In trying to wrap my head around the Mariupol siege and the battles for the cities of Ukraine that seems to be looming, I have been going back to two bodies of writing that were very much to the fore in the 1990s and 2000s:

(1) the military-technical literature on Military Operations on Urban Terrain (MOUNT).

(2) and the literature on “urbicide” - war waged not just on urban terrain but against cities as such - work which came out of critical urban sociology.

Strands of both literatures were important in helping to shape the study of what one might loosely call “new wars” from the 1990s onwards.

Tellingly, the notion of urbicide coined by anarchist science-fiction author Michael Moorcock in 1963 was first taken up by critics of urban redevelopment in the United States, to characterize the bulldozing and reconstruction of American cities around the needs of the car.

These interventions were not only destructive of urban space, but went hand with the clearance of Black neighborhoods and new forms of segregation. In light of the shock, it hardly seemed exaggerated to refer to a war on urban space.

In the early 1990s, the concept of urbicide was revived with a more literal intensity to make sense of the appalling destruction of the towns and cities of Bosnia in the Yugoslav wars. In particular, it was mobilized in 1992 by Bosnian intellectuals and architects to conceptualize the destruction of the historic city of Mostar.

Some of the testimony and documentaries of the period are truly shocking in their uncensored form. This report by Jeremy Bowen, on life and death in Mostar -"UNFINISHED BUSINESS" – BBC 1993. (The War In Mostar) - is unforgettable.

The return of siege warfare forced a reflection on the longer history of this kind of warfare.

As Mary Kaldor noted in her essential work on “New Wars”, one way to read the Yugoslav conflict was as a collapse back into archaic ethnic strife. But, as the decade wore on that became increasingly implausible. Instead, what it seemed that we were witnessing was a new configuration of war, or the mode of war-making.

To simplify a huge debate brutally, “new wars” were more informal, unconventional, asymmetric and they were conflicts taking place in a world that was increasingly urbanized. Ever more often cities became battlefields.

As Michael Desch put it rather brutally:

Asked why he continually robbed banks, Willy Sutton said, “That’s where the money is.” One could answer the question of “why fight in cities?” with the equivalent answer: “That’s where the people are!”

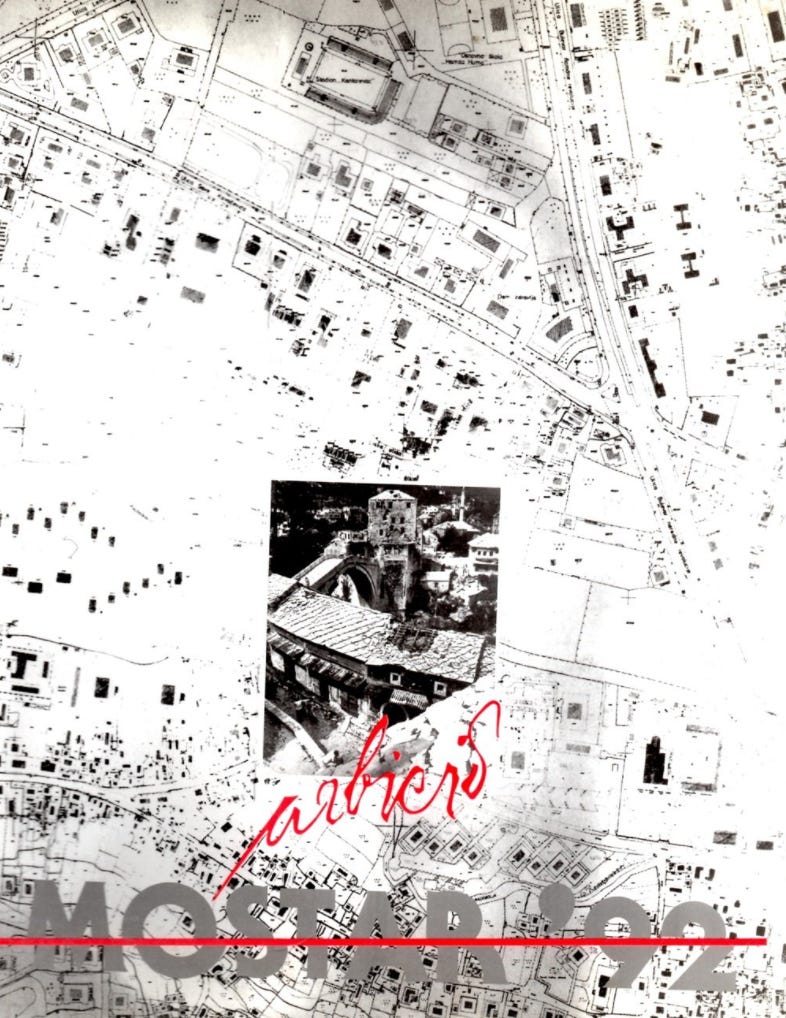

To see the force of that point consider that in 1900 only one in ten of the world’s population of 1.8 billion lived in cities. That is a 180 million people living in cities all told. Only rich countries in Europe and North America had high rates of urbanization. Today, the world’s urban population is over 4 billion. In the first decade of the 21st-century for the first time in the history of our species, the number of city-dwellers overtook the rural population. So yes, if we fight wars today, it is more likely that we will fight them in cities.

Source: Our World In Data

Of course, the “urban revolution” of the late 20th century cannot account for the fact of fighting in city like Baghdad, which was founded in the 700s, or a medieval town like Mostar.

But if we look past the question of historic origins of particular cities, and look instead at the form of the urban space in which combat took place, we can see something distinctive and modern in this new kind of urban warfare from the middle of the twentieth century onwards.

Strategic bombing, for instance, targeted the city as a site of production, social life and politics. Not only did you have to have the technology to do it. But, as the discovered in Vietnam, carpet bombing rice paddy has its limits as a strategy of war.

The genocidal racial visions of the Nazi regime was keyed to the development of urbanism in the negative sense that it envisioned rolling back the tide of urbanization in Poland and much of the occupied Soviet Union. Subhuman slavs would not live in cities and tens of millions of them would not live at all.

World War II also witnessed the battle itself taking place within the modern city. War was directly shaped by the urban spaces created by mid-century modern development. In Stalingrad, the giant factories and city gardens created by Soviet development in the 1930s became battlefields. They proved to be ideal terrain of defense. Fortresses waiting to happen.

As apartments and offices were raised into the air in the form of the high-rise and the skyscraper, so the battle went vertical as well. At the latest since Israel’s siege of Beirut in 1982, war amongst the high-rises has become a recurring image of modern cognitive dissonance.

The dissonance is unforgettably captured by Mahomoud Darwish’s description in Memory of Forgetfulness of making coffee in his modern apartment under bombardment by Israeli jets.

Planned, high-rise, industrial development created the great towering monuments of twentieth-century urbanism and created ideal locations for snipers, who hunted their prey from living room and kitchen windows 30 floors up.

But modern urbanism, for most people in most of the world does not consist of giant factories and high-rises. It has instead taken the form of the sprawling informal developments that surround every low and middle-income city around the world, from Lima to Fallujah.

Accordingly, much of the urban fighting of the late twentieth-century and early 21st-century has been “low-rise”, fought across roof tops and narrow alleys, festooned with pirated power lines.

So ominous is this sprawl of informal settlement from the point of view of conventional military doctrine, that one Israeli analysts referred to urban sprawl itself as a mortal threat to his country.

Uncontrolled spontaneous urbanization is a threat of war! The attacks against us are not physical but are aimed at our very order. The threat is not conventional or terrorist, but invasive. In the context of the global War on Terrorism, this is very important. It is destructive not through direct damage but through its invasive spread which will eventually kill off the host state. As of today we have a tumour installed within the Israeli system. This is a cancerous threat; the cells multiply. We see a mosque appearing there; a mass of buildings here. Thus we see order destroyed.footnote

This horrifying quote comes from retired Brigadier General Eitam, former commander of Iraeli forces in South Lebanon, quoted in an influential essay by Stephen Graham on “The Lessons of Urbicide” published in New Left Review of 2003.

In 2004 Graham edited a landmark collection of essays centered around the theme Cities, war, and terrorism: towards an urban geopolitics. This is essential reading in the current moment.

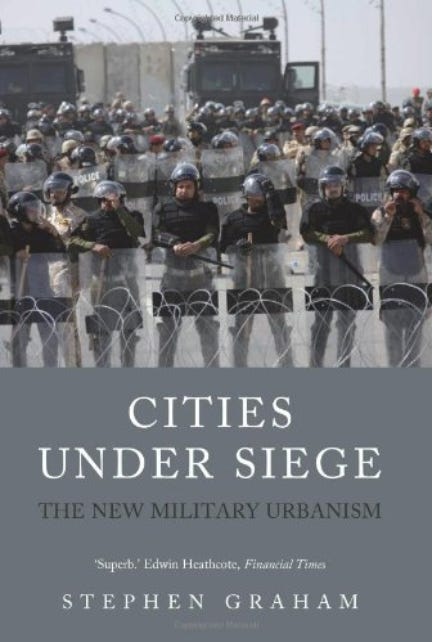

After the massive violence in Iraq and Gaza over the following decade, Graham’s magnum opus on the theme appeared in 2011.

As Graham explains:

War has entered the city again - the sphere of the everyday. •s In the 'new' wars of the post-Cold War era - wars which increasingly straddle the 'technology gaps' that separate advanced industrial nations from informal fighters - the world's burgeoning cities are the key sites. Indeed, urban areas have become the lightning conductors for our planet's political violence. Warfare, like everything else, is being urbanized. The great geopolitical contests - of cultural change, ethnic conflict and diasporic social mixing; of economic re-regulation and liberalization; of militarization, informatization and resource exploitation; of ecological change - are, to a growing extent, boiling down to violent conflicts in the key strategic sites of our age: contemporary cities. The world's geopolitical struggles increasingly articulate around violent conflicts over urban strategic sites, and in many societies the violence surrounding such civil and civic warfare strongly shapes quotidian urban life. In the process, the distinctions between wars within nations and wars between nations radically blur, making long-standing military/civilian binaries increasingly unhelpful.66 Indeed, what this book labels the new military urbanism tends to 'presume a world where civilians do not exist:67 All human subjects are thus increasingly rendered as real or potential fighters, terrorists or insurgents, legitimate targets

Fighting in cities had specific effects on the societies caught up in war. The spaces involved might be small, but they were highly significant. A lot of social life is compressed into a city.

As Martin Coward’s Urbicide The politics of urban destruction explained, urbicide had the effect of annihilating the physical space in which communities mixed. Urbicide and genocide were close cousins.

In the mixed communities of Bosnia this was particularly dramatic. As Coward writes about the destruction of the Stari Most bridge in Mostar

These images of the assault on a bridge literally linking east and west gave graphic representation to the notion that the former Yugoslavia was being forcibly ‘unmade’.

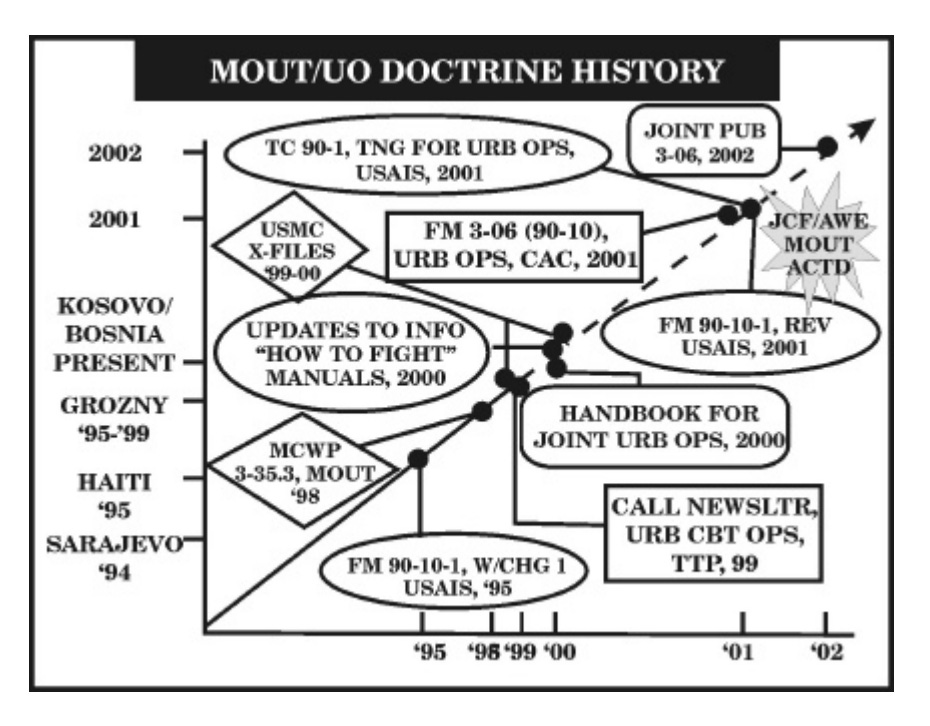

In the 1990s and 2000s, the urbicide literature in the critical social sciences ran in parallel with an intense discussion within the military ranks, the ranks of military advisors, security experts and historians about a new buzzword, Military Operations in Urban Terrain, aka MOUT.

On the basis of their experience in Somalia the US military were scrambling to devise a new urban warfare doctrine.

Source: Soldiers in Cities

For a modern army, centered on fast-moving mobile operations, with ground troops that are not simply tank-centric, but mechanized and motorized in a comprehensive sense, the urban space is challenging. The city may have been remodeled for the motor car. It is no longer ringed by city walls as was true across Europe until the late 18th century. In the early 19th century those walls were commonly razed to enable more traffic. Check out this fascinating history by Yair Mintzker on the defortification of Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries.

But even without fortress walls, the urban space can, all too easily, be made very hostile to an attacking force. For starters, tank guns are generally neither capable of elevating or depressing sufficiently to engage enemies at close quarters in cities. For infantry the urban space is truly terrifying.

It is true, famously, that wider avenues make the construction of classical barricades more difficult (Haussmann etc). But those wide roads also open fields of fire, they are terrifying to cross for attacking infantry. They make excellent killing zones for troops bunkered on either side, or perched at high vantage points to deliver plunging fire.

One early set of lessons of urban combat in the 20th century were collected in the volume edited by Michael Desch, Soldiers in cities. Military operations on urban terrain (2001)

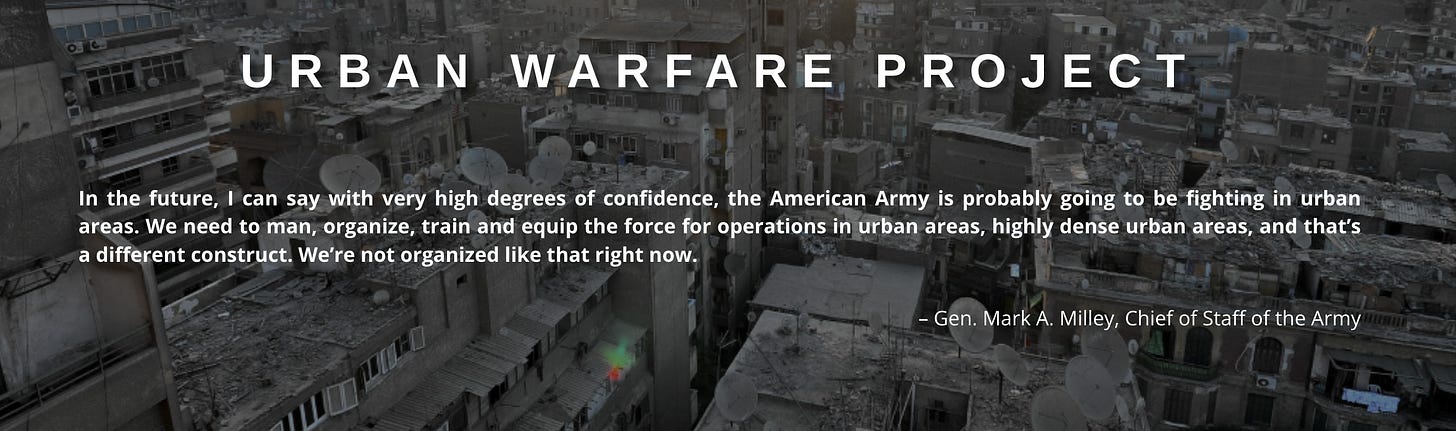

If you want to see the state of the art twenty years on, check out West Point’s Modern War Institute, Urban Warfare Project It comes with a ringing endorsement from General Milley, which could be taken directly from the critical urban studies literature of the 1990s or 2000s.

For good reason, Russia’s two campaigns against the city of Grozny in Chechyna feature in both the literature of urbicide and MOUT. The two campaigns were both an example of massive urban destruction and an example of military lesson-learning between the disastrously botched attack of 1994-5 and the brutal success of 1999-2000.

For a graphic impression of how badly things went wrong in 1994 check out this extraordinary video documenting the destruction of Russia’s 131st Maikop Brigade in Grozny.

Since 1999-2000, unlike the US or Israeli armies, Russia has not been fully committed to full-scale urban warfare.

Perhaps not surprisingly after its experience in Grozny, in 2008 Russia stopped short of a final assault on Tbilisi. The Georgian capital was bombed but never assaulted in earnest.

In 2014, following the occupation of Crimea, there were fights for control of cities cross the Donbas region. But these were relatively small clashes. In March 2014 Putin decided against full-scale invasion in Ukraine. The fighting in the Donbas that followed did not involve major sieges of cities and Russia not did it publicly commit its main force.

On the character of the fighting in the Donbas, I highly recommend Brothers in Arms. Military Aspects of the Crisis in Ukraine edited by Colby Howard and Ruslan Pukhov, published by the CAST think tank in Moscow.

The essay by Mikhail Barabanov on “Viewing the action in Ukraine from the Kremlin’s Windows”, should have been essential reading this winter. He outlines with dramatic clarity the impasse of Putin’s strategy in Ukraine.

In 2015 Russia became involved in the devastating city-fighting in Syria, but mainly through airpower. Russia says that 63,000 service men rotated through the Syrian arena. But a small fraction of those will have been close to urban combat. To judge by the unit affiliation of the casualties acknowledged by Moscow, those close to the action were overwhelmingly air force and special forces as well as a smattering of artillery troops.

This reconfirms the basic point. Unlike the US or Israeli or for that matter the Turkish militaries, the Russian army has relatively little recent experience of high-intensity large-scale urban warfare.

And urban warfare in Ukraine is large-scale.

Mariupol before the war had a population in the 400,000s, bigger than Florence, almost as large as Dublin, comparable to Stalingrad’s population of 490,000 in 1940. The fighting in Stalingrad in 1942-1943 swallowed up entire armies. In Mariupol today neither side has the troops either to fully defend or comprehensively assault the city. The main force in the Ukrainian defense is reportedly a single brigade, the 36th Naval Infantry.

This video shows the Ukraine unit training with US Marines in 2021.

Mariupol is a lot for Russia to swallow.

Kyiv is a challenge of an even greater scale. With 2.9 million inhabitants in peacetime, it is the 7th most populous city in Europe, larger than Rome or central Paris. Kyiv’s population is almost six times larger than that of Stalingrad in 1940. With well-supplied and determined defense, Russia’s entire invasion force on all fronts (c. 190,000 men) could be swallowed up in fighting for just one part of modern day Kyiv.

As one timely post on Linkedin pointed out, Russia’s military experts were preparing sophisticated new schemes for urban warfare in recent years. These involved the use of precision artillery fires to seal off parts of a city.

But little of that has been in evidence so far. Instead, we have seen an ill-directed and bludgeoning assaults lacking clear operational rationale. The suffering of the Ukrainian civilian population has been horrible. But Russia has not yet demonstrated that it has the capacity to mount an urban assault intense enough to deliver the symbolic victory that Putin needs.

"Tellingly, the notion of urbicide coined by anarchist science-fiction author Michael Moorcock in 1963 was first taken up by critics of urban redevelopment in the United States, to characterize the bulldozing and reconstruction of American cities around the needs of the car."

Ha. The master work on this very matter is Robert Caro's magnificent, "The Power Broker" detailing Robert Moses destruction of great swathes of New York. Unforgettable read. Meanwhile, we all wait and pray that Mr. Caro, now well into his 80s, completes his fifth and final volume of his even better bio of LBJ. If you want to understand American politics in the raw, start there. Thousands of pages in toto. Unputdownable.

Intense, informative, gut-wrenching. Thank you as always for the nitty gritty facts and timely situational history, AT. Now I have to go have a whisky, or three. Whew.