Adam Tooze's Chartbook #28: China in 1983, a miracle waiting to happen?

The World Bank's first report on Socialist Economic Development

Chartbook #28 accompanies the cover story I did for the latest issue of the New Statesman on China’s twentieth century history. The New Statesman piece is a bit of a high-wire act suspended btw J.A Hobson and Larry Summers. Check it out here.

One of the most intriguing things I read whilst researching the piece, was the World Bank’s report on China’s Socialist Economic Development from 1983. What is so fascinating is that this was the first time that the World Bank had the chance to do an in-depth analysis of China’s development under Communism. The report asks all the questions one might be tempted to ask at that point. Where was China at after the end of Maoism? What distinguished it from other low-income Asian giants like India or Pakistan or Indonesia. Was China about to take off?

Before we get into that, a brief note on Chartbook and how you can contribute to its future.

**********

Chartbook started as a free newsletter and I want very much to keep it that way. If you need to read Chartbook Newsletter for free, you are welcome to do so. If you can’t afford a paid subscription, or if you read it in a context where paying subscriptions is inappropriate, I get it. You don’t have to do anything. You will continue to receive the newsletter as before.

But, writing the newsletter takes a lot of time and effort. I have to juggle it with all sorts of other commitments. So, if you can afford to, if you think the Chartbook content is valuable, if you would like to support the mission, or, simply, to buy me the equivalent of a cup of coffee once a month, please click here:

There are three options:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club: $ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

What do you get in return? First and foremost, good karma. In addition, for paying subscribers I have started a series of regular emails featuring the most interesting, engaging or simply weird links I have come across over the previous few days. Check out Top Links #1 and #2. More to come.

With the release of Shutdown on September 7, there are more goodies on the way. The highlight will be Shutdown reading group sessions for paying subscribers. Details tba. To be on the invite list, sign up for one of the subscription options here:

Now, down to business.

********

In 1980 China joined, or in Beijing’s words, “resumed its lawful seats” at the IMF and the World Bank, aka “the Bretton Woods institutions”.

Source: BOC

It is too easily forgotten but as a major contributor to the World War II alliance, China’s nationalist government was very much part of the postwar financial negotiations that took place in the summer of 1944 at the Bretton Woods hotel in New Hampshire. The Nationalist regime was represented at the conference by a large and expert delegation headed by Hsiang-Hsi “H.H.” “Daddy” K’ung (1881-1967) governor of the central bank between 1933 and 1945.

When contacts resumed in the late 1970s the going was surprisingly easy. The politics of the encounter were fascinating. To read more about that check out Julian Gewirtz’s Unlikely Partners, a fascinating history of Western economics in reform-era China. I want to focus here on the report itself and the picture it gives us of China’s situation before the growth explosion.

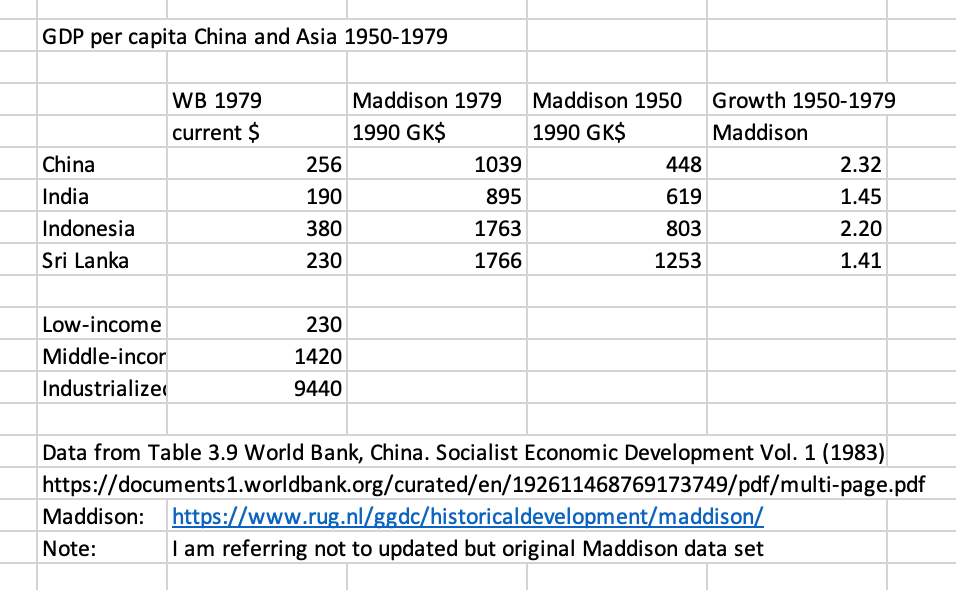

To start the story what was needed was a benchmark. What state was China in, when the Communists took over? The data used by the World Bank were produced by Michigan scholar Alexander Eckstein. The answer was stark. In the early 1950s, Communist China and India at independence were in a broadly similar place. Both were barely above subsistence. India’s per capita GDP was slightly ahead, as was its level of industrialization.

The authoritative estimates of PPP GDP per capita compiled by Angus Maddison decades later agree with Eckstein’s as far as India and China are concerned.

If the starting point in the early 1950s, was one of poverty and underdevelopment. Three decades later, what kind of society had the Communist regime made?

The World Bank did not hide the fact that there had been disasters. The terrible impact of the Great Leap Forward screamed out of the demographic data. Huge swings in mortality and fertility were visible in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In a society of China’s scale, such fluctuations can only be the result of epic catastrophe.

Visible too was the impact of the cultural revolution. In 1964 685,000 young people were enrolled at Universities in China. In 1968 that plunged to 259,000 and in 1970 to 48,000. As the World Bank noted in a fascinating annexe on the history of China’s statistical infrastructure, in 1968 China’s statistical offices were shut down. The office reopened in 1971 but ten years later it was still chronically understaffed.

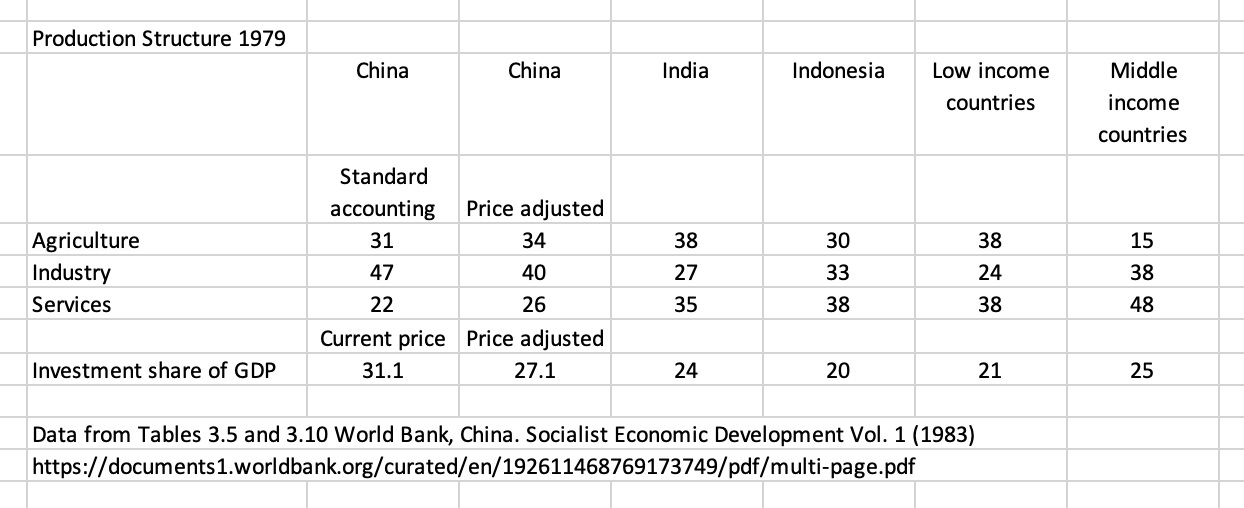

What was clear from the basic GDP data were two things. First, China in 1979 was still a very poor society ($1039 1990s dollars per capita per annum according to Maddison). Second, it had pulled ahead of India.

Strikingly, though income had doubled relative to 1950 and though population had practically doubled too, China had not urbanized. In 1949 the city and town population had accounted for 10.6% of the population. The urban share peaked at 15.4% in 1957. After that the share declined to 12 and 13 percent in the 1970s. That compared to more than 20 percent in India. The low urban share was all the more striking because in terms of the weight of its economy, China was considerably more industrialized than its low income peers.

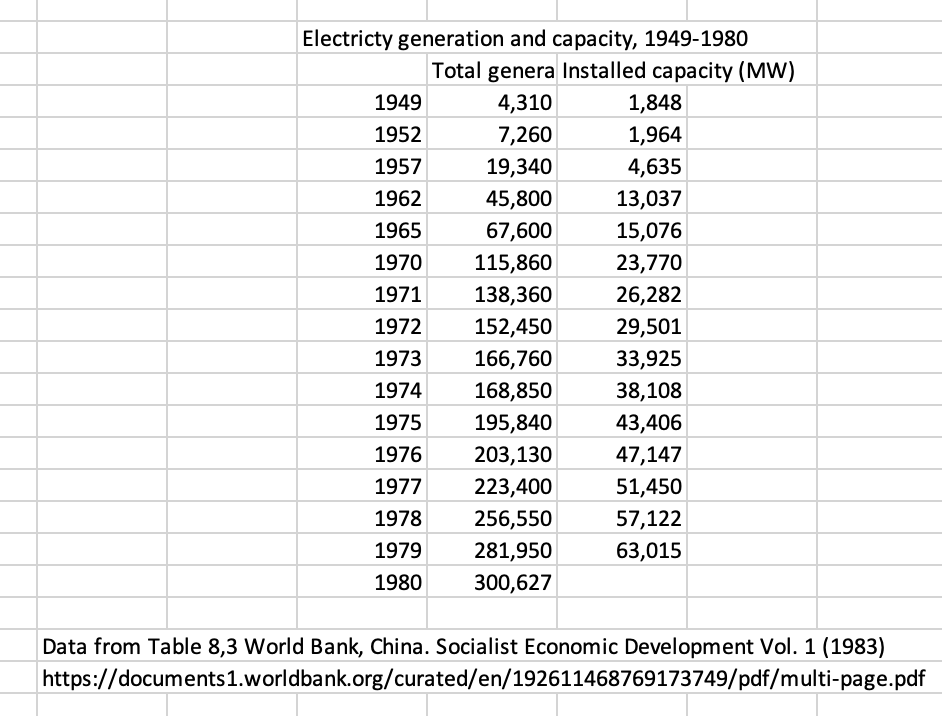

China had industrialized without urbanizing. This is confirmed by other material indicators such as China’s electricity consumption, which surged.

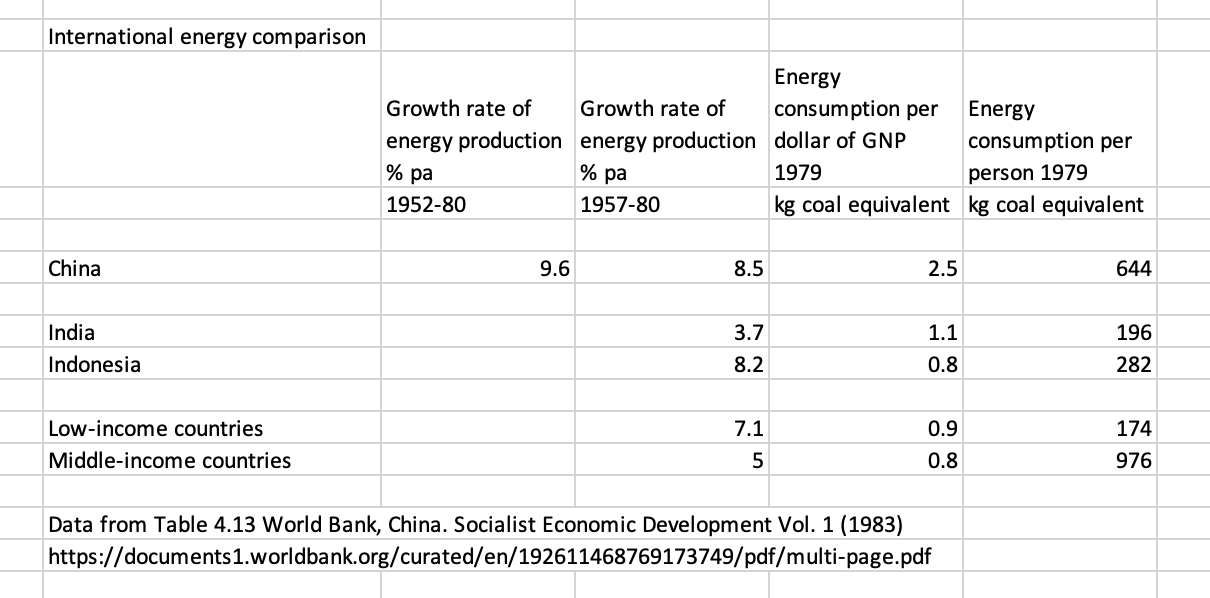

In terms of per capita energy consumption, by the 1970s China was already well ahead of other low-income countries. In 1979, per capita its energy consumption in China was three times that India. China had a huge coal industry. It was also, it is all too easily forgotten, a major producer and exporter of oil. More on this in another post.

Industrializing without urbanizing was remarkable, but it was not the unevenness of China’s development that most impressed the World Bank investigators. What struck them was that the Communist regime had laid the foundations for growth by delivering basic services to its population.

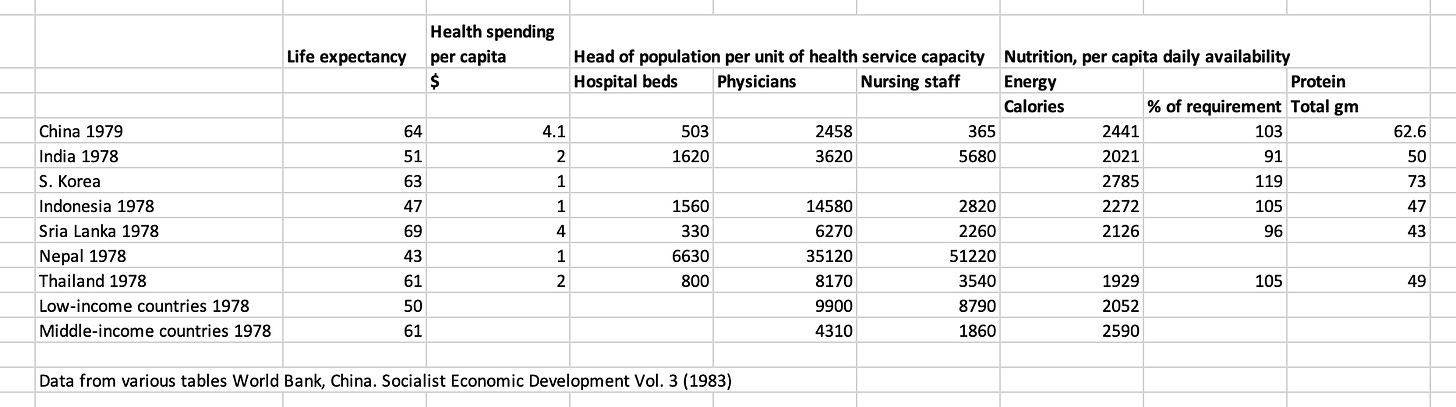

"China's most remarkable achievement during the past three decades", the Bank remarked, was to have made "low-income groups far better off in terms of basic needs than their counterparts in most other poor countries". As a result, the most basic indicator of human well-being, life expectancy had surged in China from 36 in 1950 to 64 in 1979. In 1979 China, the most populous country on the planet and one of the poorest, had an average life expectancy that put in the higher tier of middle-income countries. In Shanghai China’s richest province, average life expectancy in the late 1970s was 72 years, no more than a year behind that in the UK at the time. Overall life expectancy, at 64 years was in the words of the World Bank "outstandingly high for a country at China's per capita income level".

NB: The figure for China was chosen as 1957, presumably because the demographic data for 1960 were under the shadow of the Great Leap Forward.

Life expectancy reflects an entire complex of factors, but the World Bank did not hesitate in its interpretation. In its view it was due to the fact that unlike other low-income countries - notably India since independence - the Communist regime in China had secured a basic provision of food, health care and education for practically everyone.

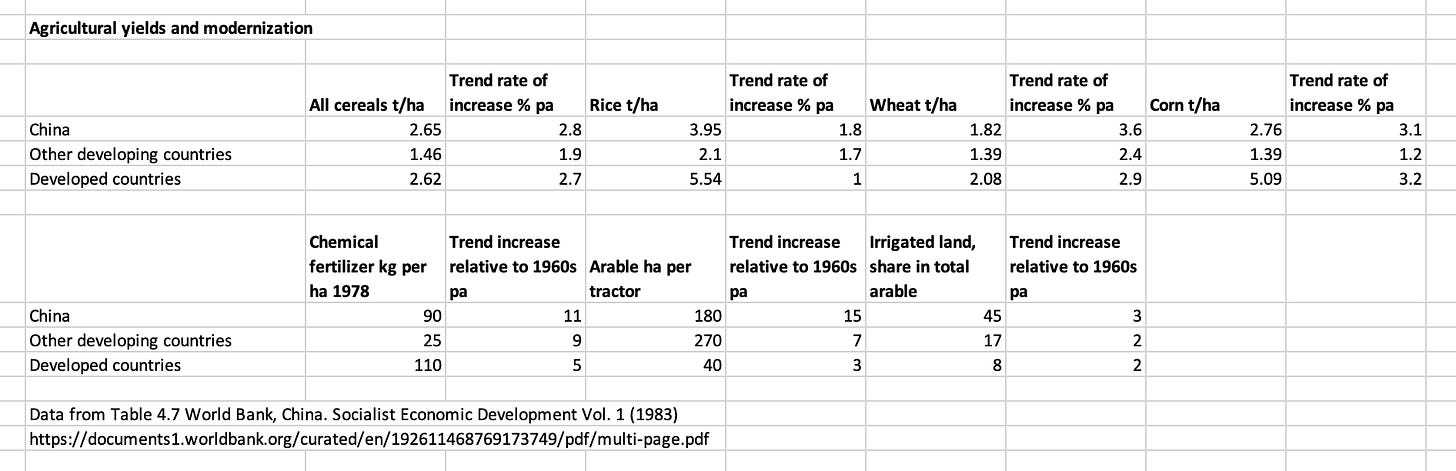

China’s superior nutritional level reflected the more advanced state of its agriculture. Reduced to a common denominator of grain-equivalents the World Bank estimated that China’s agricultural production per capita was 27 percent higher than that of India in 1979. The endowment of Chinese agriculture with farm machinery and the use of fertilizer was far greater than in India. Yields per hectare were higher, as was historically the case.

The World Bank’s statistics painted the picture of a Chinese agricultural economy that used a high intensity of industrial inputs to produce superior yields per hectare compared to most low-income countries. It was clearly not optimal - the entire complex history of agriculture under Communism said otherwise - but, it was enough to ensure adequate food availability.

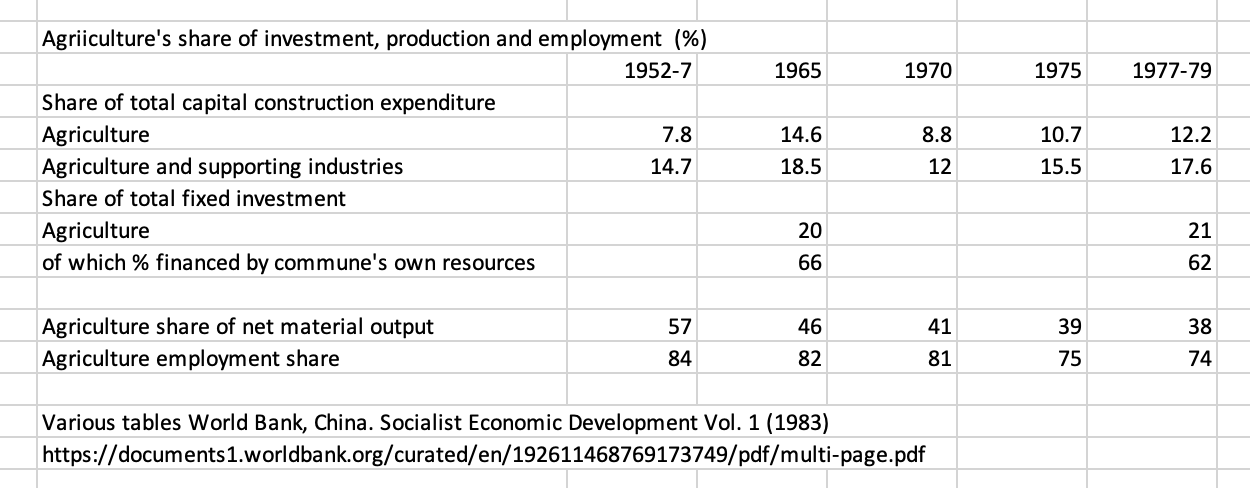

Though Chinese farms were equipped with more modern equipment than their Indian counterparts, that did not reflect any special priority accorded to agricultural investment. On the contrary, given agriculture’s share of production and employment, it was drastically starved of new investment.

It was not high spending on rural development, that secured the far better outcomes for the mass of China’s population but the comprehensive organization of social services and the priority given to food distribution, education and health .

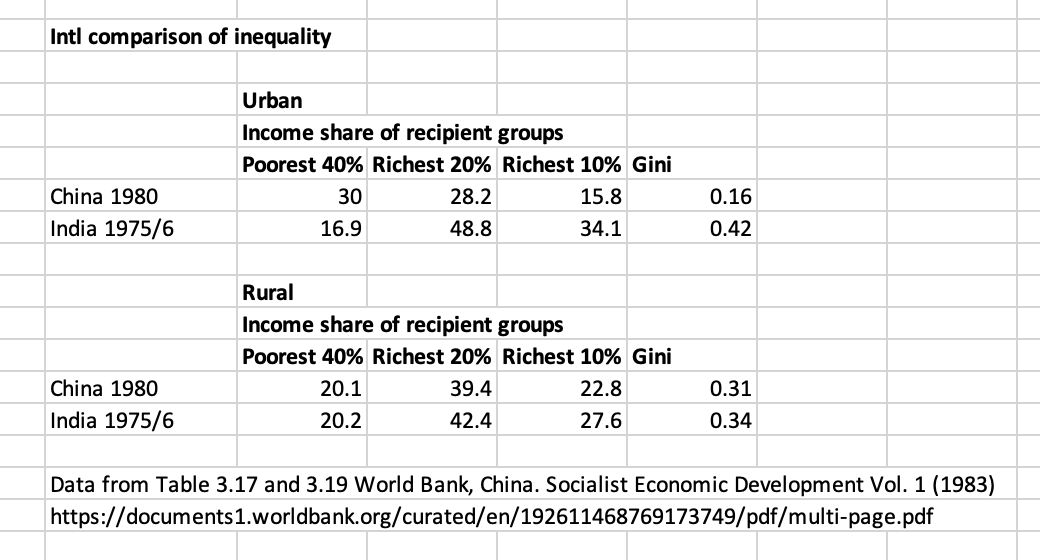

Mao’s Marxism was distinctive in its focus on the peasantry. But viewed in terms of income distribution it was in the city rather than the countryside that the redistributive quality of China’s regime was most evident. Whereas the cities of other poor countries were places of extreme inequality, China’s cities in the Mao and immediate post-Mao era were places of relative equality. In China, the gini measure of inequality was lower in the city than in the countryside, in India the reverse was true.

Meanwhile, China’s fiercely invasive demographic policy had arrested population growth and was delivering a huge demographic dividend. In the 1960s China had faced a run away population explosion. In 1965 the growth rate hit 2.8 percent per annum. The regime’s demographic policy brought that to an abrupt halt. The rate of natural increase (the difference between the crude birth and death rates) plunged to 1.2 percent. As a result, China had a demographic profile more like that of an industrialized country than a low-income country. Both its crude birth and death rates were like those of industrialized countries.

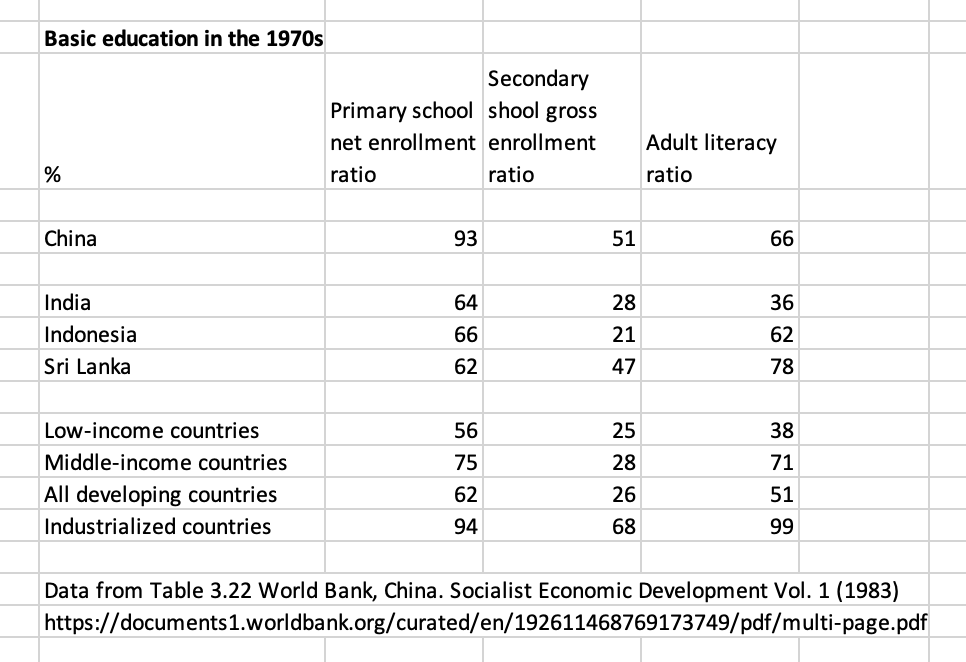

The basic logic of the demographic policy was to enable resources to be concentrated in educating children. By 1970s China’s advantage in terms of basic school education relative to other low income countries was already very striking.

All in all, the World Bank’s report was glowing. It is perhaps surprising, but in the heyday of neoliberalism, the World Bank, soon to become notorious as an agent of the Washington consensus, had little but praise not just for the new phase of reform, but for the legacy of the Maoist period. One might be tempted to dismiss this simply as kowtowing to an important new member state. Beijing would hardly react well to a more critical report. But there is every sign that the World Bank economists believed in their basic diagnosis. Indeed, they gave hostages to fortune with their predictive summary. Provided the right policies could be put in place, the World Bank was convinced on the basis of its findings in the early 1980s that China's "immense wealth of human talent, effort and discipline" would enable it "within a generation or so, to achieve a tremendous increase in the living standards of its people". If there was ever a prediction born out by history, this is it.

I wonder what the Chinese government's policy on gender equality was. Empowering women is often noted as an important factor in economic development.

For me, grounded academically in the political history of the momentous changes in China under the Maoist regime, this report and your analysis was doubly fascinating.