykhailo Samus, director of the New Geopolitics Research network … “The Soviet model is to follow the exact written instructions of their commanders.” Blindly following orders from high command and persisting with failed tactics on the battlefield have been features of Russia’s full-scale invasion ….

For Hall and his Ukrainian interlocutors the difference is not just a matter of culture:

“For a Russian infantry officer the risk of being punished by his commander is much more significant than the risk of losing his men or being killed himself,” said Oleksiy Melnyk, a former Ukrainian Air Force officer who spent 10 years under Soviet command. “If you see this order is a way to disaster, you have to tell your commander. That is what Russian officers are afraid of the most.”

By contrast, Ukraine has adopted a Western military style that focuses on empowerment, decentralization and even entrepreneurial virtues:

… Ukraine is building a corps of non-commissioned officers, corporals and sergeants who can make tactical decisions on the battlefield and are regarded as the backbone of western armies. … Ukraine’s military retained some of the culture of the volunteers battalions created hastily to defend the country in 2014 and subsequently incorporated into the army and national guard. “Many of them were formed and structured almost like civilian companies or non-governmental organisations,” he said. “They didn’t pay so much attention to military rank but to people with real leadership skills who could take command.”

Since the 1980s, “mission command” has, indeed, been a key element of NATO doctrine. It is commonly seen as a way to harness the freedom and initiative of fighting forces and thus easily segues with broader notions of Western culture and individualism. But where does this idea of “mission command” come from? What kind of “Western” idea is it?

Amongst NATO forces the first to adopt the term “mission command” or “mission tactics” were American marines and then the American Army in the 1980s editions of the basic field manual, FM 100-5. As was acknowledged at the time, the phrase is not originally English. “Mission command” is a loose translation of the German concept of Auftragstaktik. Its introduction to US and NATO doctrine was the fruit of the intensified interaction in the 1970s and 1980s between the US Army and the Bundeswehr in West Germany.

Opening the door to this intellectual transfusion was the work of an entire generation of officers and military intellectuals who shaped the US military and strategic debate down to the recent past. It involved agencies like US Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), successive editions of FM 100-5 and a bevy of defense intellectuals like William S Lind, war-gamers and military consultants. The process of trans-Atlantic transfusion generated its own hew histories of modern warfare. And it has since become the object of a cottage industry of commentary. A hundred years after Daniel Rodger’s famous trans-Atlantic progressive dialogue, this was another Atlantic Crossing.

I became fascinated with this military-intellectual nexus because it so clearly shaped the military history around which I fashioned the narrative of Wages of Destruction. The latest and perhaps most comprehensive revisionist history of this period was published in 2021 by Stephen Robinson, The Blind Strategist. John Boyd and the American Art of War. A highly recommended read!

John Boyd was a former fighter pilot who became a defense guru, pedaling lessons in a legendary slide pack which by the end of his career had extended to 1500 slides and presentations that could run to 13 hours straight. Robinson’s title is arch, because the contention of Boyd and his cohort was precisely that there was no such thing as an American art of war. Art is what America military history lacked. It had to be created by borrowing from the Europeans. And this is where the explosive story behind the concept of “mission command” begins.

The open secret amongst military experts is that NATO’s “mission command” concept so widely touted as a precious gift from “West” was, in fact, taken directly from the German military tradition and most immediately from Hitler’s Wehrmacht. And, rather than there being any contradiction, it was in effecting the transfusion from the Wehrmacht to NATO that the military idea of mission command/Auftragstaktik was bracketed with more wide-ranging notions of Western culture, individualism and freedom.

Already in the 1950s the Americans had relied heavily on lessons to be learned from Wehrmacht. Under the leadership of Franz Halder, chief of Army staff under Hitler, the German Military History Program rewrote the Wehrmacht’s World War II combat history for purposes of incorporation into NATO doctrine. For a brief period in the early 1950s NATO envisioned a mobile defense against the Warsaw Pact on the lines of the Wehrmacht after 1942. When the Military HIstory Program was wound up in 1961 President Kennedy awarded Halder the United States Meritorious Civilian Service Award for ‘a lasting contribution to the tactical and strategic thinking of the United States Armed Forces’.

But at that point the actual influence of German military traditions on the US military was at a low point. In the mid 1950s, under the sign of the new generation of thermonuclear weapons, thinking about mobile conventional warfare on the battlefield of West Germany was displaced by all-out nuclear deterrence. By the 1960s America’s own military leadership style was managerial rather than military in the classic sense. McNamara and the Pentagon’s efforts at top-down control in Vietnam exemplified this firepower and bodycount centered vision of warfare. In that conflict it was not even obvious whether there was any room for tanks to be used in earnest.

It was the humiliating withdrawal from Vietnam and the new focus on NATO’s central front in West Germany in the 1970s that sent the US military, and most importantly, the army in search of a new way of thinking about war. On the central front in West Germany, unlike in Vietnam, NATO’s forces would expected to be massively outgunned. They would need to develop a new repertoire of military skills and artistry if they were to prevail.

From the late 1960s the Warsaw Pact undertook a considerable modernization of its conventional forces and appeared to be preparing in the words of Donald Rumsfeld in his Annual Defense Department Report of 1977 for a “relatively prolonged conventional campaign” to precede any use of nuclear weapons. Systematic upgrading of Soviet conventional forces symbolized by the new generation of T72 tanks, meant that technological parity now compounded the obvious numerical superiority of Soviet force. Furthermore, the Israeli encounter with Soviet anti-tank guided missiles in the hands of Egyptian troops in the Sinai in 1973 and the blazing intensity of the defensive battle in the Golan suggested nothing less than a revolution in modern weaponry.

If it was to hold the line, NATO would need to fight like the US army had never fought before. There was no room to retreat and no giant reserves of strategic power to draw on. If one wanted to avoid escalation to full-scale thermonuclear war, NATO would have to try to win the first battle in Germany.

Andrew Bacevich, who was serving with the US Army in Germany in the mid 1970s, puts it eloquently in The New American Militarism. In the wake of Vietnam and the moral confusion of Watergate he remarks “…inside the cocoon of military life, there existed one fixed point of absolute and reassuring clarity. Those of us whose day-to-day routine centered on furiously preparing to defend the so-called Fulda Gap, the region in western Germany presumed to be the focal point of any Warsaw Pact attack, had no need to torment ourselves with existential questions of purpose … our purposes was self-evident: it was to defend the West. … here was the lodestar … this was what we understood to be the American soldier’s true and honourable calling.”

It was not just a professional and moral challenge. It was also cognitive. Analysts like Steven L. Canby a reserve army colonel, and partner with Edward N. Luttwak in C&L Associates railed against the Pentagon planners and their one-sided focus on firepower and a methodology that was mechanical and arithmetic. Canby rejected “Lanchesterian firepower models” and NATO’s addiction to a “systems approach to analysis”. He had nothing but scorn for the “civilian leadership and analytic community” relying on a “methodology independent of substantive knowledge of the subject field … a methodology based upon constrained maximization but unable to define an effectiveness function”. At NATO HQ, military analysis had been reduced to an exercise in “cost minimization and a transnational comparison of inputs”. What Canby, Luttwak and their colleagues in the military reform movement like William S Lind wanted to bring to the fore instead was history, military art and maneuver. Some, like Luttwak, stressed the operational level of war - between strategy and tactics. Others focused on the practices that enabled European militaries and the German militaries in particular to fight war. One key concept was Schwerpunk, the decisive point of attack. Another was Auftragstaktik, what would later be dubbed “mission command”.

In the neoliberal parlance of the day, American commentators translated this into a contract by which “The subordinate agrees to make his actions serve his superior’s intent in terms of what is to be accomplished, while the superior agrees to give his subordinate wide freedom to exercise his imagination and initiative in terms of how intent is to be realized.” Finally, the soldier would be free on the battlefield to accomplish his mission undirected from above. All his faculties would be engaged towards the common end. His subjectivity restored.

The appropriation of German military history thus served a deep purpose in America’s culture wars of the 1960s and 1970s. Auftragstaktik, mission command, was the gothic scissors that cut through the threads that suspended the American fighting-man like a puppet from the dead hand of Mcnamara’s Pentagon.

Auftragstaktik was not invented by Hitler’s Wehrmacht. Anglo-American histories of the term, of which dozens circulated in professional circles, would generally trace the idea back to the age of the legendary chief of staff Helmuth Moltke and his emphasis on the need to adjust war planning to particular circumstances and contingencies. A specifically tactical meaning of the term began to take shape in the later stages of WWI in the “Sturm” tactics adopted by the crack units of the German infantry to mount their final wave of offensives against the trench lines. Figure like Ernst Jünger or Erwin Rommel exemplified the new model of highly motivated, intelligent and independent battlefield leadership. By the 1920s the Reichswehr had become to distill some of that experience in its new manual on Truppenführung (troop leadership).

It was attractive for America’s military reformers in the 1970s to trace the concept of independent decentralized leadership to roots in the 1920s. Finding the idea in the Weimar Republic avoided the odium of association with Nazi Germany. Furthermore, embattled advocates of a new American militarism, could identify with the Reichswehr military commanders who in the Weimar Republic sought to preserve a state within the state, much as Samuel Huntington imagined the American army as a society and polity apart. But the Weimar Republic’s Reichswehr was an army that never fought a war. Its real historical significance is that it served as a vehicle for the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany.And it was from in-depth study of the Wehrmacht, through cooperation with the Wehrmacht’s successor, the Bundeswehr (which was going through its own process of incorporating its military history) and through actual encounters with surviving Wehrmacht veterans that a new model of war was transferred to the US Army in the late 1970s and 1980s.

This convergence between US Army and Bundeswehr thinking was encouraged by Chief of Staff General Abrams, and was eagerly taken up by TRADOC commander and World War II veteran General William DePuy eagerly followed the hint. He was followed by General Don Starry commander of V Corps in West Germany and later head of TRADOC. The US-German synthesis had close synergy. When General Alexander M. Haig Jr., the new supreme allied commander, Europe, expressed to General DePuy his reservations about the emerging doctrine, DePuy countered that Haig was "ignor[ing] the German origins of a great part of that doctrine" and advised him to "be aware of its almost total coincidence with that of our German allies." The new 1970s version of US Army Field Manual 100-5 was written in close collaboration with the armoured infantry experts at the Bundeswehr tank school who were at the time developing an updated model of the wartime Panzergrenadier (armored infantry), which would become the standard divisional unit of NATO forces by the 1980.

Timing matters. This German-US transfusion took place not back in the 1950s in the immediate aftermath of World War II, but in a belated return to history in the 1970s and 1980s. This means that the practical influence of lessons learned from the Wehrmacht on the US and NATO reached its height precisely when the wider historical and political debate about the Wehrmacht’s deep involvement in racial war was beginning in earnest. It was the same moment as the scandal surrounding Reagan and Kohl’s visit to the Bitburg cemetery. It was the same moment as that in which Habermas was fighting out the Historikerstreit over the resurgence of nationalist currents.

As Robert M Citino puts it, “in the years after 1982, it became difficult to pick up any American military journal without reading something about the German army.” The German fashion amongst America’s military intellectuals ticked all the boxes. As Michael Swain notes, “the young authors achieved the tone that their generation looked for, a style of war marked by the offensive, maneuver, and surprise – with due attention paid to human as well as material factors of battle.”

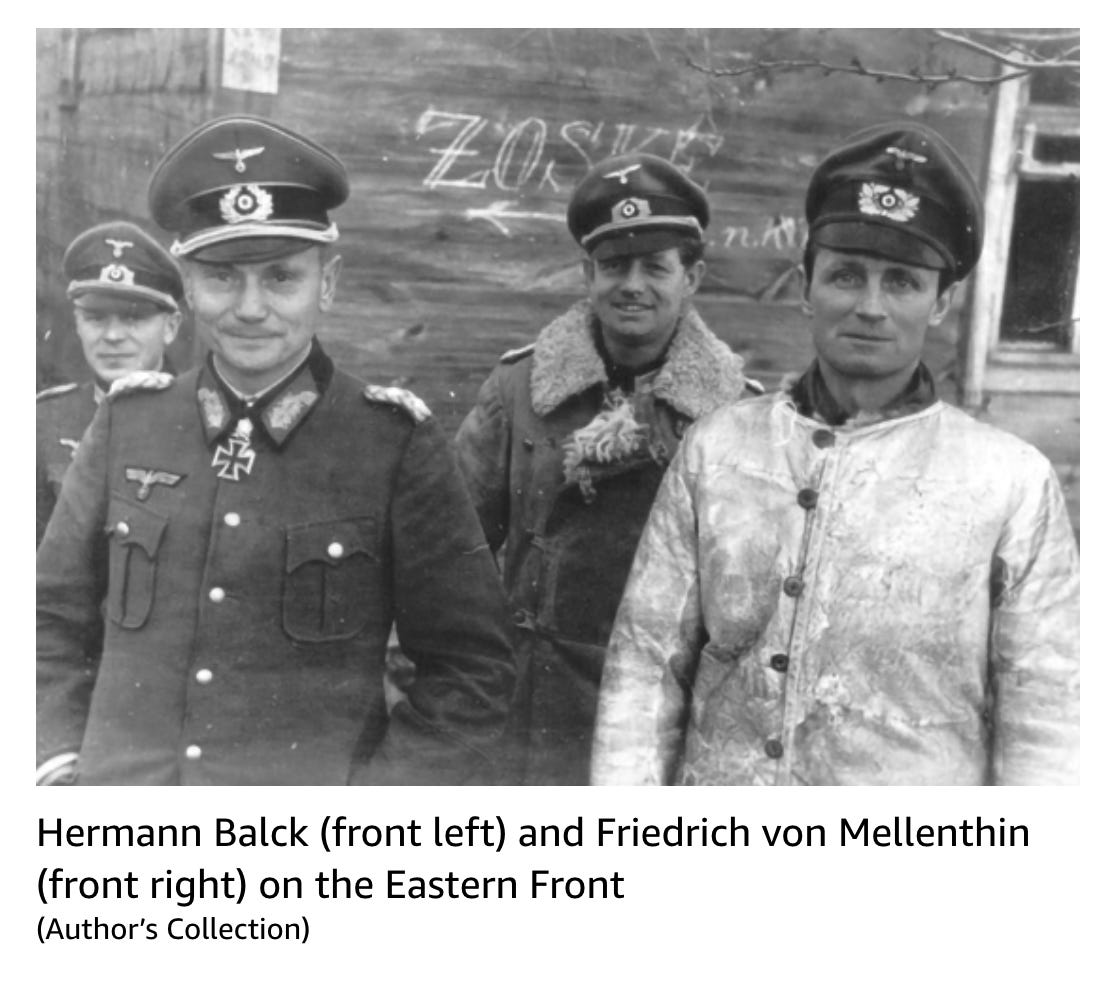

Indeed, the American military were not content with merely reading history they wanted to experience it up close. In May 1980, at one of the military-industrial facilities that dot the beltway of Virginia, history was brought to life. The host was the BDM Corporation, a favoured consultant to the Pentagon, and war-gaming outfit SPIT. The sponsor was Andrew Marshall of the Office of Net Assessment. The rapporteur was General DePuy, recently retired head of TRADOC. The audience included a nameless group of the more intellectually-minded officers of the US Army. But the stars of the show were the foreign guests, two spry, elderly German gentlemen, General Hermann Balck and his former Chief of Staff General von Mellenthin.

Picture: Stephen Robinson

Since the stars of the postwar Blitzkrieg circuit notably Guderian and Halder had died, the American military reformers were now drawing on the second tier. Thanks to his bestseller Panzer Battles Von Mellenthin was a global miltiary history celebrity. But Balck, the senior of the two, was the real sensation. He had held back. Refusing to cooperate with Halder he now found himself at the cusp of the next graph phase in the Cold War as the senior surviving panzer general.

Their combined battlefield record was second to none. But what was less often noted was that Balck had reason to lie low. As a Wehrmacht officer General Balck displayed a gung-ho attitude that had alienated even the Waffen SS during the prolonged and bloody defensive battles in Hungary. In 1947 Balck was convicted by a German court for the murder by firing squad of one of his subordinates to whom he had not even extended the perfunctory court proceedings provided by Nazi military law. He served half of a three year sentence. He was also convicted by a French military court in Colmar to 20 years of hard labour for his role in the scorched earth Operation Waldfest but was never extradited

In the United States in 1979/1980 Balck found himself lionized. And he delivered preicsely what the Americans wanted, an authentically European view of military leadership, presonalistic, dynamic, but not based on technology. To illustrate this point at his own expense John Boyd the marine corps guru liked to tell the story of how during a dinner party he had sought to compliment Balck by suggesting that with his lightening fast reactions he might have become a superb fighter pilot, Balck snapped back: “I am not a technician”.

At the war game in Virginia the attention of the observers was divided between the specifics of the maneuver in which an American solution was contrasted with the solution developed by Balck and von Mellenthin and the more general issue of command style.

As far as the war game itself was concerned, the Germans performed true to type. The challenge, inevitably, was to defend the Fulda Gap. And after only five minutes of urgent discussion the Germans decided that rather than doggedly defending the forward end, as prevailing NATO doctrine would demand, they would entice a Soviet armoured thrust all the way to the outskirts of Frankfurt, before delivering a massive counterblow. Military artistry would allow disproportionate effects to be achieved even with inferior forces. But beyond the maps, what fascinated the Americans was actually to witness these two veterans of German command style close up. General William DePuy made a point of writing up the report himself and first on the list of “interesting themes” to emerge from the four day conference he put quite simply “General Balck and von Mellenthin themselves and their relationship to one another.”

As DePuy went on in a gushing tone: “Those readers who may not have studied the background of the distinguished German participants might not appreciate the full authority with which they speak – authority growing out of an incomparable set of experiences in war against Russians a record of battlefield performance unsurpassed anywhere in the history of modern warfare. … the character and personalities, as well as the personal relationship between these officers, were fascinating and compelling.” Succumbing quite uninhibitedly to the desire for inclusion in the charismatic circle, the preface to the report considered it necessary to add to the short biography of DePuy, a four star general, former vice chief of staff and commander of TRADOC, the tell tale observation that “Balck and von Mellenthin’s respect for General DePuy was evident in their reference to him as a “kindred spirit”.

The Germans were good cop-bad cop buddies of hard-boiled cliché. “General Balck tends to be a man of few words – somewhat brusque almost laconic but deeply thoughtful. He was, and is, clearly a man of iron will and iron nerves.” “Von Mellenthin by contrast was a “more gentle officer on the outside. However, his record and Balck’s esteem tell us that he is also a man of steel at the core.” Twenty five years after the end of a lost war, Balck still exuded “a strong aura of confidence – confidence in himself, in the German Army and in the German soldier. He has no doubt about the superiority of the German over the Russian …” By the fourth day of proceedings “when a large number of interested observers” attended the final session the tone of lacerating self-criticism on the part of the Americans was overwhelming. As DePuy reported “invidious comparisons were being drawn between German and US Armies to the effect that the German leaders were uniformly superior in battlefield tactics. The patent excellence and superb performance of Generals Balck and von Mellenthin … led the audience easily in that direction.”

In an illustration that borders on the parodic, the Army’s leading periodical Military Review actually created a cybernetic model that contrast the remarkable lightening fast, 5-minute decision-making process exhibited by Balck and Mellenthin with the ponderous 14 hour cycle more normal in the US command chain. At the ages of 87 and 76 respectively, Balck and Von Mellenthin were 150 times faster than the standard NATO decision loop.

But the truly telling point was that as far as the Germans were concerned, the entire encounter rested on a misunderstanding. The Americans, with their essentializing reading of the difference between US and Wehrmacht military culture was missing the point. To be more precise. The Americans had hold of the wrong essentialism. For Balck and von Mellenthin far from there being a gulf that separated them from their hosts the more important fact was that Germany and the US were both part of the “West” and exponents of a culture of individualism and this distinguished them both from their potential enemies.

When asked to comment on the rigidity of Syrian offensive formations in the Golan battles of 1973 and possible similarities to Red Army practice, Balck responded with the following bizarre outburst: “Normal European and American countries educate their peoples like we do. There is a different class of prairie people – prairie nations like Hungary, like some peoples in Asia. They are used to flat, open terrain, and they use this kind of attack … then there is a third category: mountain people. They adapt more to the features of terrain. … Prairie people should not be used in modern warfare because that courts disaster.” General DePuy though himself a native of the prairie-state North Dakota did not even flinch.

Balck’s assessment of the Syrians was fully in line with his similarly contemptuous judgement as far as the Soviets were concerned. For Balck and von Mellenthin the German style of warfare was not just a tool that needed to be adopted to bolster NATO, but was nothing less than an expression of the best values of western civilization: intelligence, initiative, mind over matter. According to Balck and von Mellenthin far from being alien to the American mind, Blitzkrieg and manoeuvre warfare, founded as they were on freedom and intelligent individualism were expressions of a common Western civilization. By contrast, whatever technical improvements the Red Army might make, whatever operational skills its generals might possess and whatever fighting qualities were innate to the Russian serviceman, they were forever excluded from the cultural heritage of the West.

As von Mellenthin put it “they are masses and we are individuals. That is the difference between the Russian soldier and the European soldier.” Viewed in these terms Auftragstaktik, mission command, was nothing less than the expression of the inner spirit of Western culture in military form.

If one took this at face value it had radical implications, some of which were teased out in later discussion. NATO’s new art of war could be expressed in a piece of equipment, like an American-German infantry fighting vehicle. Some thought the new convergence could be read off the strange convergence of US helmets with the “Krautpot” familiar from the Wehrmacht. It expressed itself in basic concepts of leadership like “mission command”, but also in operational designs.

If it was true that West Germany was a nearly indefensible strip that did not permit large-scale maneuver operations in which the independence enabled by mission command would show itself to its best effect, then NATO should find a battlefield in which its natural cultural advantage would come to the fore. Samuel Huntington in an article in International Security in 1983 argued that rather than hunkering down in the Fulda gap, NATO should play to its strengths. If the Red Army was indeed “better at implementing a carefully detailed plan of attack than they are at adjusting to rapidly changing circumstances”, the argument popularized by von Mellenthin and Co, then NATO should respond with the ultimate surprise. Any immediate threat of Warsaw Pact assault across the North German Plain should be met by a NATO counter-offensive into East Germany. Of course, NATO would be at a numerical disadvantage. But as the German triumph in 1940 demonstrated one did not need overwhelming material superiority to win a decisive military victory. With the main bulk of Warsaw Pact forces concentrated in the North, NATO spearheads should drive out of the Hof corridor towards Jena and Leipzig and through Czechoslovakia towards Dresden or Prague. It was Manstein’s famous scything blow through the Ardennes, in mirror image. It would throw the Warsaw Pact off balance and give free rein to Western initiative and freedom to carry the day.

Mercifully, NATO never got to test that theory of war in an actual clash with Soviet forces. Instead, the new mode of war was enacted in 1990-1991 in the devastating riposte to Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait. For the generation of American military leaders headed by Powell and Schwartkopf this was the vindication of the entire reform program of the 1970s and 1980s. They had learned their lessons well. But had they really? As one TRADOC historian admits. Desert Storm was “a bit of a historical anomaly:” “It is a rare event for an operational plan to play out as designed.” The plain truth was that in Moltke’s term there had been no enemy “main force” to encounter in Kuwait, an obstacle the encounter with which might have provided a real test of military leadership and skill. The American and Allied troops ploughed across desert as if engaged in a particularly undemanding war game.

This gives to the battle in Ukraine a peculiar historical significance. If Ukraine’s forces really are influenced by the “mission command” model they have learned from NATO this is in fact the first time it is being put to the test against the original intended enemy and in the kind of life-or-death battle that NATO envisioned in the 1970s and 1980s.

But this poses tricky questions. What is the appropriate way to think about the relationship between military and political culture? What are we to make of this twisted genealogy of NATO’s idea of freedom?

In the 1980s the obvious move to make was to argue that the appropriation of military techniques from the odious Hitlerine regime was legitimate so long as military techniques and deeper political values were separable. But that is not the claim currently being made in Ukraine. Instead the association is constantly being drawn. Ukraine’s freedom and initiative on the battlefield are being contrasted to the robotic performance of the Russians. This undeniably converges with the argument made by Wehrmacht veterans like Blank and von Mellenthin in ingratiating themselves to their American acolytes. They too thought of the German way of war as an expression of deeper, common Western values.

There are two ways out of this trap.

One important point of difference is to guard against ethno-cultural determinism. The story told in Ukraine is one of learning, across cultural and social divides. After all, only recently, Ukraine’s military were post-Soviet too and they have been coached to fight differently. Contrary to the Balck von Mellenthin version, there is no good reason to imagine that Russians could not learn the same lessons if their regime would let them.

But secondly and more importantly, it is a fatal trap to align different notions of individuality and freedom. It may well be true that success in intense modern combat requires not just courage but a certain sort of initiative, a certain kind of freedom. But let us not confuse those expressions of agency, and initiative, with other broader notions of freedom that we employ in political or cultural thought. The battlefield is a zone of absolute and violent constraint. As Clausewitz says the enemy gives me the law. To prevail may require a sense of super human strength or extreme self-sacrifice. Furthermore it requires one to regard the enemy as a counterpart not to be reasoned or bargained with, but to be outwitted, crushed and if necessary incapacitated or killed. All this may be necessary for success. But we should not confuse freedom as life and death struggle with the ideals we cherish as democracy or in visions of free society.

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

A whole lot of "extrapolation" from one military blunder. playing into the pre-conceived stereotypes of "western agility" vs. "eastern rigidity". The failed crossing of Seversky Donetsk was much discussed as an exemplary failure of command in Russian Telegram channels (behind some of which are some very well informed and connected military persons), but it is an exception that proves the rule - in this war the Ukrainian side has been the rigid and inflexible one (dig in, defend anything to the point of encirclement and annihilation), while the Russians moved and maneuvered over a 800km length of battlefield, changing axis of attack and intensity many times.

The results are slowly becoming visible - the Ukrainians are losing the war.

Why do people believe this obviously biased Ukrainian view of what happened at that river crossing? The Russians are clearly winning the war and the Ukrainians have not shown any special "agility". There is a reason why Ukraine release no information on casualties. Just look at the maps (from Ukrainian sources) of where engagements are happening and it is very obvious that Ukraine is retreating everywhere. Believing propaganda can be very dangerous to the soldiers on the front lines.