Chartbook 240 - Carbon notes #6: America's auto strike and a century of transition in the US car industry.

A strike in the heart of American car industry is always big news. The auto industry is at the heart of US economic history. Historically, strikes in the sector have reshaped America’s social contract. Those echoes dimly reverberate about the current dispute. Having decided to support the UAW picket, President Biden doubled-down by signaling the historic significance of the struggle. As Eric Levitz reported.

Wall Street didn’t build this country, the middle class built this country. The unions built the middle class. That’s a fact. Let’s keep going, you deserve what you’ve earned. And you’ve earned a hell of a lot more than you’re getting paid now.” Asked by a reporter whether he was specifically endorsing the UAW’s demand for a 40 percent pay increase over the life of the next contract, a chorus of chanting workers pressured Biden into saying “yes.”

Donald Trump on the other hand, who is also wooing the American working-class, met with non-union workers. Both candidates clearly feel that the strike is an unmissable political event.

To locate in America’s current economic history we need more context.

On the Ones and Tooze Podcast, Cameron Abadi and I talked about the strike and the significance of Biden’s appearance.

As important as the strike undeniably is, what hangs over it is the question of how we ended up here. Even within the US automotive industry, the Big Three centered on Detroit are now just part of the national jigsaw puzzle, which also includes major production and distribution networks of European and Asian producers, plus Tesla, America’s world-bestriding, non-union EV pioneer. And the United States, once the undisputed hub of the global car industry it itself just one part of a complex global scene, dominated by non-American players.

***

For much of the 20th century, at least through to the 1980s, the auto industry more than any other defined the distinctiveness of the American economy and what made it so rich.

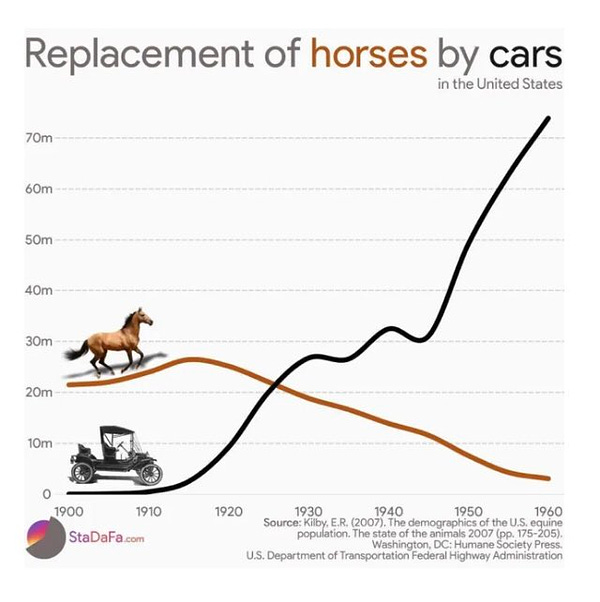

The transition from a mobility system based on railway and horses, to one largely based on cars and trucks redefined the American way of life quite suddenly in the early 20th century.

Henry Ford’s model of mass production, first pioneered with the Model T introduced in 1908. was credited with a gigantic and unprecedented surge in productivity. Ford’s River Rouge plant became a site of pilgrimage for industrial engineers from all over the world. In 1914, Ford’s introduction of the $5-day, made possible by the exhausting productivity of his mass assembly lines, transformed the wage-price bargain. By the mid 20th century Fordism had come to stand for a particularly American style of mass production, which would enable workers themselves to consume the fruits of their labour.

Stefan Link’s recent book offers a fascinating political and economic history of the global phenomenon.

Source: Princeton UP

It is hard to exaggerate how closely the rise of US power In the 20th century was associated with the car. In the aftermath of World War II, a staggering 80 percent of all cars manufactured around the world were made in America. By the 1960s Detroit was the city with the highest per capita income in the United States.

Fordism was a productive force with geopolitical consequences. Detroit was pivotal to America’s emergence as the arsenal of democracy. If you could mass-produce cars, you could mass-produce bombers, that at least was Ford’s idée fixe.

It was a productivist vision that echoed down more than half a century to the present day, where both advocates of the Green New Deal and Donald Trump’s Operation Warp Speed cite mass production of aircraft in World War II as evidence for what American industry is capable of doing under the right kind of direction.

Today, figures from tech and finance are the pinups of capitalism. In the mid-century moment, car executives were at the cutting edge. In the 1950s and 1960s the Secretaries of Defense for Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson were auto executives - Charles Wilson of GM and Robert McNamara of Ford.

Fordism was not simply a system of mass production. It was also a social model. Insofar as America had a post-World War II welfare bargain, it was defined by the struggles between the auto firms and organized labour between the sitdown strike of 1936-1937 and the Treaty of Detroit struck in 1950 between General Motors and the United Autoworkers. This effectively set America on course for a model of welfarism based on private provision of health care and pensions, unemployment benefits and cost of living based wage adjustment. This agreement between the UAW and the auto industry founds the ongoing conflation in the United States between the “middle class” and the “working class”. Still today the workers represented by UAW are bargaining for their entire package of compensation, not simply wages.

For those who were part of the core automotive workforce this delivered much higher than average wages and corporate benefits.

Source: EPI

As the data show, autoworkers remain amongst the best paid manual workers in the United States, but the remarkable ups and downs of the real compensation curve since the 1970s succinctly summarize the increasingly precarious and embattled nature of their privileges.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s though American autoworkers never had it so good, the industry was in fact growing mainly elsewhere in the world. In 1950, the US accounted for roughly 75 percent of global production of cars. But, thereafter, in terms of units, output in the US remained remarkably static, at about 10 million vehicles per annum. Output expanded in the Americas, but in Canada and Mexico, driven by investment from Detroit and Europe. The great acceleration took place not in North America, but in the further reachers of the American sphere of influence - in Japan and Western Europe.

In the 1970s against the bakdrop of the oil price shocks of 1973 and 1979 this competition spilled back on the United States with a dramatic erosion of the market share of the Detroit Big Three.

In the 1970s, in defense the UAW mounting a series of aggressive strike actions and at least at first it was still able to force the Big Three to honor labour contracts concluded in Detroit in their factories around the country. But by the 1980s not only were imports flooding in, but Detroit’s European and Asian competitors were beginning to establish production facilities in the US, above all in Southern states hostile to trade unions.

Between 1979 and early 1980s the first of the dominoes to fall was Chrysler, which went bust. Meanwhile Ford and GM struggled to maintain their market share. Carter bailed out Chrysler. The Reagan administration bullied the Japanese to limit imports. But Detroit entered an irreversible trajectory of decline. Since 1980s it is no longer the US firms, but above all Toyota that has led the global industry.

The global employment figures at GM tell a tale of the rise and decline of the industry. GM’s US employment peaked in 1979 at 618,365, making it the largest private employer in the United States. Worldwide employment was 853,000. Since then it has been one way decline. In 2022 GM employed 167,000.

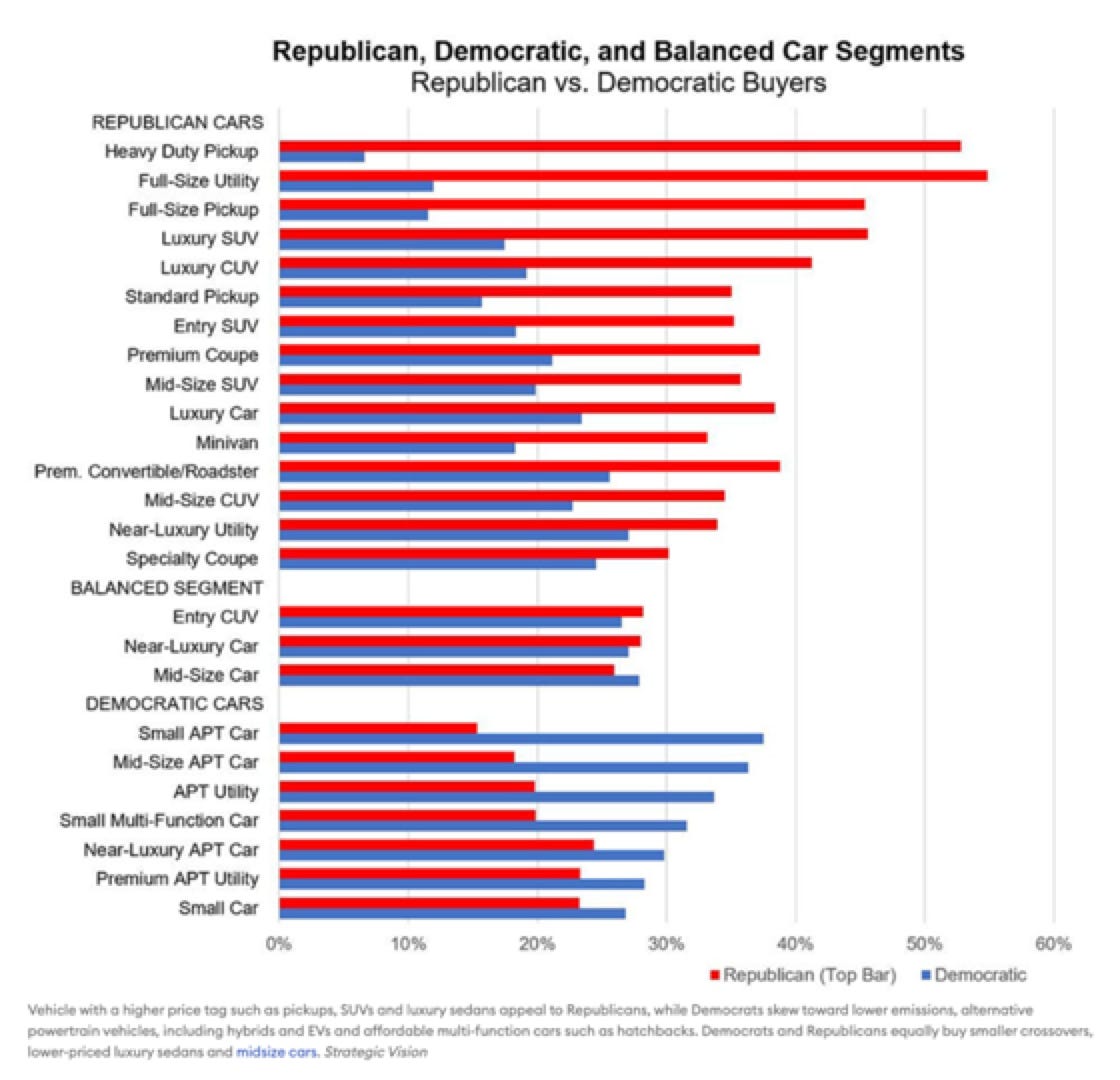

The American industry did not take defeat lying down. In the 1980s the American industry casting around salvation invented the SUV. Ford meanwhile, has done relatively better than GM and Chrysler because of the enduring popularity of the truck, and specifically the F150 franchise. Whilst suburban American families shifted to SUVs, red-blooded patriotic GOP-aligned Americans are the prime consumers of pickups.

Bush and Clinton’s effort to pass NAFTA opened the door to decentralizing supply-chains to Mexico. Increasingly, the North American industry reconfigured itself as a hub in a global industry organized around regional clusters. The auto industry may have been increasingly unfashionable in the early 21st century but it was in fact one of the main business drivers of globalization.

Not only did the Big Three regionalize production across North America. GM in particular followed its Asia and European counterparts into China. In 2021 GM sold more cars in China than in the US. Indeed, it sold more cars in China than in all other geographies put together. VW is not the only major global car company facing a “China question”.

Source: Stockdividend

America’s home market meanwhile increasingly became an arena for the enactment of the culture wars that divided American society. The bestselling vehicle of all time is the F-150, an icon of MAGA. Market research shows that ownership of expensive, gas-guzzling pickups skews Republican v. Democrat by a ratio of almost 8 to 1.

At the same time however America has also been a launching pad and test bed for E-mobility. It was in California from the 1970s that the first experiments were conducting with battery driven cars. In the 2000s it was liberal Americans who were the early adopters of the first truly successful hybrid vehicle, the Toyota Prius. In the age of the Bush Presidency, oil wars and republican climate denial, driving a Prius was a badge of honor for progressive Americans.

Americans not only like their cars. They need them. But given the huge presence of foreign makers, that by itself no longer secures the future of the Detroit Big Three which have not only to make cars but make a profit doing so. Whereas Ford’s niche strategy meant that it withdrew step by step from making ordinary cars, GM and Chrysler found themselves deeper and deeper in trouble. In 2009, following the 2008 crisis, the unthinkable happened. Not only Chrysler, but GM declared bankrupt. And the telling thing was that unlike in the case of the banks, it took the Obama administration several weeks to decide whether to save them. The conditions ultimately imposed were far more onerous than those required of the banks on Wall Street. The workforce took a significant hit to wages.

It was more than merely a corporate disaster it affected American society as a whole and its self-image. In the 2010s a commonly quote set of numbers compared GM and Apple in their prime: In 1955 GM earned revenues of 105 billion in 2010 dollar terms well-nigh identical to Apple’s earnings in 2014. In 1955 GM generated this revenue with an American GM workforce of 470,000 as well as 70,000 staff working overseas in subsidiaries such as Vauxhall, Opel or Holden. It would go on to assemble a peak workforce of over 800,000 in the 1970s. In 2012 Apple, the iconic American firm of the decade, generated $ 108 billion in revenue, with a US staff numbering only 40,000. Overseas only 20,000 were employed directly by Apple. The vast majority of its workforce consisted of 700,000 foreign contract staff. GM was an American company with a clearly identifiable global footprint. Apple, by contrast, is a complex global network with a Californian brain.

In the summer of 2013, Detroit, the once proud home of what had once been America’s greatest industry, declared bankruptcy. In the aftermath the image makers of America’s surviving car industry doubled down on its hard-knocks story. This remarkable pastiche of Americana delivered by none other than Bob Dylan, during the 2014 Super Bowl is redolent of the mood.

One way of thinking about the populist phenomenon in the United states since the 2010s, is in terms of the crisis of Fordism. Cars are what American politicians gesture to when they want to demonstrate economic nationalism.

***

In the ten years since, the US legacy car firms have recovered, have substantially upgraded their offerings and have earned handsome profits. But the classic era of the Detroit, internal combustion engine industry is clearly nearing its end.

Though Toyota led the first steps towards hybrids in the 2000s, in the 2010s it would be an American firm that made the step to full, battery-powered E-mobility. But it would not be any of the Detroit big three. It was be Tesla. From nowhere, riding on a wave of enthusiasm about its remarkable demonstration of the viability of e-mobility, in 2017 Tesla’s market capitalization overtook that of Ford and GM.

In October 2021, America’s newest auto champion, a non-union firm would be valued at more than the next top 10 automakers put together.

***

As Tesla knows only too well, it is competing not with Ford, GM and Chrysler, but with the high end European brands and with new competitors in its key market in China.

Despite the President’s rhetoric, the battle going on between the UAW and the Big Three will not decide the future of the American middle class, or even the future of the auto-industry in the United States, let alone the rest of the world. But it is nevertheless a key part of the jigsaw puzzle of the energy transition. In the EV transition, the Big Three are racing to catch up with their advanced competitors. Their investment plans foresee pouring $100 billion into new production facilities. Acccording to estimates by VW and Ford, these plants will on balance required 30 percent less labour to build an EV. This is the shadow hanging over the 150,000 auto workers represented by the UAW. There will be no new Treaty of Detroit. The new battery plants and EV factories, whether built by the Big Three or foreign manufacturers are spread North-South along the auto corridor from Michigan to Mexico.

But as Eric Levitz points out apart from the pay and conditions of the workers involved in the dispute, the strike has crucial political significance, because it reveals the stark difference between the two parties contending in the elections next year:

One party is capable of rallying to labor’s side, when presented with sufficient intra-coalitional pressure and electoral incentive. The other party will project a populist image while channeling workers’ grievances toward targets other than their employers and partnering with low-road businesses to erode labor’s bargaining power. Whatever else comes out of the UAW’s strike, it has at least made the choice facing American workers clear.

This is the message that the Biden team have been pushing not just since last week but since the start of the Presidency. And they have policy to show for it. The fact that the polling is nevertheless as close as it is, with many polls showing a substantial lead for Trump in a head to head with Biden, tells you how dangerously poised the situation in the United States will be in 2024.