Chartbook #112 Inflation is hurting, but will it last? Between normalization, Putin's war and China's Covid shock.

The current surge of inflation is having a painful impact on the cost of living especially for folks on below average incomes. The key questions are (a) will it last and (b) what can monetary policy do about it?

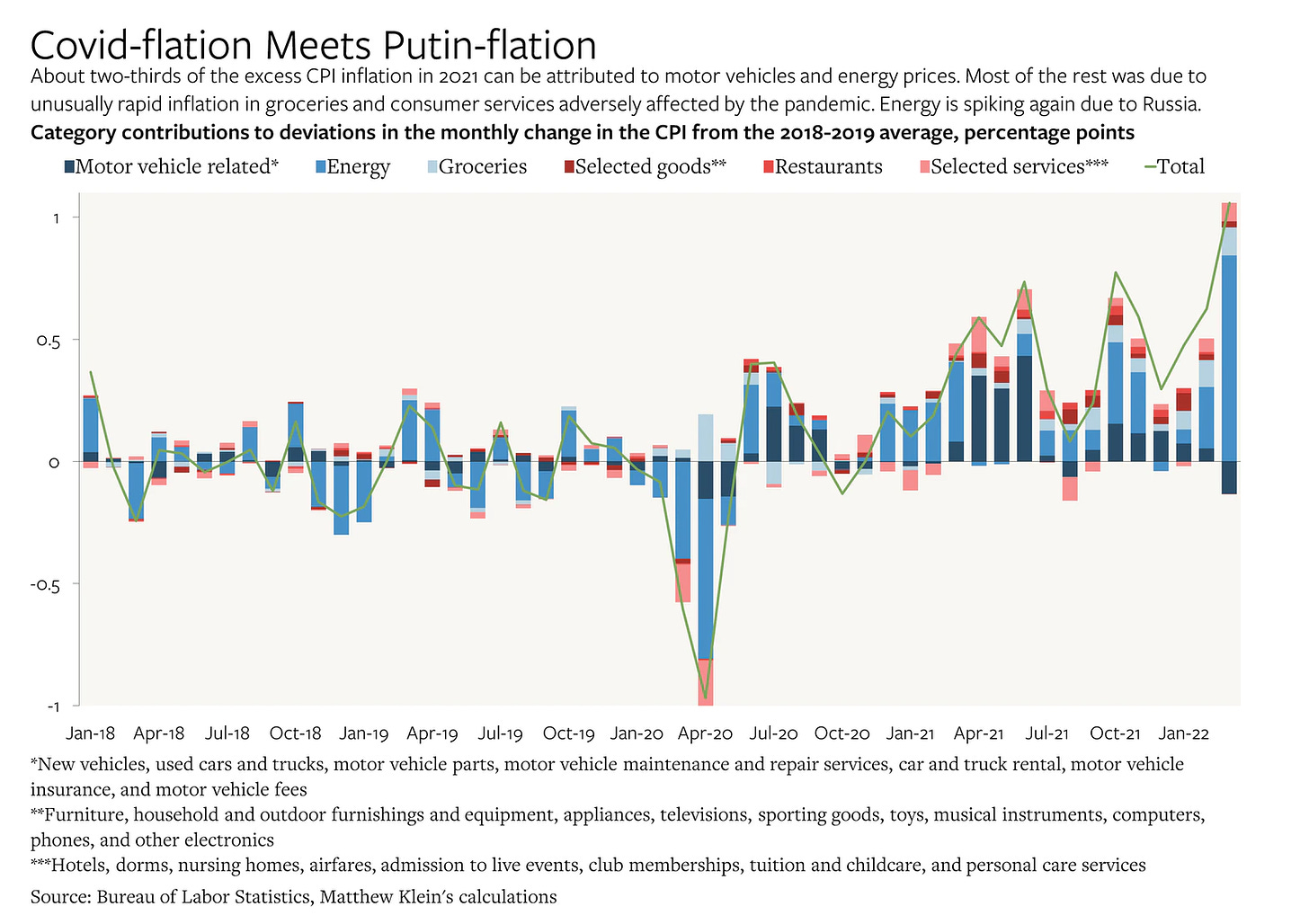

As Matt Klein makes clear in another excellent Overshoot newsletter, a variety of different factors are at work in the current situation. There is an energy shock, a China Covid-shock and a normalization of the world economy, all operating at the same time.

It is pricey, but if you can stretch Matt Klein’s newsletter does NOT disappoint. Highly recommended.

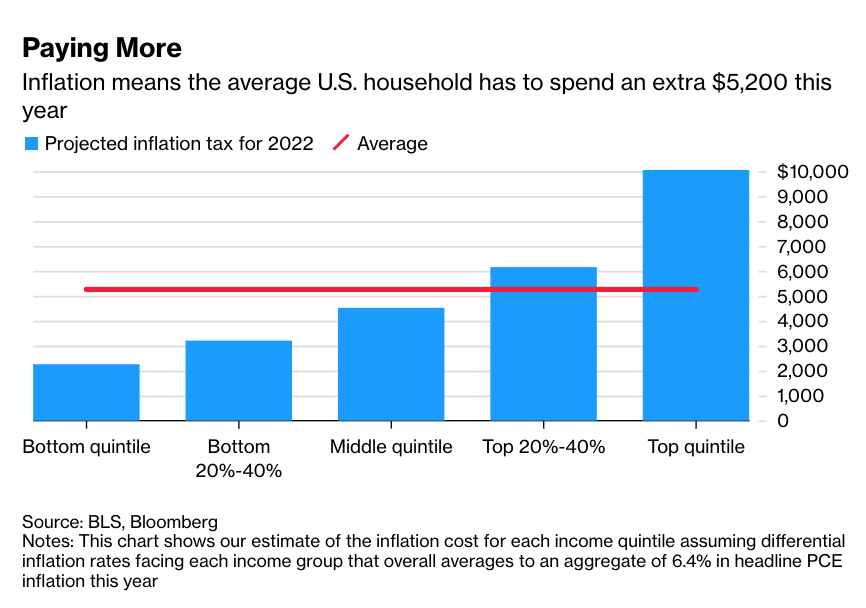

In the short-run the pain being inflicted by rising prices is all too real. According to a striking report over at Bloomberg by Andrew Husby and Anna Wong

Inflation will mean the average U.S. household has to spend an extra $5,200 this year ($433 per month) compared to last year for the same consumption basket, according estimates by Bloomberg Economics. The excess savings built up over the pandemic, and increases in wages, will cushion those costs, and allow spending to expand at a decent pace this year. But accelerated depletion of savings will increase the urgency for those staying on the sidelines to join the labor force, and the resulting increase in labor supply will likely dampen wage growth.

The percentage of Americans who expect to be worse off financially in the next 12 months hit the highest level in at least nine years.

Source: New York Fed via @soberlook

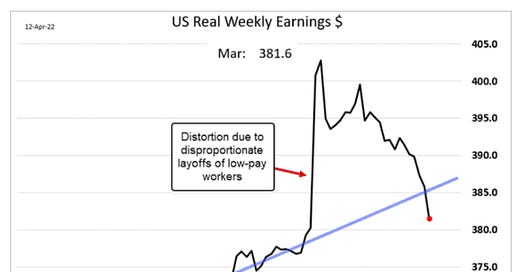

Those sentiment numbers reflect the hard reality that rising prices have been eating into whatever wage gains were made during the COVID shock and its aftermath. Real weekly earnings are now below their pre-COVID trend.

The source for this graph is The Daily Shot, another newsletter you should consider subscribing to if you are serious about following the markets. I love it for its breadth of coverage.

One thing these numbers tells you is that talk of a wage-price spiral is grossly exaggerated. Wages are not keeping up.

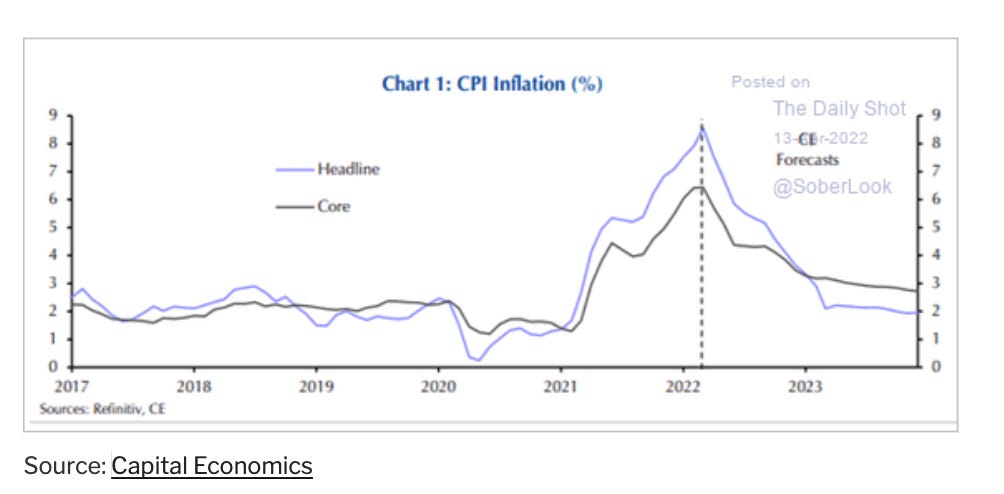

Furthermore, it remains true that though the headline figures are alarming,, most forecasters expect inflation in the US to ebb sharply and to fall close to 2 percent by the end of 2023.

We aren’t supposed to call this “transitory inflation”. So shall we call it a “spike”?

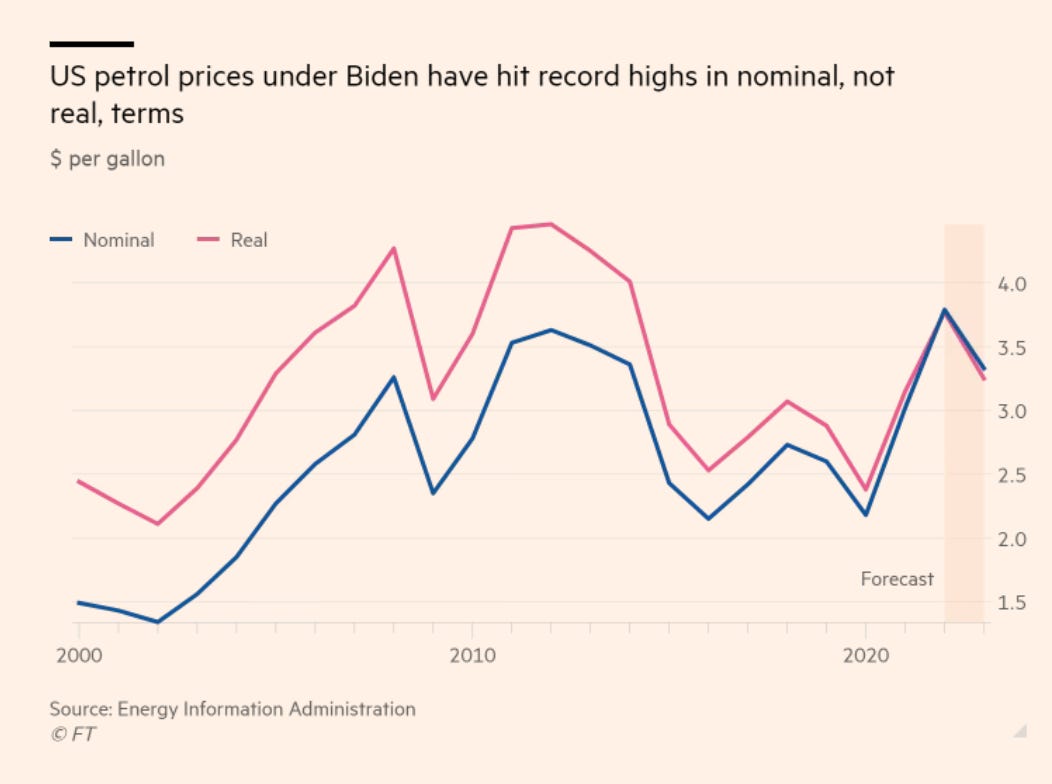

It is also important to remember that inflation rates are not the same as price levels. If you are the Biden administration facing the midterms in November, the surge in petrol prices is a nightmare. But once adjusted for general inflation, the current rate of petrol prices in the US, is still some way short of historic highs.

Source: FT

The evidence from the US price numbers suggests that apart from energy the other drivers of inflation may actually be calming. As far as energy is concerned, if Putin’s war pushes prices up, China’s COVID surge pulls them down. And in recent weeks it is the downward forces that have been winning.

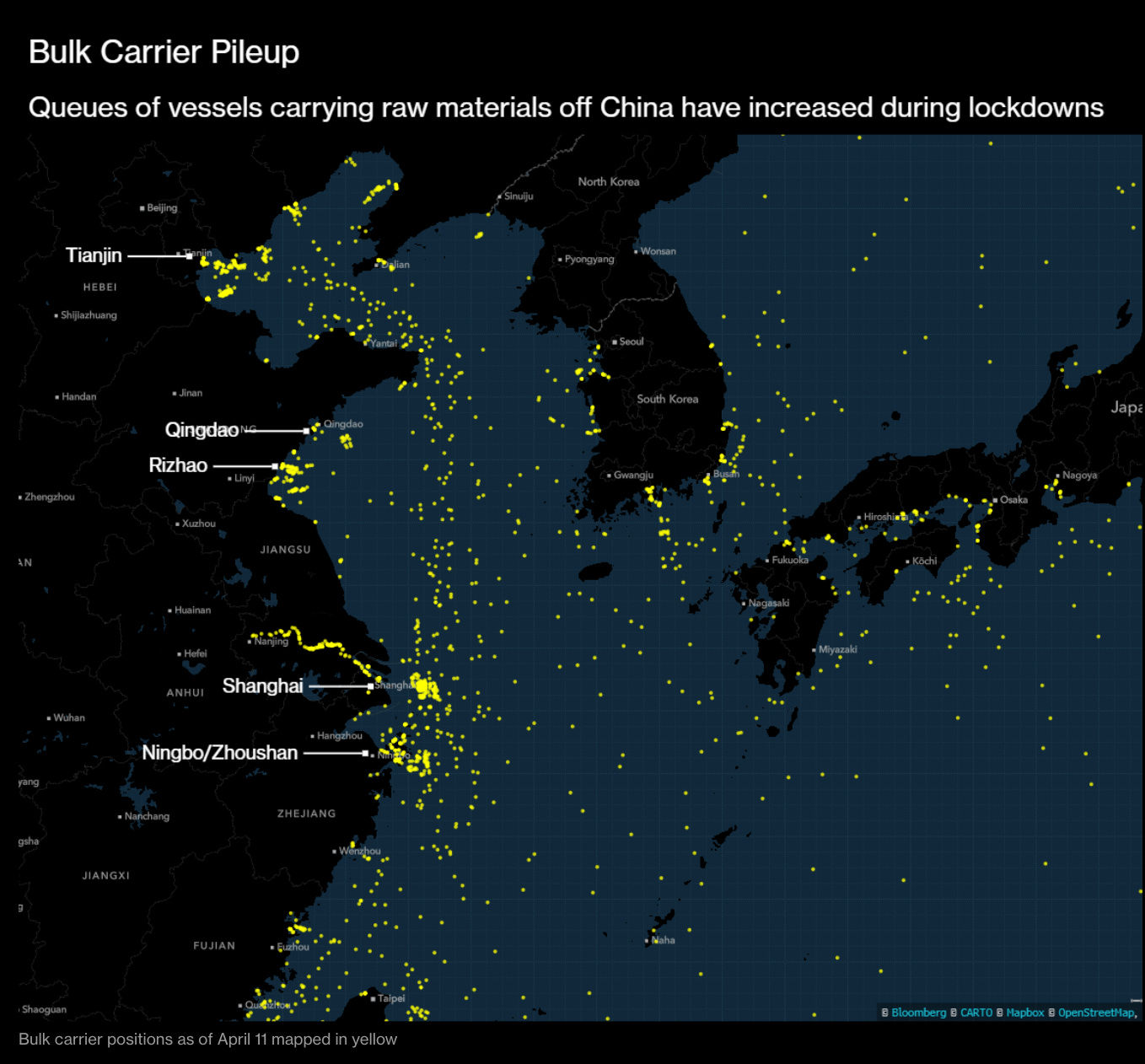

What about the lockdowns and supply-chain problems? They could certainly get bad! All eyes on Shanghai. This image from Bloomberg dramatically captures the pile up of bulk carriers off the Chinese coastline.

But as Claire Jones points out at FT’s reinvigorated Alphaville blog, shipping rates are actually coming down. Why? Most obvious answer is that the huge surge in demand for goods in the United States is cooling.

Shipping companies have begun to take an increasingly sanguine view of available capacity going forward.

Whether this lasts will critically depend on developments in China. It is hard to exaggerate the significance of the drama there, as Robin Harding points out in an excellent column.

So, we face serious inflation. It is eating into real incomes. What are central banks going to do? They are determined to raise rates. But will this actually help? It is hard to see how it could do much to calm energy price inflation. But perhaps it will curb demand. That appeals to common sense. But is it actually born out by experience?

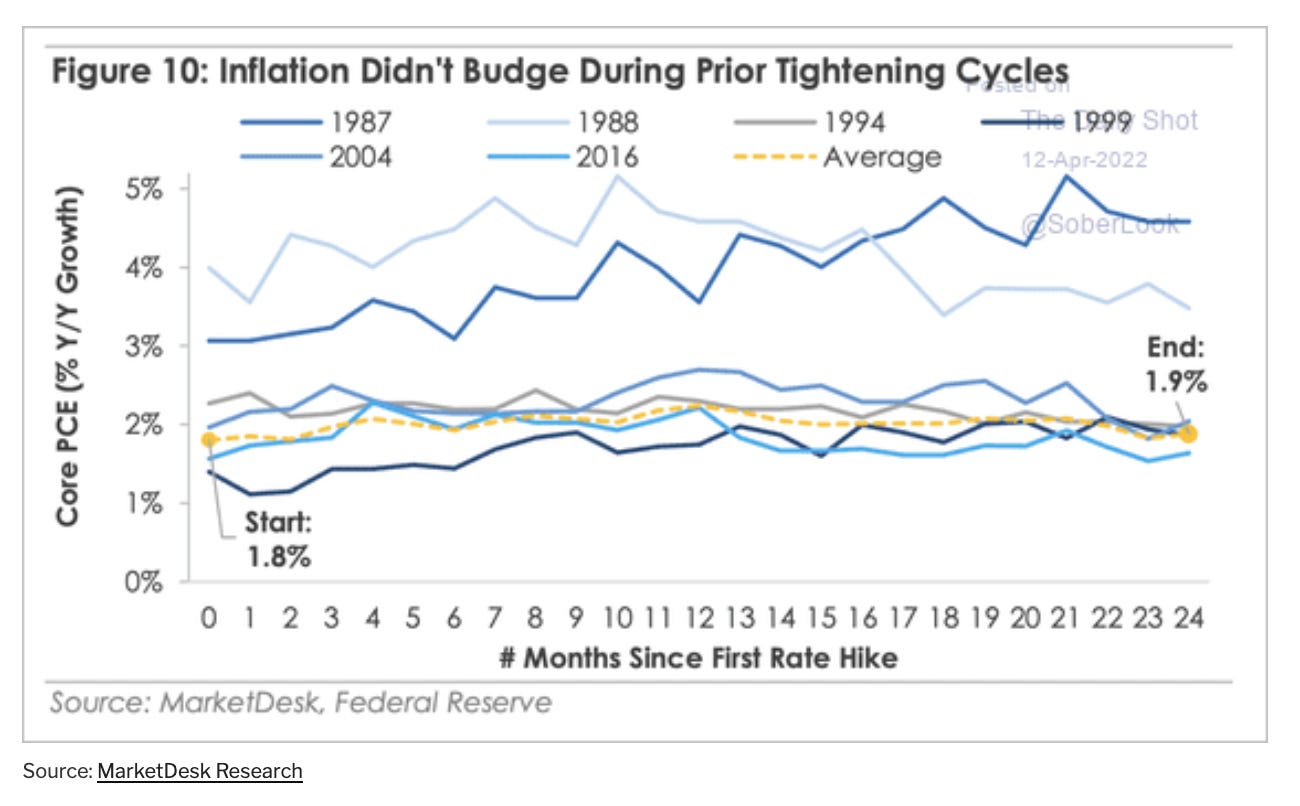

I’ll conclude with another amazing find from the Daily Shot.

With the naked eye it is pretty hard to detect any appreciable influence of Fed rate tightening on inflation in the US since the 1980s. Of course we all know about the Volcker shock. But that was extreme. In all the other tightening cycles since 1987 the effect has been virtually invisible.

Central banks WILL raise rates, since they are feeling immense pressure to "look like they are doing something." And since the only "something" they have is interest rates, they are going to raise them given the orthodoxy around monetary policy (never mind that inflation is a job for fiscal policy, NOT monetary policy -- that's a hornet's nest of an argument right there).

Of course, all this is likely to achieve is to tip us into a recession, since interest rates themselves can't magic away the underlying structural issues hidden beneath the top-line inflation numbers (which themselves mask 10s or even 100s of individual price sectors).

So, rates will be raised via the same logic that gave us "in order for the village to be saved, it was necessary that it be destroyed" ...

It might be time to reappraise monetary policy in it's entirety and accept that the basis of it was always a partial fallacy and that the real driver of inflation and the economy is trade policy, labor policy, fiscal policy and foreign policy. All monetary policy achieves is the creation of an ever larger pool of credit instruments through lower interest rates and implicit guarantees of creditors which excites economic activity in certain areas linked (in various ways but primarily financial) to the credit pool.

If you put interest rates above a certain point (I don't know what this is but I guess it's linked to the size of the credit pool relative to real economic activity) you reduce the credit pool by creating a credit crunch which would eliminate lots of debt but also lots of aligned economic activity and cause a recession due to the resulting loss of confidence. You might reduce inflation but you will also definitively damage the economy and the credit pool.

If you don't put rates above this point you reduce the credit pool via financial repression whereby the effective asset price increases erode the effective relative value of the credit pool. There is a slow deterioration in the size of the credit pool relative to the economy but it is gradual and happens over time.

I would bet that the Fed will opt for the second option. It might upset savers but a gradual deterioration in a certain group of people's relative net worth is less painful than a sudden deterioration in everyone's net worth.

Interestingly, neither of these outcomes will really matter for the people who are experiencing actual changes in their incomes and their living costs. These will be far more influenced by trade, labor, fiscal and foreign policy at a governmental level but given modern politicians don't really propose anything of any substance to change any of these policies then it's unlikely that things will change dramatically and that the macro-trends of increasing financialization, concentration of wealth, precarity for an increasing proportion of the population, decline in public services and distraction of populations with populist culture-war topics (scapegoating minorities, false-flag victimhood) while collective living standards decline will continue. Oh, and climate change will mean the world becomes less habitable.